T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

9 7

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

MASONRY

lower arrises. The perpends were also struck,

typically from right to left.

As brick quality improved, joints became

thinner and more regular in size. As a result

this joint became refined as either a jointed

or pointed finish. The joints were struck

and trimmed precisely with a jointer and an

adapted knife called a ‘Frenchman’, guided

by the pointing rule. If after being struck

the joints were then ruled this was called

‘struck and ruled’, or ‘joints jointed’. By the

19th century it began to be called ‘overhand-

struck’, because it was indicative of being

profiled by working overhand, or from the

inside the wall, and also to distinguish it from

the new, and increasingly popular, ‘weather-

struck’ joint profile which was recessed at the

top of the joint.

Double-struck joint

A jointed profile formed by drawing the trowel

along the mortar, just in from the arris of the

upper course of bricks and then reversing the

action by cutting in behind the arris of the

lower bricks to produce an approximate raised

centre line. It is seen from the 15th century

onwards and was often used on high-status

Tudor buildings such as Hampton Court

Palace. Here there is a 1522 example of red

colour-washed brickwork with pigmented

double-struck joints which have been

pencilled white on the lower half of all the bed

joints and to one side of the perpends. This

technique reduces the aesthetic impact of the

large joints by 50 per cent.

Ruled joint

This joint became popular during the early

17th century when the desire for a refined

appearance of line and verticality were

paramount. The profile was formed, after

the face of the joints had been either slightly

flattened or struck, by running a thin-bladed

jointer, guided by the pointing-rule, along

the centre of the beds and perpends to form a

groove, typically 2–3mm wide. Depending on

the shape of the edge of the blade the groove

could be squared or slightly rounded. During

the later 19th century some craftsmen used

the edge of an old penny to effect the groove,

leading to the name ‘penny-round’ or ‘penny-

struck’ joint. This was never achieved, as some

have suggested, by grooving with the tip of a

trowel, as that would simply slice the joints

and is aesthetically unsatisfactory.

Tuck pointing

Tuck pointing appeared in the late 17th

century when it was known as ‘tuck and pat’

work. Reserved for the premier facades of

standard brickwork and for ‘axed’ arches

(with tapered bricks), it was used to mimic

the aesthetics of finely jointed gauged work.

Executed properly, it remains the most highly-

skilled area of pointing.

A backing or ‘stopping’ mortar, coloured

to match the bricks, was applied to the bed

and perpends and finished flush to the bricks

and then set out with a grid of very thin

grooves. The grid established level and plumb,

and the groove helped to lock-in the centre of

the rear of the lime putty and silver sand mix

which was applied over them using a jointer

guided by a pointing rule or ‘feather edge’.

This was then trimmed top and bottom with

the Frenchman to form precisely sized narrow

ribbons. Although usually cream coloured,

black and occasionally red ribbons were also

used in the Victorian period.

As tuck pointing was used to create the

illusion of fine, accurately bonded brickwork,

the ribbons of mortar are often found to

have been applied across the faces of the

colour-washed bricks to create entirely

fictitious perpends, and sometimes to correct

discrepancies in courses too.

Bastard tuck

Less common, this profile is seen as a skilfully

executed jointed or pointed finish. A less

sophisticated version of tuck pointing, it was

used to create neatly finished ribbons. When

jointed this was achieved by carefully cutting

the bedding mortar with the Frenchman just

in from the arrises. When pointed, a neutral

stopping mortar would be applied, flushed

and grooved, with the same stopping mortar

laid on in the manner of true tuck pointing,

and trimmed to form ribbons. These ribbons

were also occasionally pencilled to finish and

emphasise them.

Weather-struck joint

Dating from the 19th century and most

common in civil engineering work, this profile

is formed by compressing the top portion of

the joint more than the lower, inclining the

blade of the trowel or jointer as the joint is

finished in a one-direction stroke. This causes

the upper edge of the joint to come slightly in

from the arrises of the upper bricks and flush

with the upper arrises of the lower bricks (and

never protruding). The perpends, which are

struck first, are sloped from left to right, to

angle it flush to the neighbouring brick.

When the trowel is used to form this

profile on the bedding mortar it is called

‘weathered jointing’. A superior pointed finish,

‘weather-struck and cut’, involves the profiled

joints being trimmed using a feather-edge and

the Frenchman. Traditional pointers did not

use trowels to strike the joint, instead using a

technique based on tuck pointing that created

a regular, accurate and subtle profile. When

executed in cement-rich mortar with heavy

profiling, this joint can be very ugly indeed.

CONSERVATION PHILOSOPHY

When repairing or conserving historic

brickwork it is easy to overlook the original

profile where worn and eroded, and many

buildings repointed in recent years have

now lost all trace of their original details.

The result has a dramatic impact on the

character of the original brickwork. Before any

repointing is carried out, it is most important

to carry out a thorough survey, carefully

examining sheltered areas for the original

profile and for traces of colour. Any variation

from the original aggregate, mix, profile and

colour should only be made where there is

clear evidence that the original would be

harmful to the surviving brickwork.

