BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

21ST ANNUAL EDITION

3

in office by securing Strachan’s services for the

Memorial Chapel windows. On 10 October

1929 MacAlister suddenly announced that he

would retire five days later. Just one day before he

stepped down, the Chapel Committee authorised

Sir Donald to consult again with Strachan about

designing a complete scheme for the chapel

windows that could be implemented as funds

allowed. Unaware that MacAlister was no longer

in post, Strachan replied enthusiastically on 16

October 1929: ‘Ten years of constant demands

for windows far in excess of the number I could

undertake, may have robbed the letter post of

some of its earlier power to thrill in this way: but

the Complete Extensive Scheme with its superb

possibilities is a thing apart, and always sends the

blood to one’s head – pleasurably’. Thus began

an extraordinary commission that was to occupy

Strachan on and off until his death 21 years later.

Born in Aberdeen in 1875 and educated at

Robert Gordon’s, Strachan attended evening

classes at Gray’s School of Art while working

as an apprentice lithographer, then studied at

the Life School of the Royal Scottish Academy

in Edinburgh from 1894–5. After a stint as a

political cartoonist on the Manchester Evening

Chronicle in 1895–7, Strachan returned to

Aberdeen as a mural and portrait painter

before finding his passion for stained glass

in a commission for St Mary’s Chapel of the

historic Parish Kirk of St Nicholas. Among

other commissions in the city, Strachan also

worked for the University of Aberdeen at

King’s College Chapel and at the library of

Marischal College on the John Cruikshank

memorial windows, which celebrated the faculty

of science through the theme of creation.

By 1929 Strachan had gained an

international reputation through the publicity

surrounding his four huge windows of 1911–13

at the Peace Palace in The Hague. He also had

significant experience of designing complete

schemes, such as the Lowson Memorial Kirk in

Forfar of 1914–16, and war memorial windows

including those of 1923–7 for the Scottish

National War Memorial at Edinburgh Castle.

Although the university’s Hunterian

Museum and Art Gallery holds only one

preliminary design or ‘cartoon’ relating to the

chapel windows (the Alma Mater window),

the university archives contain an extensive

correspondence between Douglas Strachan

and Principal MacAlister and his successors,

Robert Rait from late October 1929 and

Hector Hetherington from 1936. These letters

are remarkable for the light they shed on

Strachan’s creative processes and the evolution

of an exceptional series of artistic works.

