1 4

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

1

PROFESS IONAL SERV I CES

Historic England (the new name for the

protection arm of English Heritage), Cadw,

Historic Scotland and the Department of

the Environment – the statutory advisors

in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern

Ireland respectively – provide additional

guidance. The various national amenity

societies are also statutory consultees.

CONSERVATION STATEMENTS

AND MANAGEMENT PLANS

Conservation management plans first became

popular in Australia, where they were

developed by the National Trust for New

South Wales in 1982 in response to the Burra

Charter (see Recommended Reading entries

for James Semple Kerr and Kate Clark).

However, they did not become common in

the UK until 1996 when the Heritage Lottery

Fund made them a requirement of lottery

grant aid.

Conservation management plans are a

very useful tool for sustaining and managing

heritage assets. Indeed they ought to be

the starting point for the management

of any complex historic site, building or

landscape. The holistic approach to different

types of significance embedded in these

documents is particularly suited to large

sites with multiple management challenges

and opportunities, and various aspects of

cultural importance. They provide owners

and decision-makers with a balanced

framework which summarises the context,

including both practical issues and heritage

aspects, and contains policies to safely steer

owners, managers and developers away

from the temptation of convenience at the

expense of the heritage values (see Glossary)

that contribute to the site’s significance.

Following a description of the heritage

asset and what is known about its origins,

history and management, the heart

of these documents is the assessment

of significance and the agreement of

conservation management policies

to ensure that this is not diminished

through the process of future change.

Conservation statements also follow this

significance-driven approach and can be a

cost-effective solution for less complicated

sites or where there are no major development

proposals. Unlike conservation management

plans, conservation statements only briefly

consider the current challenges affecting

significance and the potential opportunities

at a site. Moreover, they rarely include

the detailed formulation of conservation

management policies that provide the

conservation framework. They can therefore

allow for a greater degree of flexibility when

considering future options, as rigorous

conservation management policies are neither

appropriate nor especially useful for buildings

where future uses are uncertain. Rigid policies

may result in limitations that would severely

hinder design creativity and options for viable

reuse and stifle potential solutions.

As a management tool, both conservation

management plans and conservation

statements are living documents that should

be revisited as required. It is particularly

important that they are updated following the

implementation of any development proposals

to ensure that they remain relevant, accurate

and effective.

Often the most successful major projects

are those where a conservation management

plan is commissioned at the outset, providing

the strategic background understanding of a

place before informing forward planning and

master planning exercises. One commonly

encountered pitfall occurs when conservation

management plans are commissioned too late

in the process and are expected to meekly

support projects that may be unsuitable.

Another problem is that conservation

statements and management plans are often

seen as one-off documents and do not form

part of the sustainable management strategy

of a site.

Two recent conservation management

plans serve to illustrate the range of challenges

and opportunities presented by different sites.

The late 17th-century Acklam Hall (Grade I)

is set in designed parkland that includes a

scheduled medieval fishpond. The occupant,

Middlesbrough College, was intending to

relocate and the report was prepared to guide

the owners, Middlesbrough Council, with

respect to the future development of the hall

and parkland.

In comparison, at the 19th-century

Ripon Workhouse Museum (Grade II) the

report focussed on the architectural and

social significance of the site, which had

been occupied by a poorhouse since 1776.

Of particular interest are the 1874 vagrants’

cellblock and dormitory. The conservation

management plan identified issues that have

the potential to determine the way in which

the site is managed and the plan provided

invaluable information for the museum’s

extension into additional buildings that were

previously part of the workhouse.

On a smaller scale, a conservation

statement at Lincoln Constitutional

(Conservative) Club guided proposals for

development of this vacant site, which had

fallen into very poor condition. Built in 1895,

this is a Grade II listed building in Lincoln’s

conservation area. It is now a successful

restaurant, bar, nightclub and events venue.

The most successful projects are those

that objectively consider the needs of a place

and engage the expertise and enthusiasm of

multiple stakeholder groups. This ensures

that local expertise informs the process and

that a consensus is achieved with dedicated

personnel, supportive of the plan, in place to

implement the recommendations and guide

change over the long term.

HERITAGE STATEMENTS

In contrast to conservation statements

and plans, which typically shape decisions

at an early stage, heritage statements

(also called heritage impact assessments)

respond to development proposals. They

incorporate a brief summary of a site’s

historical development and a description of

its current character, state of preservation

and significance and then assess the

likely impact of a proposed development

on the significance identified.

They are typically most effective when the

heritage specialists, conservation architects

or planners involved liaise closely with the

project architect and owner and provide

independent objective advice as early in the

process as possible and certainly before a

scheme is finalised on paper.

A heritage statement must be submitted

with any application for listed building

consent, scheduled monument consent or any

application for planning permission involving:

• designated heritage assets such as a

conservation area, world heritage site,

registered battlefield or registered

historic park and garden

• demolition or construction of a new

building within the curtilage of a listed

building or scheduled monument

• demolition of a non-

designated heritage asset

• known archaeological sites.

