9 6

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

MASONRY

Advantages

• superior joint finish

• uniformity of colour and strength

• greater choice of joint finishes

• clean face work

Disadvantages

• increased labour and material costs

• additional construction time

• if incorrectly executed the

compound joint may fail to unite

• requires skilled and experienced pointers.

AIMS

There are two principal reasons for finishing

the external joints of brickwork:

Structural

Even when properly dampened

before laying or pointing, bricks absorb

moisture from the mortar. Along with

evaporation, this results in partial de-hydration

of the joint towards the joint face. So the action

of the jointing tool consolidates the surface

of the joints closing up shrinkage cracks and

protecting against the ingress of driving rain.

Aesthetic

Jointing or pointing, especially

the latter, when executed according to

the historic traditions of the craft, are

highly-skilled operations. Well jointed or

pointed brickwork will be uniformly and

precisely finished, no stains will mar the

facade and the finished joints will not be

obtrusive. The observer’s eye must never

be drawn to the joints but, rather, to the

overall brickwork and to features such

as arches and decorative mouldings.

Inadequate modern training means that

most bricklayers today lack knowledge of

traditional tools, equipment and materials,

and haven’t received the proper level of

practical tuition necessary to develop these

all-important skills, which at their highest

expression are an art. Their work often

involves the wrong mortars, including

those based on cement (ordinary Portland

cement). OPC, being hard, inflexible

and dense, is wholly inappropriate for

traditionally built brickwork in soft, flexible

and porous lime mortars and can cause

the bricks themselves to deteriorate. The

use of cement-rich mortars is generally

ill-timed, heavy-handed and neither true

in style or execution, all of which means

that many fine facades of historic brickwork

are marred or irreversibly ruined.

Colour washing

Until the 19th century,

when developments in kiln technology

produced bricks with a fairly uniform colour,

most premier facades were dyed using

natural earth pigments such as ochres to

regularise uneven brick tones. When brick

colours were largely orange to red this was

frequently referred to as ‘ochering’, ‘raddling’

or ‘ruddling’, but as buff-coloured bricks

became fashionable the term ‘colour washing’

was adopted. The term should not be confused

with lime washing: a colourwash does not

contain lime. Typically, the earth pigments are

mixed in small (weak) ale and/or glue size to

help it adhere. Alum (potassium aluminium

sulphate), or ‘white copperas’ (zinc sulphate)

is used as a mordant to ‘fix’ the pigment and

make it weatherproof.

Pencilling

If jointed, colour washing

results in the joints being coloured too,

so these were always picked-out again to

re-emphasise the bond, but always to a

lesser scale, through a craft practice called

pencilling. This was usually executed in white

distemper – a mix of crushed chalk (whiting

or whitening) and glue size, although black or

red pencilling is occasionally seen. Pencilling

was frequently applied free-hand with a thin

brush until the beginning of the 17th century.

Thereafter, during a period characterised by

refinement, the application of pencilling was

guided by a straight-edge, or rule.

As tastes changed and brick quality

improved, some designers preferred the

natural colours of hand-picked bricks for the

facades, so pencilling was sometimes applied

to joints on facades which were not colour

washed, resulting in just a thin white line in

the groove of the joints.

HISTORIC ENGLISH JOINT FINISHES

Flat joint

This is also termed ‘flush’ as the joint is

finished level to the brick faces. During the

17th and 18th centuries this was frequently

smoothed and after colour washing the

facade, joints were neatly pencilled, guided

by a rule. This work can be mistaken for tuck

pointing. Some designers used it during the

Arts & Crafts period, rubbing the suitably

stiffened surface of the joints with a hessian

sack to raise the aggregate and give a rustic

appearance that led to the name ‘bagged joint’.

The technique was derided by highly-skilled,

London pointers as the ‘Westminster Smear’.

Struck joint

The craft term for inclining a joint finish is

‘striking’. During the 15th century some joints

were crudely ‘struck’ when jointing with

the trowel by inclining the finish of the bed

joint in towards the upper arris of the lower

brick, so the lower edge was slightly recessed.

