12

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

early 19th-century stopgaps were filled

with pieces of unpainted coloured

glass, an honest repair which was easily

distinguished but visually very disturbing.

The most aesthetically destructive

aspect of the restoration was the use

of thick (10–12mm) leads throughout

the window, darkening the panels and

disguising the delicate relationship

between glass and lead achieved by

Thornton and his collaborators.

Exploratory conservation trials

undertaken by the York Glaziers Trust

(YGT) between 2005 and 2008 reviewed

a number of conservation options,

ranging from a light overall clean, to

the dismantling and full conservation

of the panels, with the recovery of John

Thornton’s cutline as one of several

objectives. However, one over-riding

priority was to install state-of-the-art

ventilated protective (isothermal) glazing.

In step with the guidelines of the

International Corpus Vitrearum (see

Recommended Reading), no dismantling,

reordering or restoration could be

justified without thorough research. As

a result, the forensic examination and

recording of every piece of glass has been

complemented throughout the project by

in-depth exploration of the antiquarian

and art historical context of the window.

The discovery of drawings and

photographs dating from the 1730s,

1880s and c1939 has been essential to

understanding the restoration history of

the window. Above all, the meticulous

description compiled in the 1690s by

antiquary James Torre has not only

shed light on individual panels, but has

confirmed the original panel order of this

immense biblical narrative.

After long and detailed consultation

with the Cathedral Fabric Commission for

England and other statutory consultees,

the Minster decided to proceed with

the dismantling, conservation and

reglazing of the window. This process was

supported throughout by the guidance of

Chapter’s East Window Advisory Group.

After careful cleaning to remove

hygroscopic dirt, the dismantled glass

pieces were closely examined for evidence

of their original location in the panel.

Clues provided by edges which had been

‘grozed’ by the medieval glaziers (nibbled

away with a hooked tool to fit snugly

into the lead) were always invaluable

evidence of authenticity and relationship

to adjoining pieces. Also, indications of

glass structure, corrosion patterns and

traces of lost paint, observable through a

binocular microscope, often confirmed

the evidence of surviving painted detail,

allowing multi-fractured and heavily

corroded pieces to be reunited. Mending

leads in obtrusive or lightly coloured areas

have been removed whenever possible.

The epoxy resins Araldite 2020 and Hxtal

NYL-1 have both been used for edge-

bonding, depending on the condition of

the glass and the nature of the fracture.

Detailed criteria have been used

to determine whether later stopgaps

should be retained or removed, and

those removed from the window have

been recorded and retained as part

of the project archive. Every process

and decision has been meticulously

recorded and new methods of digital

documentation have been developed

specifically for this project.

PROTECTIVE GLAZING

From the outset the East Window

Advisory Group was clear in its

view that the provision of protective

glazing was the single most important

contribution that modern conservation

could make to the preservation of John

Thornton’s medieval masterpiece.

In 1861 the Great East Window was

provided with crude exterior glazing, first

in the form of single sheets of glass and

later by diamond panes or ‘quarries’. Two

new glazing grooves were cut into the

window mullions of the main lights. The

exterior glazing was mortared into the

outer groove. The original glazing position

was abandoned and the stained glass

was set into the new inner groove. The

window was effectively double-glazed,

with no ventilation between the outer

and inner glazing. Advances in protective

glazing design have demonstrated the

importance of ventilation and this project

provided the opportunity to significantly

improve the system.