A well-prepared heritage statement can

make a substantial difference to the outcome

of a proposal. In the case of an electricity

sub-station at Arlington Road, London a

proposal to convert the building to provide

21 apartments was refused consent. The

building is located within, and makes a

positive contribution to, the Camden Town

Conservation Area. While the council

accepted the principle of residential use, it

was concerned about the impact of a roof-

top addition and the design of a prominent

rear elevation. A heritage statement was

subsequently prepared to assess the impact

of the proposal. On appeal, the inspector

concurred with this new evidence and

concluded that the proposal would preserve

the appearance and enhance the character of

the conservation area.

A heritage statement for St John’s

College, Durham formed part of successful

applications to secure planning permission

and listed building consent for the erection

of two accommodation blocks for students.

This sensitive site, which forms part of the

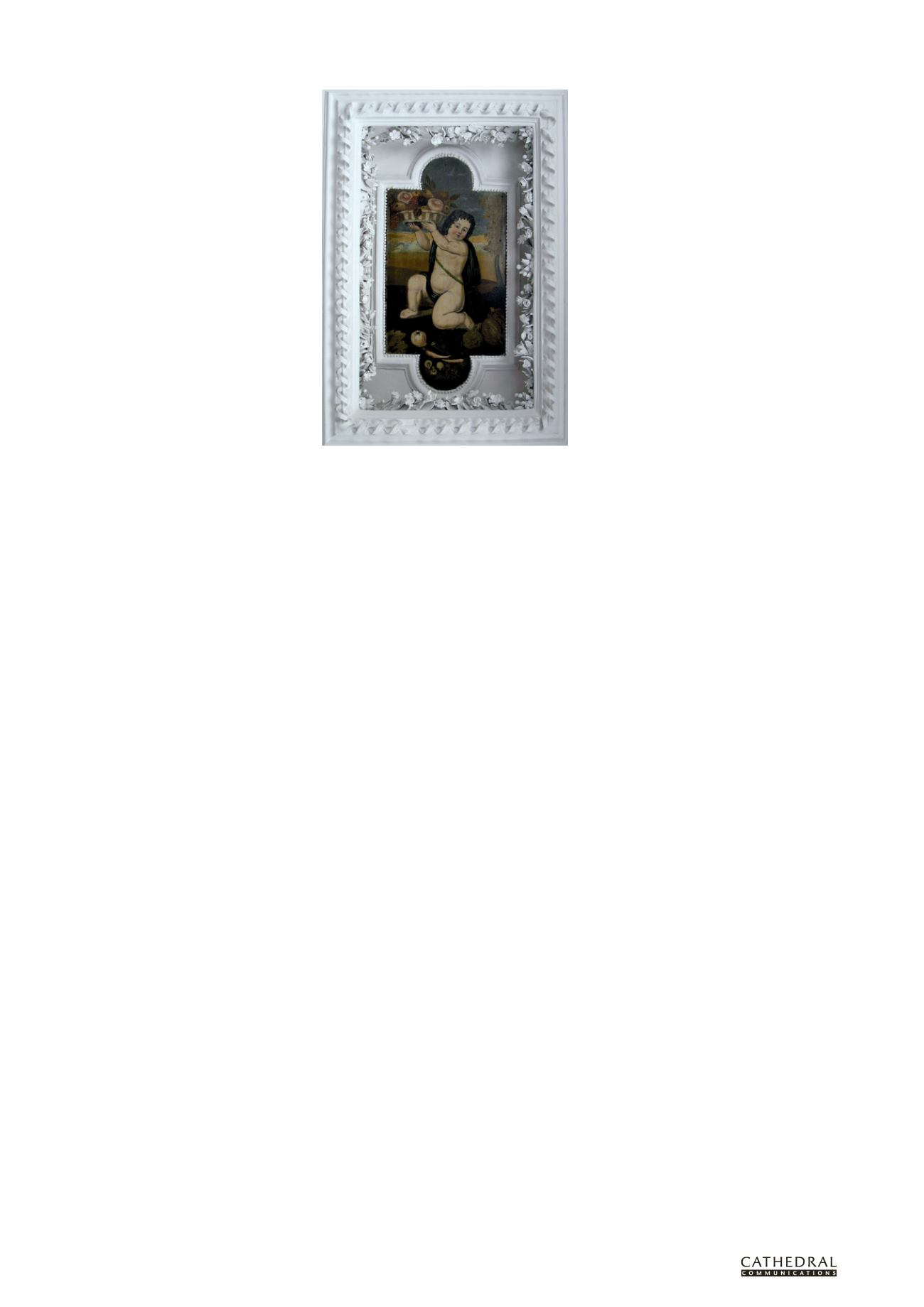

Elaborate plasterwork adorns ceilings at Acklam Hall