1 0 2

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

MASONRY

moulds, allowed to air dry, then fired.In the

Tudor period purpose-built kilns were too

small for the vast number of bricks required

for the large, prestigious buildings then being

constructed in brick. So, bricks were usually

fired in simple wood-fired ‘clamps’, with the

bricks stacked around fire tunnels and the

whole structure daubed in clay or covered

with turfs. Firing took several days and the

clamps were then allowed to cool slowly.

Temperatures in the clamp varied,

affecting the degree of vitrification – the

fusion of silicate particles which occurs when

making ceramics or glass. In ideal conditions

the degree of vitrification would be sufficient

to form a well-bound matrix. Over-firing

could lead to excessive vitrification in the

bricks closest to the heat, causing them to

slump, while under-firing could result in some

being too soft for external use.

The nature of local brickmaking in

clamps made brick quality less reliable

than that of later mass-produced bricks,

and slight variations in size and shape

required Tudor builders to use deep joints

to accommodate the irregularities. In this

way they were able to take the use of bricks

to new heights with great palaces such

as Hampton Court, Lambeth Palace and

Oxburgh Hall. Brick became an exciting

medium which allowed a new and dynamic

evolution in design and embellishment.

Some of the finest historic brickwork

is demonstrated in 15th-century chimney

building, first in larger buildings but later

in simpler vernacular buildings too. Timber

and plaster fire hoods and smoke bays, which

caught fire very easily, were replaced by

purpose-built chimney breasts and stacks

in brick or stone. Early examples were often

added as external projections. In areas where

good building stone was plentiful, brick was

often preferred for chimneys for its ability to

resist heat.

While stone was used throughout the

country especially for large and high status

buildings, domestic building in in much of

southern England was still very much geared

to timber framed buildings. However, after the

Great Fire of London in 1666 a ban on timber

buildings in the city promoted the use of more

fire-resistant materials and bricks came into

regular use. Aided by a growing shortage of

timber for building, attitudes to brick began to

change, first in the capital and then beyond.

Bell Hall at Naburn near York epitomises

the growing trend for building in brick in

England in the late-17th century. Built on a

stone undercroft, this Grade I listed house is a

striking gentleman’s residence which was built

for the then MP of York, Sir John Hewley in

1680. He had no doubt seen good brick houses

in London and went to Hull to find builders

in brick for this house. By then the quality

of production had improved substantially,

resulting in more uniform dimensions and

allowing thinner joints to be used. An indent

or ‘frog’ was introduced, primarily to improve

the moulding of the clay, but it also had a

secondary effect of very much improving the

grip of the mortar to the brick .

Regulations to control brick sizes were

introduced during the 18th and 19th centuries,

but the big changes came with an improvement

in quality in late Georgian times, perhaps

as a result of canal building and the need

for stronger bricks for engineering work. In

the industrial revolution that followed, the

massive movement of people from country

to towns and cities spurred vast building

programmes. Without this step-change in brick

manufacturing it is uncertain whether towns

would have been able to expand so quickly.

By then clamp firing was less common,

with the major brick manufacturers producing

large numbers of bricks in down-draft kilns,

with the bricks separated from the burning

fuel by a low perimeter wall. This resulted in a

product of more uniform quality and colour.

Production became more efficient

following the introduction of continuous firing

kilns in the mid-19th century, such as the

Hoffman kiln, Firing occurred in successive

chambers in rotation, with the heat from one

firing being used to preheat the next one. The

development coincided with the removal of a

brick tax which had been introduced almost

100 years earlier to help pay for the wars in

America, as well as rapid expansion in the

railway network. The use of brick proliferated.

The colour of brick is primarily a product

of the clay used and the amount of air allowed

into the clamp or kiln during firing. A brick

that appears red on the surface may have

a core of yellow or deep grey where little

oxidisation has occurred, and the colour

varies across the face too, as a result of the

movement of air in the kiln or clamp and the

way the bricks were stacked.

Regional variations range from pale buff

yellow in the South East, such as London’s

stock bricks, to the bright reds found from the

West Midlands to the great northern cities of

Liverpool and Manchester, such as Accrington

Nori bricks. ‘Staffordshire blue bricks’, on the

other hand, are almost black due to a firing

process which achieved high temperatures

and oxygen deficiency, reducing the iron

oxides that would otherwise have coloured the

bricks. Performance and density varies too.

Staffordshire blues, for example, are strong

and densely made and were favoured for

engineering works.

CONSTRUCTION

Before repairs are designed, it is essential to

develop an understanding of the building’s

construction or how the element that is failing

or causing problems was made.

