BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

37

THE AYG YEW LISTS

Using the firm knowledge it has gathered,

the Ancient Yew Group has produced a

list of all the known significant yews in

Britain. Every yew on the list is considered

particularly worthy of careful protection

and is rated ‘ancient’, ‘veteran’ or simply

‘notable’. Just over 1,000 churchyards in

England contain AYG-listed yews, and

154 of them contain ancient specimens.

In Wales there are nearly 350 churchyards

with yews of note, and of these 84 contain

ancient trees. While the list of notable

yews remains a work in progress, the

group believes it has covered almost all

churchyards which have an ancient or

veteran yew, and the information for each

church and diocese is freely available on

the AYG website.

IS OUR YEW ANCIENT?

A simple means of assessment is to

measure the girth of the yew’s trunk at

its narrowest point. If it exceeds – or is

known in the past to have exceeded – five

metres in girth, the tree is likely to be

veteran. If the girth exceeds seven metres

then it is probably ancient. Sometimes it

can be demonstrated that smaller yews

are likely to be veteran or ancient. If you

have a large unlisted yew, please contact

the AYG via its website and a specialist

will come and assess it.

AGEING AND REGENERATION

As they progress through various life

stages old yews come to the attention

of those responsible for churchyard

maintenance. Some individual yews are

explored below exemplifying problems

and maintenance issues and solutions.

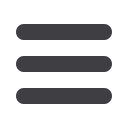

Among the yews which can be

considered for pre-Christian status is the

large yew in the churchyard at Tandridge,

first documented in

A Topographical

History of Surrey

by EW Brayley (1841): ‘At

the west end, is a large decayed yew-tree,

split into four or five parts, and in a state

of rapid decay. At five feet [1.5 metres]

from the ground, its circumference is

nearly thirty feet [9.1 metres]’.

Although reported to be in a state of

serious decay in 1841 the tree survived and

now flourishes as one of the best and most

spectacular specimens in the world. The

lesson of history is that very old yews can

regenerate satisfactorily, and seemingly

irreversible decay and destruction of parts

are incidents which, in the long-term, the

organism takes in its stride.

The Tandridge yew’s base

circumference was less than 10.5m when

recorded in 1890, and in the last 125

years it has increased during the flush

of regeneration by 53cm to nearly 11m.

This increase is likely to be faster than

the growth rate during the earlier period

of decay when girth increase may have

virtually stalled. The yew’s projected age

exceeds two millennia, placing the tree

in the illustrious company of yews at

Farringdon and Breamore in Hampshire,

the two Crowhursts in Sussex and Surrey,

Herstmonceaux in Sussex, Ashbrittle in

Somerset, Norbury in Shropshire, and

Llangernyw, Discoed and Bettws Newydd

in Wales among others.

The Tandridge yew’s successful

regeneration is very likely in large part

due to the canopy being allowed to grow

freely, and the fact that a fractured and

subsided trunk section was allowed

to grow out along the ground towards

the lych gate. Around the time of the

first world war when the tree had

considerably recovered, most of the

fallen trunk section was removed, but

two substantial layers were sensibly left

as by then it had established roots of its

own. The result is that we now have new

young trees that are genetically identical

with the original.

Here is a way forward in terms of

a philosophy of maintenance. Yews

have many survival mechanisms, and

sometimes what looks to human eyes

like a disaster may be one of these

mechanisms in progress. On the

whole, where there is no likelihood

of damage to persons or property

a yew should be left alone.

There are occasional exceptions,

however. At Long Sutton churchyard

in Hampshire a hollow ancient yew has

been effectively propped. The treatment

here is an excellent example of best

practice. The tree is so hollow that the

‘walls’ of the trunk are only barely capable

of supporting the re-growth of branch

material emanating from them and there

were occasional losses, as in 2000 when

a metre wide section of trunk fell when

overloaded by snow. Another fallen

section has long been allowed to lie in

situ, where it continues to grow.

A number of safe propping methods

exist, at Wilmington in Sussex telegraph

poles have been used to good effect, while

at Long Sutton the props are squared

timber with a footplate to prevent them

from sinking into the ground, and

rubber ties to prevent movement at the

join between the prop and the branch.

