T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

4 3

1

PROFESS IONAL SERV I CES

although lightweight – typically 1–3kg

– they could do a great deal of damage

to a stained glass window. What might

seem to be easy to control and relatively

slow moving when flying in open air,

suddenly seems very much faster and

friskier when close to solid objects.

REGULATIONS

In the United Kingdom, the Civil Aviation

Authority is the regulatory authority for

all matters associated with non-military

aviation, including the operation of UAS.

Practice and regulation of small unmanned

aircraft has evolved out of the hobbyists’

use of radio-controlled model aircraft,

and remains reasonably simple and

straightforward, but as commercial use of

UAS increases, regulations and restrictions

are likely to become more stringent.

Essentially, the operator is fully

responsible for the safe operation of any

flight. In many circumstances a permission

(not a licence) from the CAA is required, for

example, if you intend to fly the UAS on a

commercial basis, or fly a camera/surveillance

fitted aircraft within congested areas, or close

to people or properties (vehicles, vessels or

structures) that are not under your control.

The CAA permission must be renewed

every 12 months and requires payment of a

modest fee depending on the weight of the

UAS. However, the ‘pilot’ does not need any

formal qualification (the Basic National UAS

Certificate for example) if the UAS is under

20kg and is flown in direct line of sight, within

500 metres horizontally and at a height not

exceeding 400 feet.

CAA permission is not required for

‘practice’ or demonstration flights, or if the

aircraft will not be flown close to people

or properties, and there is no ‘valuable

consideration’ (i.e. payment) for the flight.

Whatever the circumstance, anyone

contemplating any form of UAS flying

should familiarise themselves with the CAA

requirements (which are clearly defined

on their website), demonstrate adequate

competence as required and ensure that

they have adequate public and professional

liability insurance in place, and that they and

their insurers do actually understand the

competencies required and risks involved.

APPLICATIONS

At present, for the price of a good pair of

binoculars, a very capable ready-to-fly UAS

can reliably carry out detailed visual surveys

of inaccessible areas of buildings and other

structures. In a matter of minutes, detailed

images of high level stonework, inaccessible

metalwork such as weather vanes, chimney

stacks and concealed roofs and valley gutters

can be obtained. As always, it is far better if

the operator of the technology also has great

experience of surveying historic buildings,

so knows what to look for and where, and is

capable of identifying and analysing current

and potential faults. With instant FPV images

beamed back to the ground, this allows the

pilot/surveyor to concentrate in particular

detail on specific problem areas.

UAS aircraft can also be flown inside

large buildings, but this requires much

greater skill than flying outdoors. Proximity

sensors are now being developed that will

greatly reduce the risk of collision or damage.

Payload is always limited, but the aircraft

can carry very bright LED lights in addition

to cameras, which allows the detailed

visual survey of high vaulted roofs in large

churches and cathedrals, for example.

Aerial digital images from a UAS can be

integrated with terrestrial images of widely

different resolutions using currently available

software which can then process them to

produce 3D models of complex buildings such

as castles and cathedrals. Currently accuracy

is limited (typically 5mm to 20cm, across a

large and complex building, depending on the

system used) but should improve over time.

With any new technology, there is

often a rush of enthusiasm for its adoption.

It is quite possible for anyone to go out

and buy a £500 UAS and claim to be able

to survey your building. However, it is

most important that the operator is just

as fully experienced in interpreting and

diagnosing faults in historic buildings,

as they need to be in operating a UAS.

PREDICTIONS

As in the early stages of any new technology,

be it computers, mobile phones or indeed

manned aircraft, capabilities massively

and rapidly improve and real costs drop.

Predictions made in these early stages can

appear very wide of the mark only a short

time later, but UAS will almost certainly

become an accepted and common tool in

a specialist surveyor’s toolbox. Already, a

simple and palm-sized UAS aircraft, but still

with on-board camera, video recording and

a 100m range, can be bought for under £100

(thumb-sized and smaller are also available).

At the moment, a UAS can only inspect and

record, and further miniaturisation may not

offer much advantage, but greater control

and payload capacity might, for example,

allow accurate application of weed-killers to

inaccessible places.

What makes UAS technology particularly

interesting and difficult to predict is that

its emergence coincides with the arrival of

practical and relatively cheap 3D printers.

These two emergent technologies neatly fit

in with and greatly strengthen the worldwide

growth of the ‘Maker Movement’, with many

thousands of individuals around the world

openly sharing knowledge and skills. The

further development of UAS for civilian and

specific uses does not depend on military

funding or even big business.

At the current state of development,

compact and modestly priced UAS can reliably

provide detailed information that would

otherwise require the use of expensive and

time-consuming scaffolding, hydraulic access

platforms or specialist rope-access. A tall,

dangerous or inaccessible structure can be

surveyed very economically in a few minutes,

that might otherwise have taken many days

and cost thousands of pounds. It therefore

becomes economically viable to check

potential trouble spots such as inaccessible

valley and parapet gutters on a regular basis.