GERARD LYNCH

MA PhD is a master

brickmason, historic brickwork consultant

and author of several books on historic

brickwork – see

www.brickmaster.co.uk.

He trained through the apprenticeship

system and at Bedford College where he

later became head of trowel trades. He is

internationally recognised for his extensive

specialist knowledge and skills in the

conservation, repair and re-pointing of

traditional and historic brickwork.

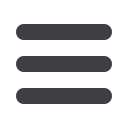

A thin-bladed jointer run along a bed joint, guided

by the levelled ‘pointing rule’, to create a ‘ruled’

joint. see

www.brickmaster.co.uk. (All images and

examples on this page by the author)

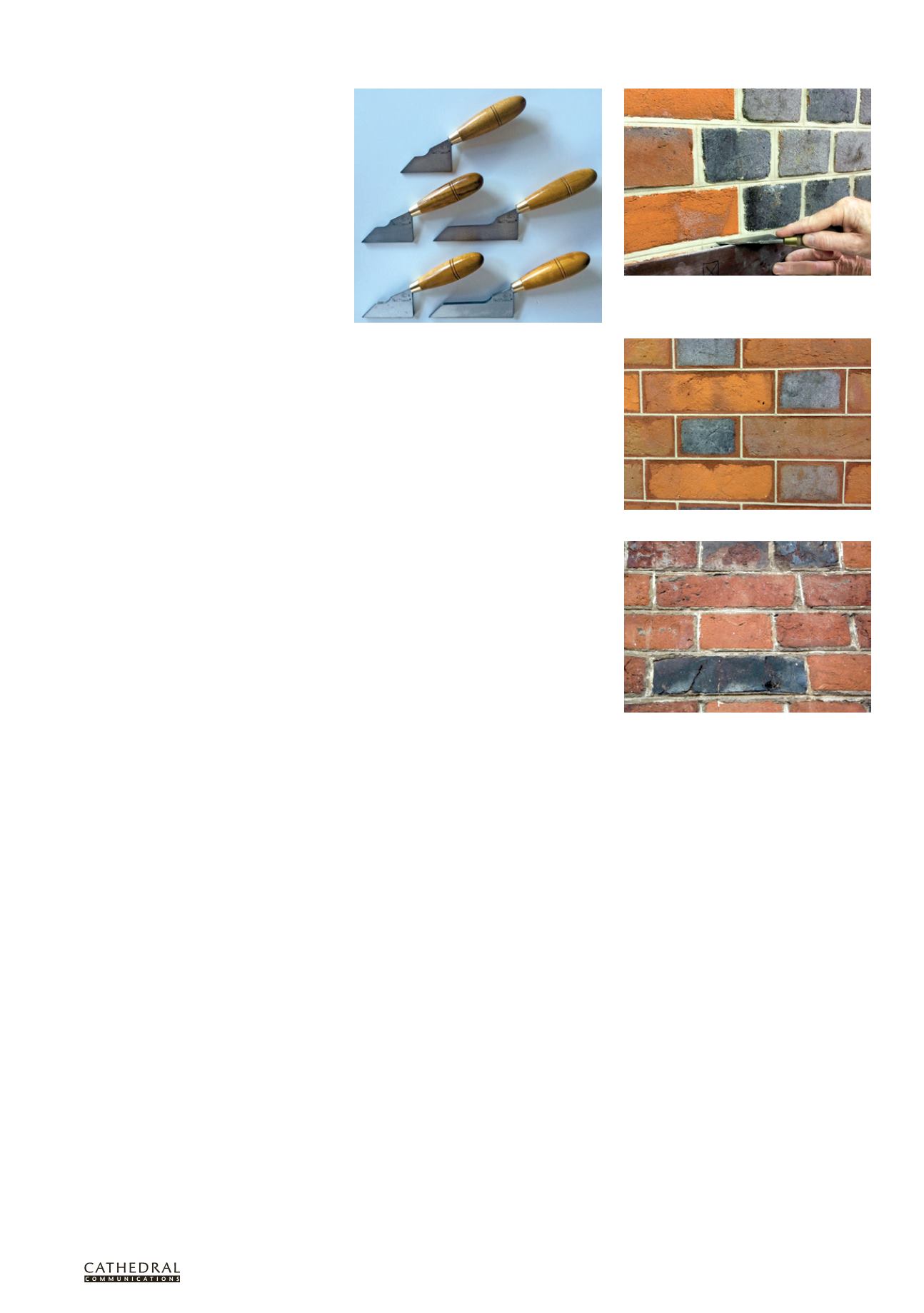

An example of fine and accurate tuck pointing

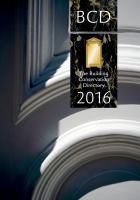

A selection of traditional-styled brick jointers

available from The Red Mason range

An example of early 18th century white coloured

‘pencilling’ applied over a ‘ruled’ joint in Woburn,

Bedfordshire