T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

1 0 3

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

MASONRY

porous. Originally it was probably made from

lime putty mixed with coarse sand and other

aggregates, but in many parts of the country

the lime was impure enough to be more

‘hydraulic’ in nature.

Lime mortar remained in use until the

beginning of the 20th century. Whether

hydraulic or not, these traditional lime

mortars allowed some movement in the

brickwork without showing signs of cracking

under normal seasonal conditions.

Solid brick walls in domestic two-storey

buildings tend to be 9–13½ inches thick, which

equates to a depth of 1–1½ brick lengths. In

taller buildings base brickwork might be

18 inches thick or more, reducing in thickness

as you rise up the building. In the absence of

a cavity, solid walls simply rely on the mass

of the wall to keep moisture out, a principle

that works well as long as the wall is kept in

good condition. Rain would soak part way

into the structure but would then evaporate

away again. Walls constructed of porous brick

and lime mortar and which are plastered with

lime plasters are said to be ‘breathable’, as are

brick or flag floors. In the winter months, the

combination of large open fires and draughts

from ill-fitting windows and doors kept a flow

of warmed air running through a building

and so enhanced the evaporation of moisture

from walls and floors. The end result was a dry

building with little sign of damp internally. It

worked well, particularly when you consider

that damp-proof courses in wall bases and

under-floor membranes were only common

from the mid-19th century.

The brick bond, seen in the wall as its

horizontal pattern, can help in identifying

the construction of the wall. In a solid brick

wall of two leaves, header bricks are those laid

at right angles to the face of the wall to bond

inner and outer leaves, while stretchers are

those laid parallel with the face. In English

bond the courses alternate between headers

and stretchers. In English garden wall bond,

every fourth course or so is of headers, while

in Flemish bond stretchers and headers

alternate in the same course, and there are

many variations on these themes. The type of

bond used was often a trade-off between cost

and strength.

The appearance of header bricks can help

to distinguish solid brickwork from cavity

walls, which first began to appear in the mid-

19th century and became common in the early

20th. The outer leaf of the cavity wall is often

a half-brick thick, so it cannot have headers.

However, cavity walls of 15 or 15½ inches are

quite common, and look for all the world as

though they are solid. These can have a 9 inch

outer skin and an inner skin of 4½ inches

separated by a two-inch cavity. Some early

examples of cavity construction in the mid- to

late-19th century also used specially made

bricks, not iron wall ties, to join the two leaves

together, which appear as headers in the facade.

Just to make life even more difficult,

Flemish bond brickwork is sometimes found

where ‘snapped headers’ have been used. These

are half-length bricks rather than full length,

allowing a 4½ inch outer leaf to masquerade

as a solid wall. Snapped headers were also

sometimes used in solid walls, leaving the

outer skin poorly tied into its inner leaf.

Buildings can also deliver unexpected

problems. Larger buildings and terraces from

the late-17th to the mid-18th century saw some

poor building practices. Sometimes a high

quality brick outer skin was built by a different

team from the rest of the structure and was

inadequately tied into a poorer quality inner

skin. Despite the evident thickness of the wall

and the appearance of well-bonded brickwork,

the outer leaf is liable to move outwards

away from the inner. Frequently, wall plates

and so roof weights were supported off this

poor quality inner leaf. Such problems can be

expensive to put right.

The best bricks tended to be used for the

front of a building but as you move towards the

back, more often ‘commons’ or ‘stocks’ were

used, which were cheaper but not as regular

in shape. Internal bricks were usually of the

poorest quality and often under-fired as they

did not have to withstand the elements.

In the north of England there are tens of

thousands of houses with 9-inch thick walls,

usually at the rear, constructed with common

brick in English garden wall bond. These walls

were cheap to build, with header bricks every

five to seven courses to hold the wall together,

and the stretcher courses were not always fully

mortared. They must therefore be kept well

pointed to reduce the risk of water ingress.

In addition to solid wall construction,

an early use of brick was for infilling timber

frames. In houses, the frame and infill was

usually plastered on the inside and sometimes

rendered on the outside too, to draught-

proof the construction. Thinner walls in old

buildings, say 8 inches thick, that feel solid

when tapped, might well indicate a brick

infill to a timber frame. The thickness here is

controlled by the size of the timber posts and

beams used in construction, which remain

structural in performance.

In view of the wide variety of brick

construction methods, once the wall thickness

has been measured and the brick bond

inspected for clues to its construction, try

to get a view into the core of the wall from

around window reveals, or perhaps where a

gas meter has been built into an outer wall.

Only when you have fully understood what

you are dealing with can you start to consider

an appropriate repair.

BRICKWORK PROBLEMS

Problems with brickwork can be categorised as:

• inherent defects such as inadequate

firing, poor design or bad craftsmanship

• aging defects such as weathering

and settlement

• maintenance defects such as open

joints, plant growth in masonry and

saturation from leaking gutters.