Strachan studied the chapel carefully

to capture its ‘personality’ and the ‘local

or community tang’, observing the light at

different times of day and noting various

practical bearings on the scheme so that the

new windows could ‘look as if they had grown

there naturally and inevitably’. Although

Principal MacAlister had initially suggested an

Old Testament theme based on Hebrews 11,

his successor Robert Rait was keen to allow

Strachan freedom to select the best treatment

for the space and not impose restrictions on his

artistic freedom. Eventually, after a period of

illness, Strachan sent a key plan with notes and

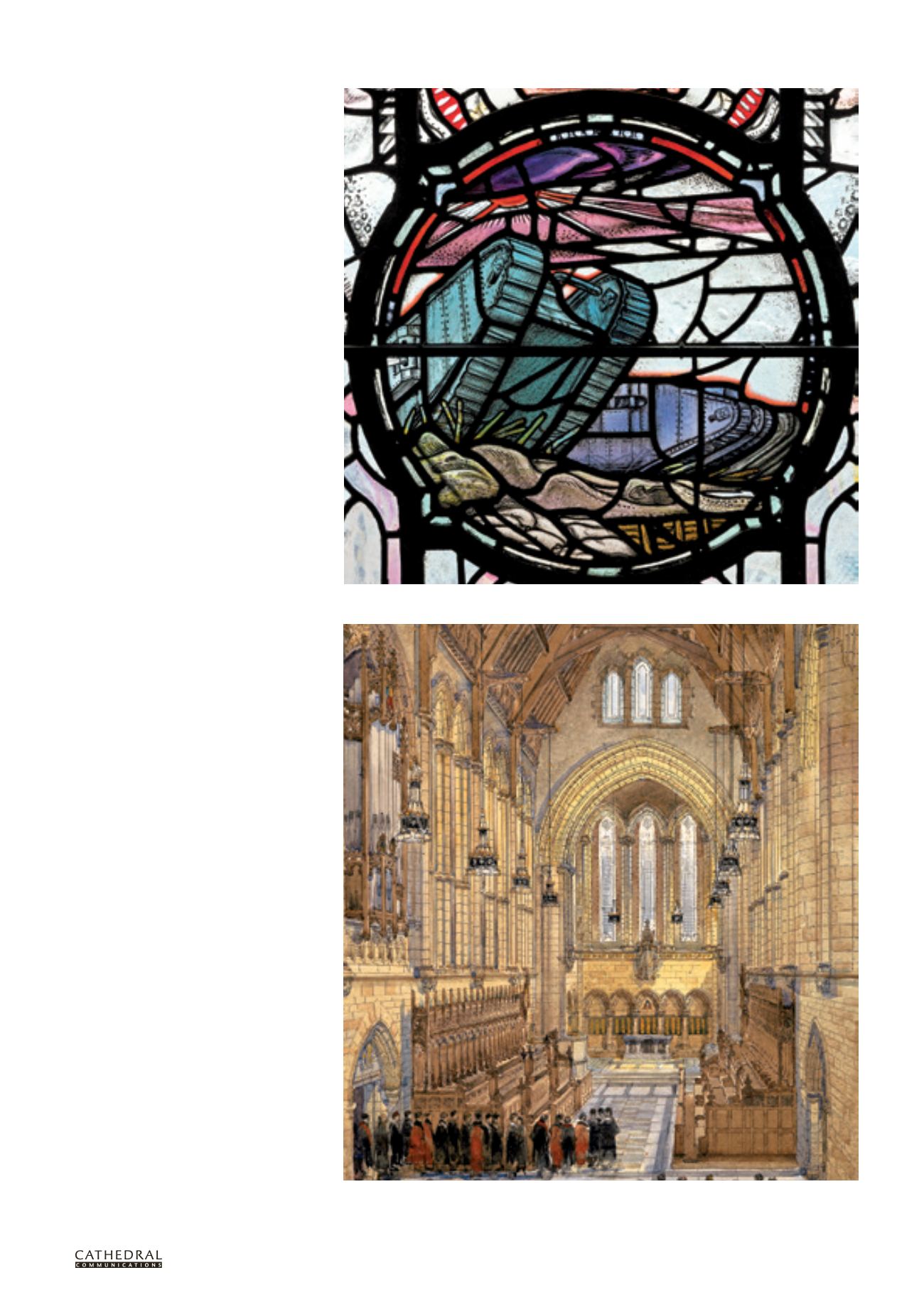

Detail of Strachan’s ‘Tanks, Machinery of War’ window at the Scottish National War Memorial, Edinburgh

(Photo: Antonia Reeve, reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of The Scottish National War Memorial)

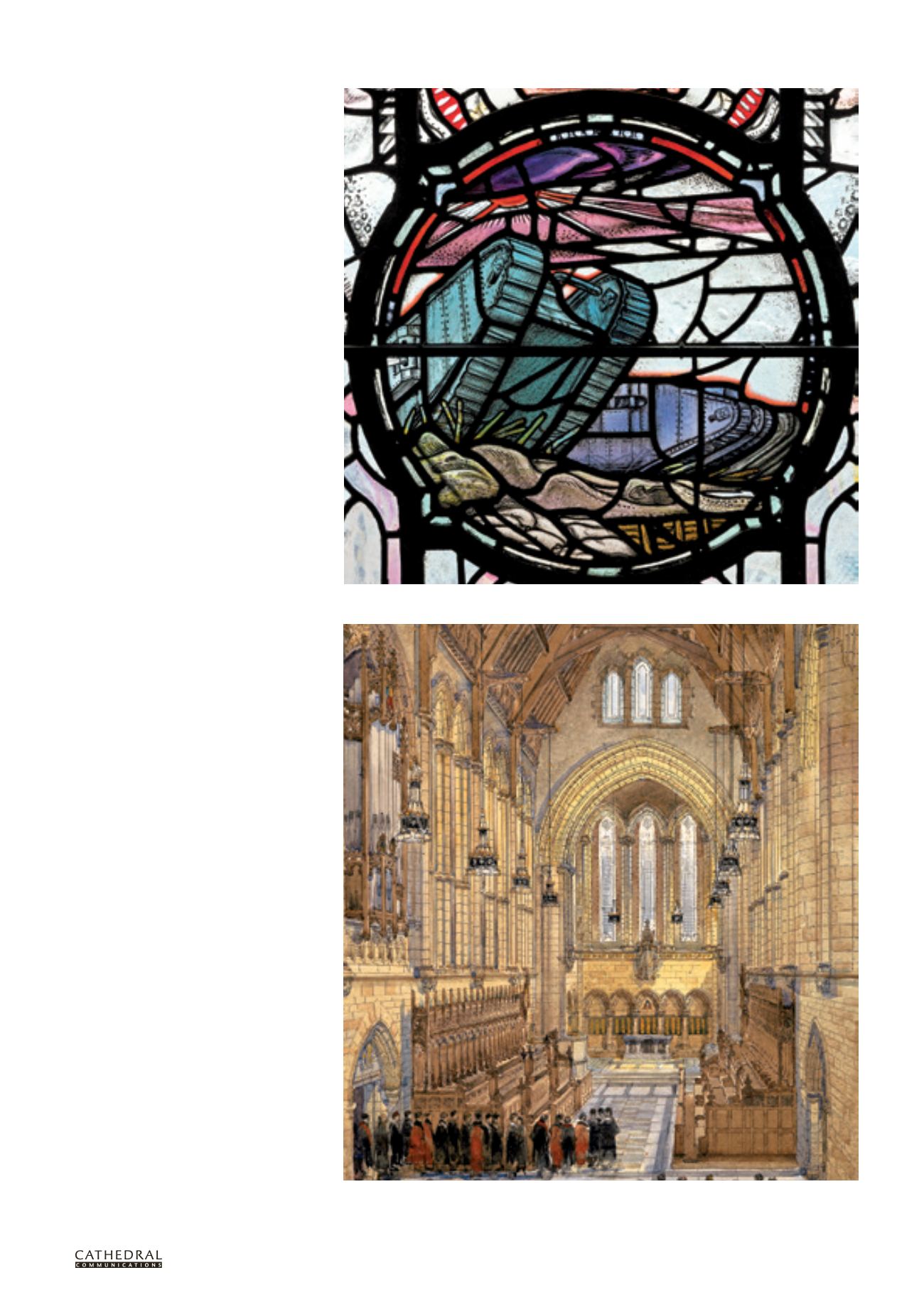

Design for the Memorial Chapel interior c1928, John Burnet, Son & Dick, watercolours added by Robert Eadie

(Reproduced by kind permission of the University of Glasgow)