The new protection of the Great

East Window will take advantage of the

additional exterior glazing groove, but

the system is governed by the principles

of modern isothermal protective glazing

(see diagram opposite). An interspace of

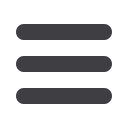

Panel 5b following incorrect restoration by Dean Milner-White, who inserted

a second beast in the centre of the panel constructed from miscellaneous

fragments

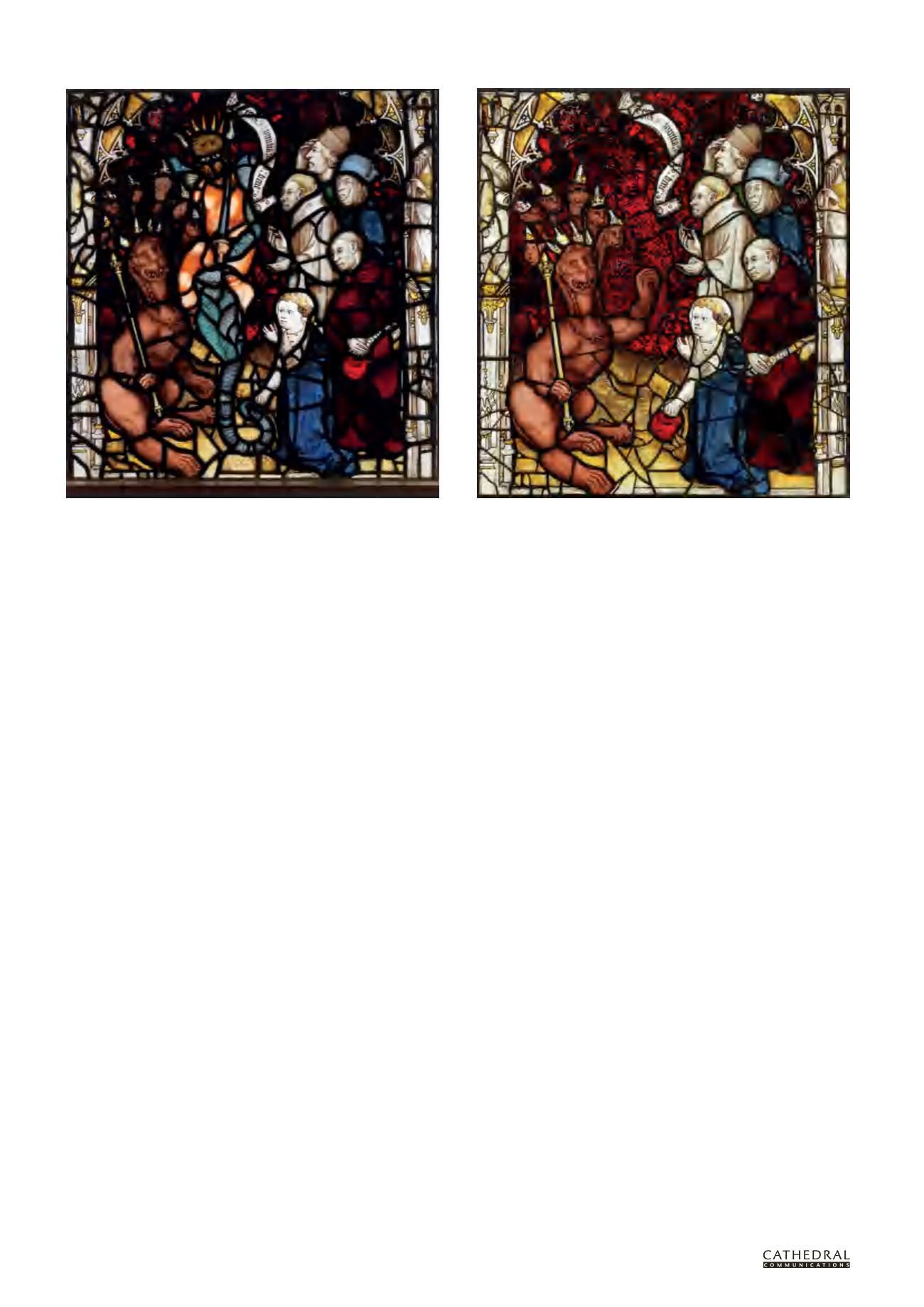

The panel following conservation in 2013: ‘And they adored the beast, saying

‘Who is like to the beast? And who shall be able to fight against him?’

(Revelation 13: 4–6).