Water plays a significant part in many of the

most common problems found in brick walls.

All brick is porous to some degree. Where

brickwork is well pointed, most rainwater is

shed from the relatively uniform surface, and

any moisture absorbed by the brick or the

mortar quickly evaporates. However, leaking

gutters and downspouts can lead to saturation,

causing major problems with any wall, brick

or otherwise. Constant water running down

walls will soak through most thicknesses of

brick wall, eventually leading to the decay

of any timbers it supports. Dry brick acts as

insulation, but saturated brick conducts heat,

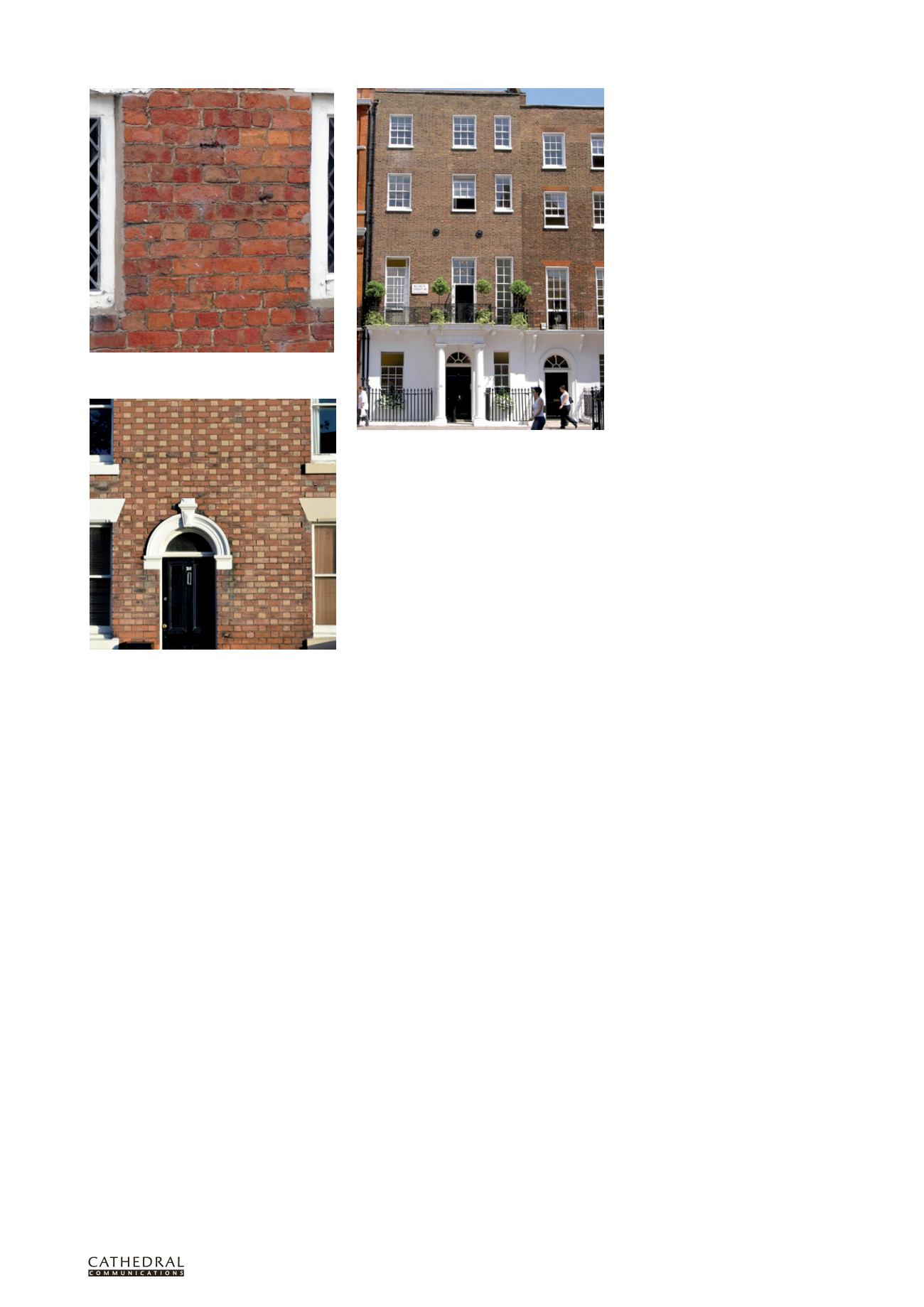

Detail of late 18th century English bond brickwork

with five courses of stretchers between header courses

Late 18th century terraced houses in Welbeck Street,

London: the ground floor and basement are stucco-

rendered, while the brickwork above is London stock

in Flemish bond.

Detail of late 19th century Flemish bond brickwork in

St Michael’s Street, Shrewsbury, with light-coloured

headers used to decorative effect