From the beginning of their use in late

and post-medieval times, bricks were laid in

lime mortar, which is relatively soft and highly

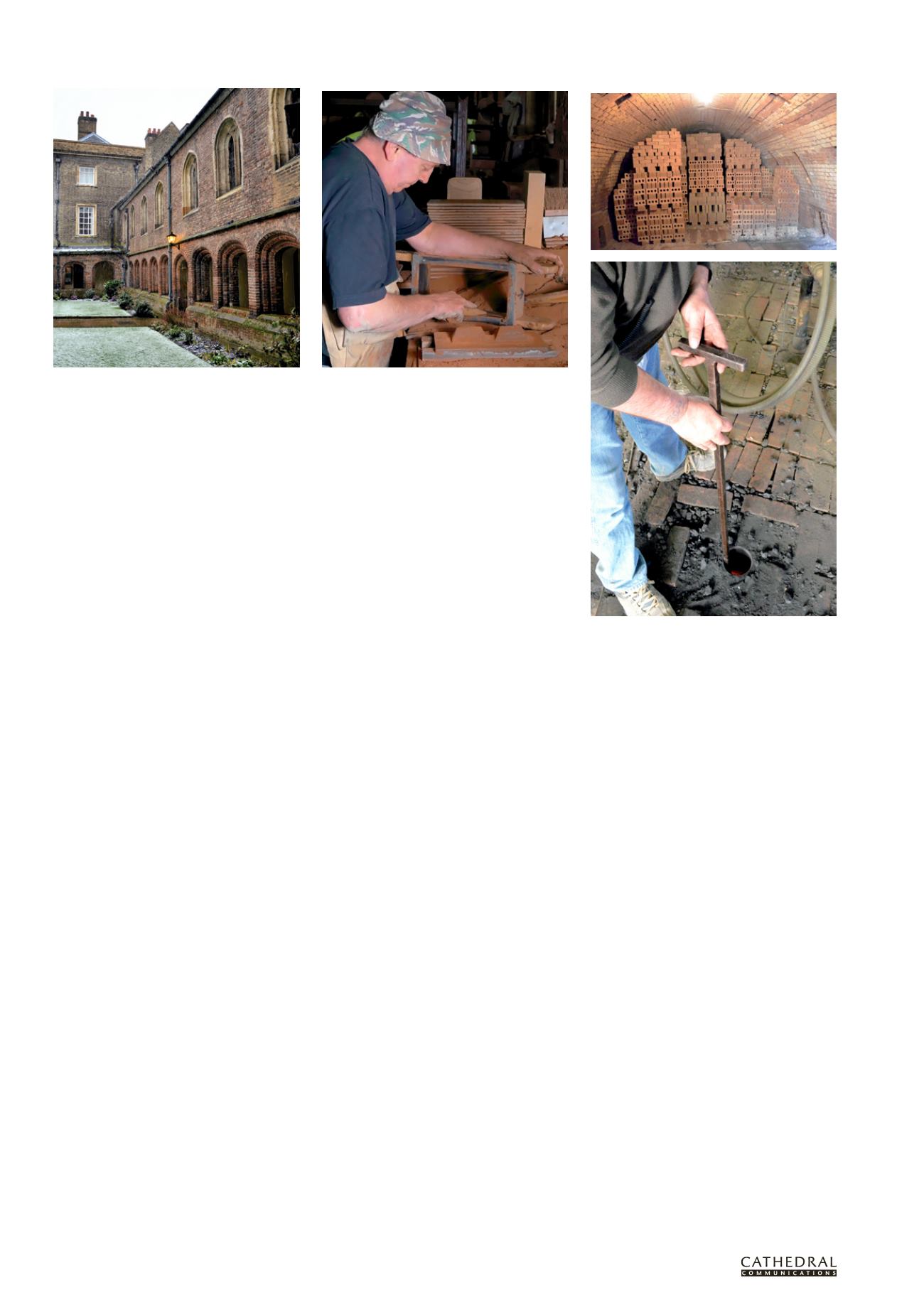

Tudor brickwork in the cloisters at Queens’ College,

Cambridge

A chamber in a continuous firing kiln at Northcot

Brick, now fired using gas and a small quantity

of coal to replicate the effects of late 19th century

technology. Firing progress is checked by inserting

a rod through a firing hole above the chamber to

measure variations in the size of the stacked bricks.

Brick making at Coleford Brick and Tile: the mould

for the frog can be seen fixed to the bench, and the

wooden stock (here being cleaned) is then placed over

it and filled with clay