Propping should always be carried out

by a qualified arboriculturist. Although

trouble-free when done expertly, this

work has potential hazards, not least that

an incorrectly installed prop fails, causing

damage or injuring someone. The safety

of props needs regular review and an

arboriculturist’s plan should detail such

aftercare. From a procedural point of

view, proposals to prop a branch should

be treated as if the tree was to be cut and

a faculty is required.

The vast yew at Tandridge churchyard in Surrey

(All further photos: Toby Hindson)

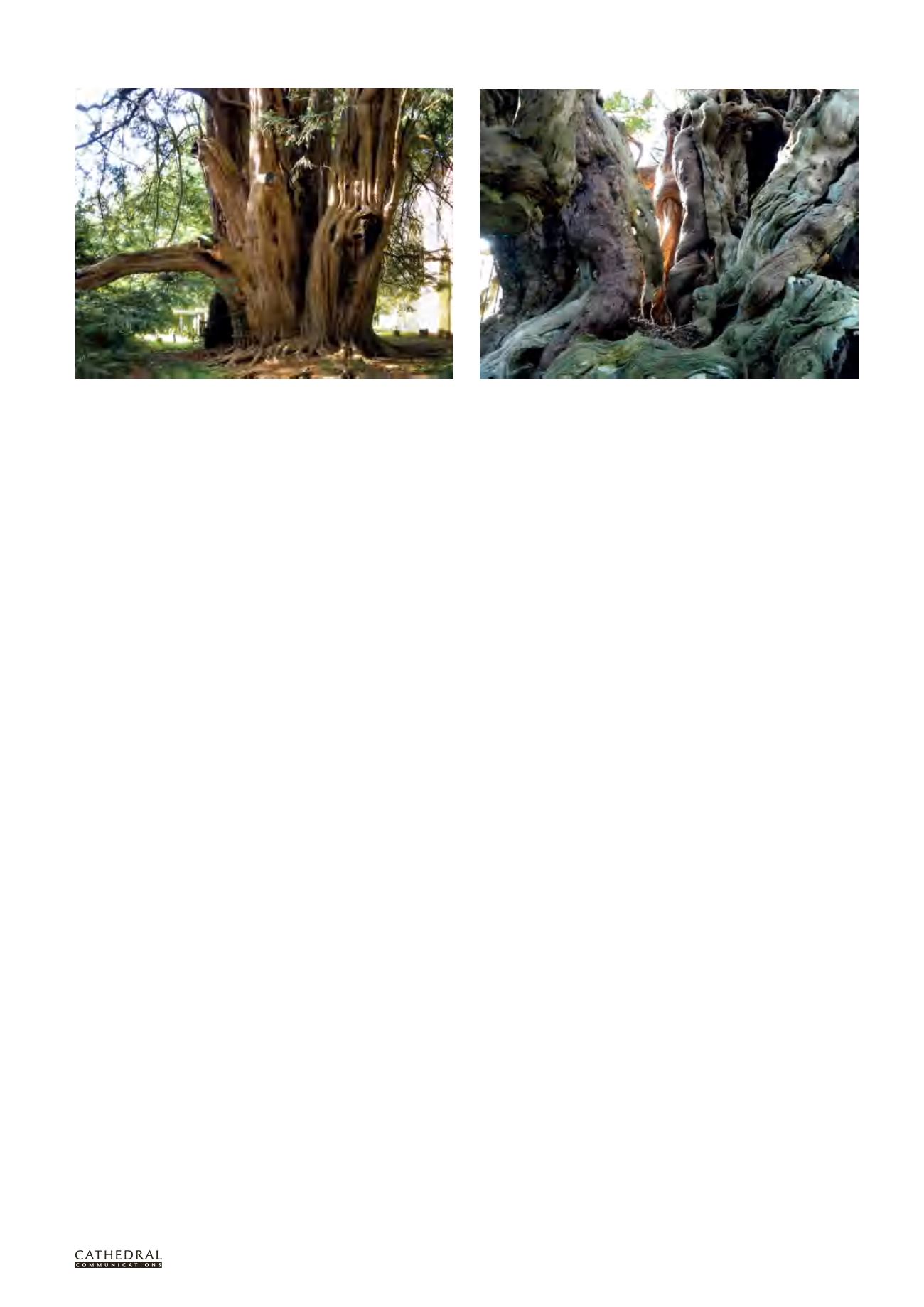

The extraordinary complexity of the Crowhurst yew in Sussex has developed over

two millennia or more, making the tree unique and irreplaceable