38

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

VANDALISM

Although inadvertent vandalism due

to ill-advised arboricultural practice

has been distressingly common in the

past, thankfully deliberate vandalism is

quite rare. Recent cases include a well-

documented ancient yew at St Mary’s

Church in Iffley, Oxon which has a

good claim to being contemporary with

the original Norman church. This tree

was completely stripped of the bark

on a major limb by local youths with

nothing better to do. The only course

in this instance is to remove the limb,

which cannot recover without bark,

and to instruct the local youths.

At St Mary’s Church in Linton,

Herefordshire a fire was set inside the

hollow of the vast and venerable yew.

Despite the ferocity of the blaze as the

inner wood burned, the tree narrowly

survived and now flourishes again,

another cautionary tale regarding the

inadvisability of removing damaged or

declining yews.

Nothing can stop vandals if they are

absolutely bent on destruction, but some

things can be done to reduce the risk of

this kind of damage. Twiggy lower trunk

growths are sharp and uninviting, mildly

dangerous and often removed to show

the shape of the trunk, but they do work

rather well as an anti-vandal ‘coating’, so

where the risk of vandal damage is present

keeping such twigs should be considered.

The churchyard of St George’s

Church in Crowhurst, Sussex boasts one

with salts over the active rooting area,

chopping the top of the tree off and

hoping it will regenerate… the list goes on.

Suffice it to say that humans with

poisons, chainsaws and plastics in

the recent past have represented the

biggest threat to these trees, some of

which have effectively looked after

themselves since they were planted by

Saxon or sometimes even older hands.

Work should never be undertaken on

an old yew without expert advice.

THE TOTTERIDGE YEW

At St Andrew’s Church in Totteridge

stands a very old ‘consecration yew’

of Saxon provenance, with a broad,

dead-looking trunk and a small bushy

canopy. The tree has a long history and

was first measured by Sir John Cullum

in 1677 at 26 feet in girth. Re-measures

through the years yielded the same result,

which remains the same to this day.

This represents a conundrum, because a

growth stall of over 300 years should have

killed it and the outer parts of the tree are

in fact dead.

The tree survives because it is

growing inside its old trunk: a mass of

strong and convoluted internal roots

which support most of the branches.

After three centuries like that the old

trunk looks set to fall away and expose

the new core that the tree has made for

itself, except for a number of narrow

runs of new vigorous wood which have

inexplicably managed to grow up the

old trunk surface like woody rivers.

The work of the churchwardens and

others associated with the churchyard

has been exemplary, the tree has been

suitably mulched to try to invigorate it

and nothing has been cut off it. It has

been able to regenerate in a fashion that

no-one could have predicted; an excellent

intervention for a temporarily somewhat

parlous Saxon yew, which has worked

very well. This incredible treasure was

spared removal and is responding to

gentle encouragement.

Further Information

The Ancient Yew Group

www.ancient-yew.orgTOBY HINDSON

is a working horticulturist

also engaged in long term empirical studies

of yew growth, and a founder member of the

Ancient Yew Group.

1

See Dr Charles Mynors’

‘Unauthorised Works’,

Historic Churches

2012

, Paragraph 8

(www.buildingconservation.com/articles/unauthorised-works/

unauthorised-works.htm)

PRINCIPLES OF CARE

•

Only carry out work which is clearly necessary

•

don’t let ivy grow up the tree

•

if work is needed, useful non-intrusive

interventions include weeding, fencing and

mulching

•

cutting or propping the tree must be left to

specialist qualified professionals;

British Standards (especially

BS3998:2010:

Tree work. Recommendations

) and Faculty

legislation apply

•

unauthorised works to trees covered by tree

protection orders or in churchyards which

fall within conservation areas may lead to

prosecution.

1

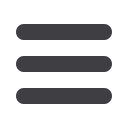

Plan of the ancient north yew at Long Sutton, Hampshire showing the use of props to support branches

of the oldest yews in England, probably

a pre-Christian tree. This specimen is

surrounded by an iron railing, as is the

huge yew at South Hayling in Hampshire.

Fencing is a good solution for reducing

footfall compaction of the rooting zone of

the yew and eliminating casual vandalism

but done properly it can be expensive.

IVY

Ivy is not generally a problem for yews

in the wild because the yew’s dense

canopy and surrounding vegetation tends

to shade it out. For yews managed by

humans, however, it is a different story.

Raised canopies and the clearing of

undergrowth allow more light to the base

of a yew, helping ivy to flourish.

Ivy is a stealthy killer of old yews,

once established in the canopy it will

reduce the vigour of the tree through

shading, and it can act like a sail, changing

the wind balance and weight of upright

sections which can lead to the tree being

wind-felled. Ivy may be a great habitat,

but if it is welcome in the churchyard

it should be allowed to colonise less

significant trees, not ancient yews.

ERRORS OF THE PAST

The greatest threat to historic yews

has been unenlightened management.

Damaging interventions include: felling

ancient specimens because they were

untidy or looked ‘ill’, filling hollow trunks

with everything from concrete through

foam filler to plastic bottles, weed killing

Railings have protected this very ancient yew at

Crowhurst in Sussex for over a century.

1

Section 3: living

fallen branch/section

Sections 2, 4

&

5: trunk and

associated branches supported

Section 6: timber lost in

1999/2000

Section 1: dead, too low to prop –

will eventually be lost entirely

Prop

Prop

Prop

North

3

2 1

4

5

6