14

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

MORTAR

The pointing and bedding mix is made

up of naturally hydraulic lime (NHL 3.5,

usually St Astier). The standard mix for

general pointing uses one part sieved

washed river sand (Nosterfield), one part

Leighton Buzzard sand, one part South

Cave sand and one part NHL 3.5 St Astier.

This mix provides an extremely well-

graded aggregate proportion which bears

a very close resemblance to the colour

and technical performance of the historic

mortars used at the Minster. Where

necessary wide joints are ‘galleted’ using

shards of oyster shells to fill the gaps and

reduce the area of mortar exposed to the

weather, closely following earlier examples

found on the Minster, some of which date

from the medieval period.

REPAIR WORK

The full size drawings and templating

for every individual piece of stone were

prepared by the Minster’s master mason

and geometry and carving details were

agreed with the surveyor of the fabric. The

work was carried out in accordance with

the ‘Current Stone Practice’ document,

prepared by the surveyor of the fabric.

The document sets out a detailed

methodology and specification for both

conservation and new work.

The new tracery indents were

secured in place using lead-poured

joints, a technique used in the Middle

Ages to create a rigid joint. These were

then pointed up with the standard

mortar. The surface tooling of all

new stonework followed established

medieval practice and all surfaces

were carefully worked using a ‘grozed

edge’ chisel, a form of claw chisel.

Almost every surface of the building

The design of individual tracery

elements involves a great deal of lobe and

cusp work and many of the cusps and

tracery profiles were missing as a result of

weather and fire damage over the years.

Although traditional lime-based mortars

are used for weathering and filling, where

profiles need to be restored and/or rebuilt,

a repair mortar with a greater degree of

slump resistance is needed. Keim’s Restauro

mortar system met this requirement well

and the mortar can be chiselled and dressed

when it has hardened. The product’s

porosity and breathability also closely

match those of the host stone. Lost profiles

have therefore been rebuilt using these

mortars with careful colour matching, and

reinforced with either stainless steel wire

or hollow ceramic dowels.

A HISTORIC ACHIEVEMENT

John Thornton’s 300-panel representation

of the biblical Apocalypse in medieval

stained glass was a ground-breaking

achievement.

The task of meticulously recording,

conserving and reinstating the Great East

Window’s stained glass and stonework

has brought together art historians,

archaeologists, conservators and

craftspeople. One of Europe’s largest and

most complex conservation projects, the

scale and success of this collaboration

echoes that of Thornton and those who

worked alongside him. And the results

speak for themselves, as the quality

and sophistication of John Thornton’s

monumental design have re-emerged from

centuries of obscurity, no longer ‘a glorious

wreck’ but a magnificent work of art.

Recommended Reading

A Bernardi et al, ‘Conservation of Stained

Glass Windows with Protective Glazing:

Main Results of the European VIDRIO

Research Programme’,

Journal of Cultural

Heritage

, vol 14/6, 2013

S Brown,

Apocalypse: The Great East

Window of York Minster

, Third

Millennium Publishing, London, 2014

Corpus Vitrearum,

Guidelines for the

Conservation and Restoration of Stained

Glass

, 2nd ed, Nuremberg, 2004 (www.

cvma.ac.uk/conserv/guidelines.html)

N Teed, ‘Bronze Framing for Historic

Stained Glass: A New Case Study from

the York Glaziers Trust’,

Vidimus

88,

Feb 2015 (vidimus.org/issues/issue-88/

feature-ygt)

ANDREW ARROL

is surveyor of the fabric

for York Minster and a partner of Arrol &

Snell Ltd (see page 45).

SARAH BROWN

is director of the York

Glaziers Trust (see page 10).

was covered externally with linseed oil

during the 19th century and this has led to

a surface consolidation process which can

trap salts and sulphates in the outer zone

of all external masonry elements. After a

while this develops into a kind of ‘potato

crisp’ which then snaps and breaks off.

Such surfaces were carefully cleaned with

distilled water then stabilised with up to

six applications of nano lime followed

by shelter coating using limewashes

emulsified with casein and a small amount

of ochre pigment.