At the very least, a UAS survey should be

considered an essential element of every

quinquennial survey.

ROBERT DEMAUS

specialises in the non-

destructive assessment of buildings and

the detection and assessment of decay,

weakness and fire damage in structural

timber. He is a director of Demaus Building

Diagnostics Ltd

(see page 31)

.

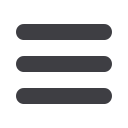

A typical compact (approximately 500mm wide)

four-rotor UAS carrying a GoPro video camera, as

used for the aerial survey of Boscobel House.

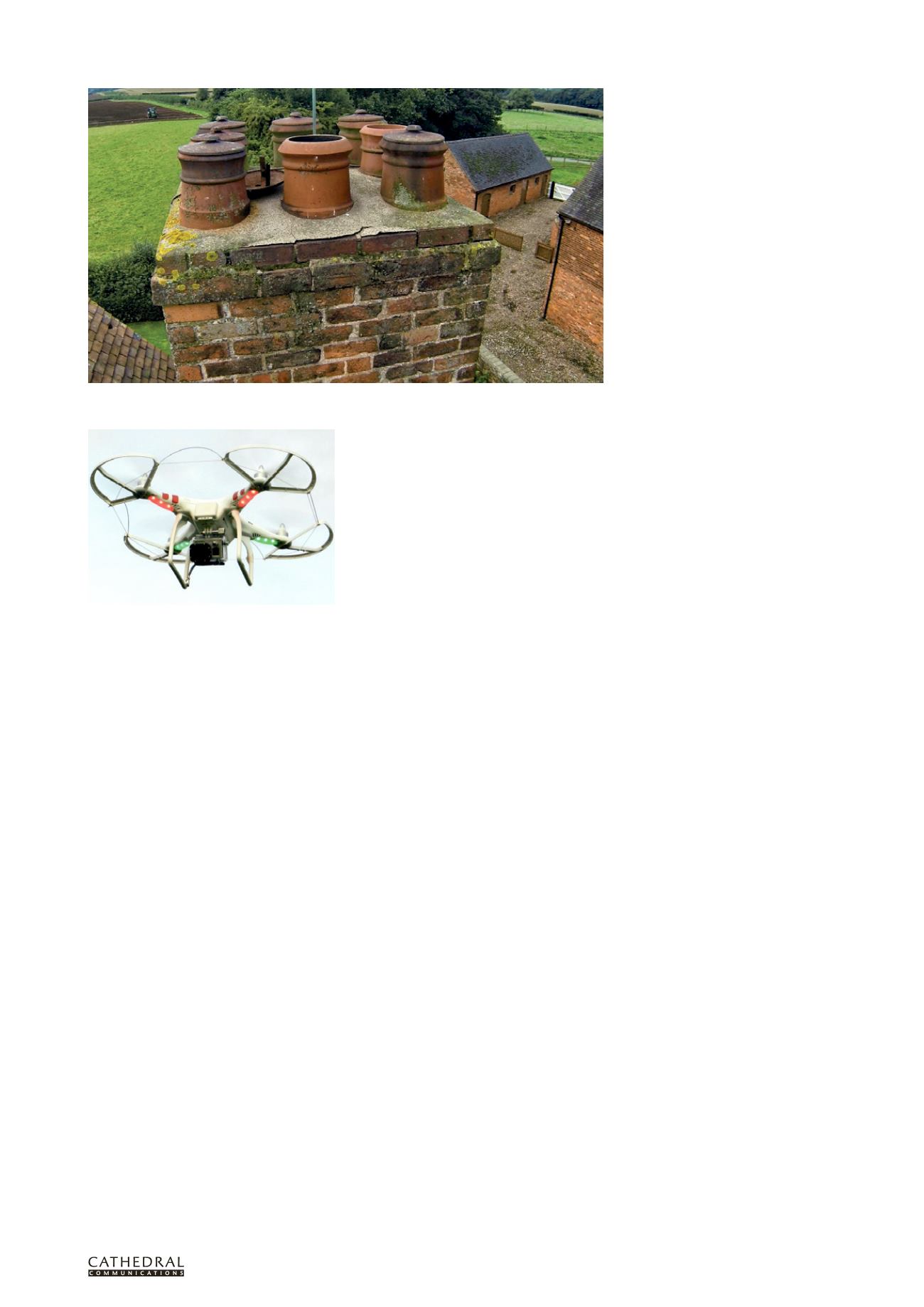

One of the chimneys at Boscobel: photos taken by UAS can quickly provide important information for a

quinquennial inspection and for programming maintenance