The technique developed as a way of hiding

variations in brick shapes: the top of each

course of bricks was carefully ‘lined-in’ by the

bricklayers, but the lower edge was irregular

as a result. Striking emphasised the straightest

edge and helped to hide the more uneven

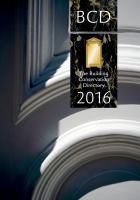

Some of the main historic joint profiles

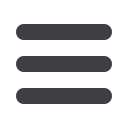

Pigmented black ‘weather-struck and cut’ pointing

(All images and examples on this page by the author)

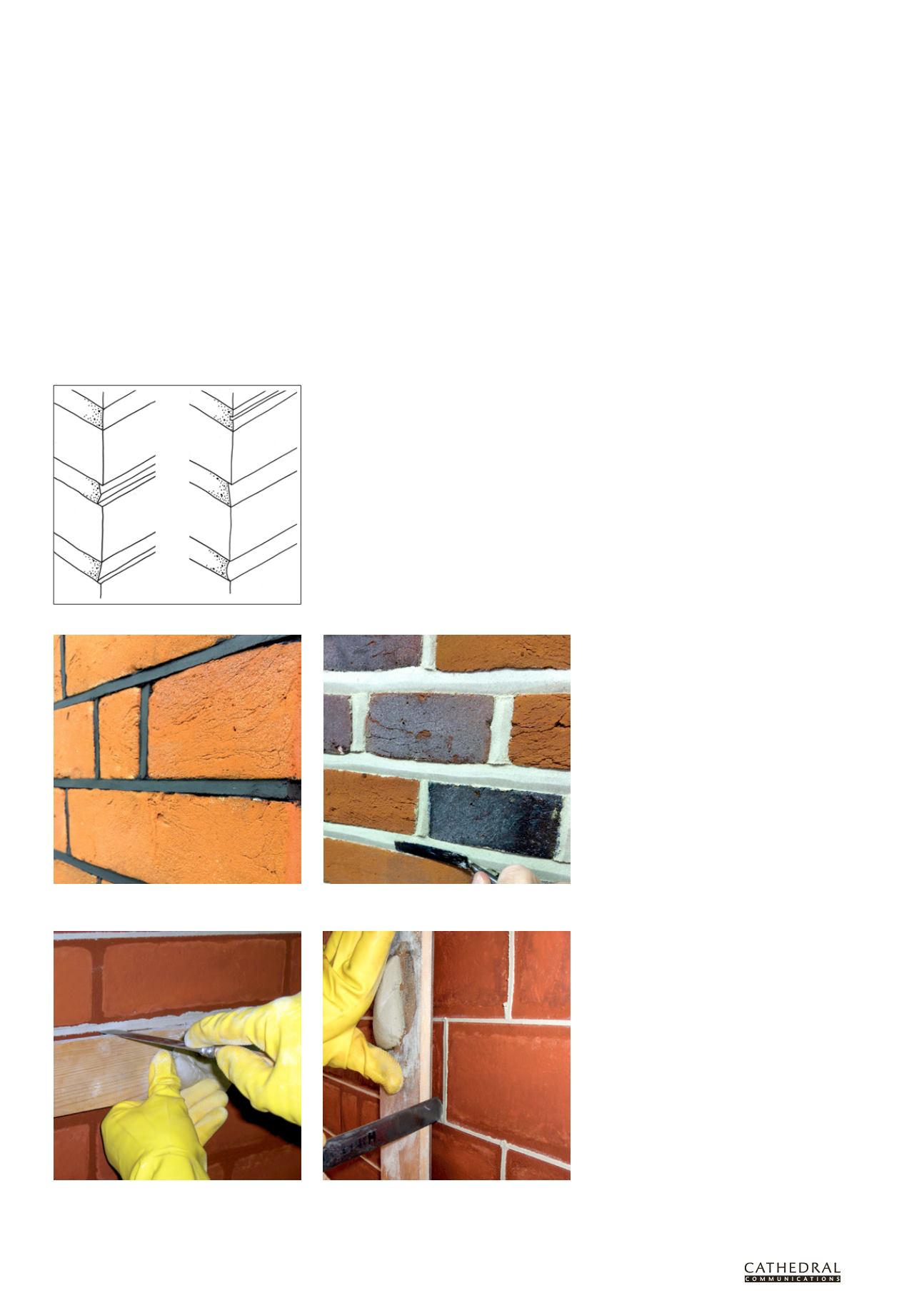

Applying a ‘double-struck’ profile to a bed joint

Using the adapted knife or ‘Frenchman’ to trim a bed

joint ribbon during tuck pointing

Using the adapted knife or ‘Frenchman’ to trim the

joint ribbon of a perpend during tuck pointing

Flush

Ruled

Double-

struck

Weather-

struck

Overhand-

struck

Keyed