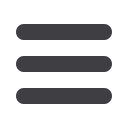

View from scaffold of tracery section showing poor condition of stonework and diamond paned protective

glazing installed c1925

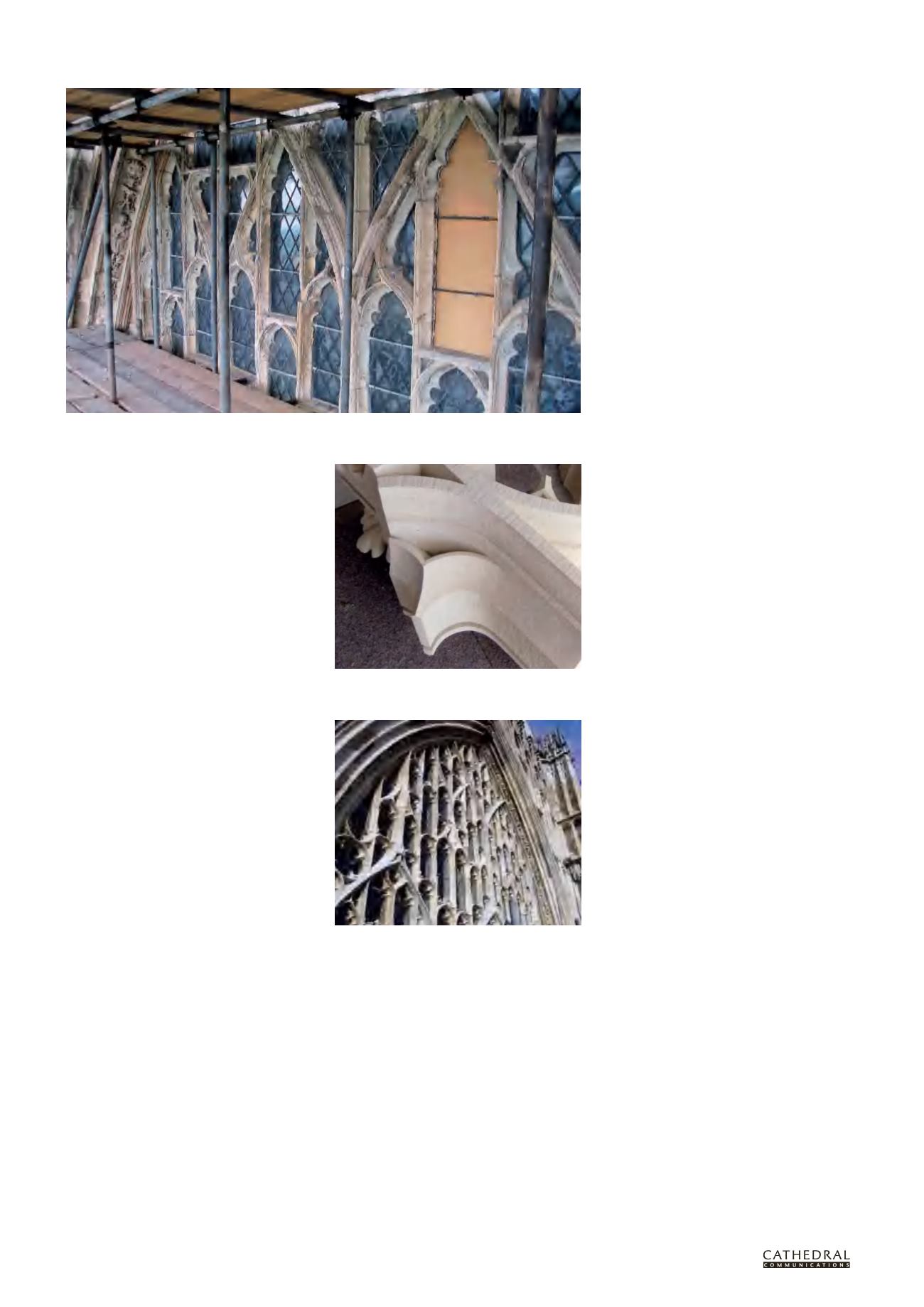

Detail of a new tracery section ready for indenting:

note grozed chisel finish to all surfaces

Upper part of the Great East Window with masonry

complete and protective glass in place