BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

7

TYPES OF LEDGER STONE

Most ledger stones are quite large,

measuring 76 by 183cm, although as

they were cut in the age of Imperial

measurement this can be translated to

30 by 72 inches. Types of stone vary; the

most common is black marble, although

they were also available in white marble,

Purbeck stone and Portland stone and

there are also examples in cast iron.

Black marble ledger stones sometimes

incorporate other coloured marbles, for

example in the form of an inset roundel of

white marble at the head end of the stone

depicting the armorial bearings of the

deceased. Some ledger stones have infilled

lettering, usually of white mastic, while

others have brass lettering and there are

still a few which bear traces of gilding.

While most ledger stones are marble

some are freestone (usually a local

fine-grained limestone or sandstone),

but in the main these were only used as

temporary sealing stones. Many survive

simply because the family had relocated.

Indeed, the majority of such stones were

laid following the burial of a child during

the early years of a couple’s marriage and

while the grave was intended for further

use this rarely took place if they had

moved to another town. Unfortunately,

freestone does not retain inscriptions well

and many of the legends have now eroded.

INSCRIPTIONS

Ledger stone inscriptions are usually

in English but some, particularly those

commemorating the clergy, are in Latin.

There are also some Huguenot burials in

City of London and Norwich churches

whose ledger stones are inscribed in

French, but these are very rare.

The standard legend begins ‘Beneath

this stone lies…’ or ‘Here lies deposited

the remains of…’. It was standard

practice for the font size of the name of

the deceased to be larger than that of

the rest of the inscription, sometimes

in italics, and the usual initials denoting

academic honours, such as ‘BA’ or ‘MA’,

were frequently used, although the longer

forms ‘Bachelor of Arts’ or ‘Master of

Arts’ were occasionally used.

Some ledger stones begin with ‘HJ’

or the fuller ‘

Hic jacet

’, which means

‘Here lies’, although ‘HLD’, for ‘Here lies

deposited’ is sometimes seen. The use of

initials was, at least in part, a question of

economy: the cost of cutting ‘HLD’ would

have been far less than for the 17 letters of

‘Here Lies Deposited’ when one was being

charged by the letter. Similarly, a Latin

translation of an English inscription could

land the purchaser with a bigger bill if it

made the inscription longer.

Some ledger stones have exceptionally

short inscriptions, but this does not mean

that the lettering is any more crude than

those with a longer legend. Probably

the shortest would be the name of the

deceased and the year of death, such as:

JOHN SMITH

1801

whereas those which were to be read

in association with an adjacent mural

monument had simpler markings, such as:

J S

1801

merely to indicate the place of burial.

Furthermore, if the mural monument

is signed by a sculptor, that may give an

indication of the artist also responsible for

the lettering on the ledger.

LETTER-CUTTERS AND MASONS

The provision of ledger stones, particularly

in the 18th century, was usually limited

to letter-cutters working in the larger

towns. Much of the black marble used was

imported by merchant ships as ballast so

letter-cutters’ yards were often based in

ports. For example, the Stanton family of

letter-cutters had their yard in Holborn,

close to the wharfs along the commercial

stretch of the River Thames. Similarly,

Britain’s extensive system of navigable

rivers and canals was used to transport the

finished items to their destinations. Indeed

the cost of transporting a heavy ledger

stone to a remote rural church was almost

the same as the cost of the stone itself.

The inscriptions usually begin with

the name of the prominent male in the

grave and it is not unusual to discover

from the inscription that he died some

years after the death of his wife, which is

further evidence of the use of a temporary

freestone ledger before the final one was

put into position. However, there are

examples of black marble slabs which have

space left at the top for the primary name,

which is an indicator that the husband

married again and is buried elsewhere

with his second wife. Subsequent

inscriptions were usually cut in situ, which

explains the use of a different ‘chisel’

or letter-cutter’s hand if the original

letter-cutter was no longer in business.

Laying a ledger over a brick grave

was a delicate operation for they were

bulky and unwieldy items, frequently

as much as 15cm (6 inches) thick. Once

the temporary stone had been lifted

and discarded, three or more wooden

bars were placed across the width of the

grave and eight men, holding the ends of

four lengths of canvas webbing passing

beneath the slab, would take the strain as

the wooden bars were removed. The slab

was then manoeuvred into position.

Subsequent re-openings of a brick

grave can often be identified by the chips

around the edge of the ledger stone

where crow-bars were used to lift it onto

wooden rollers for temporary removal.

LOCATION

The location of burial places in the church

depended on the role and status of the

individual being interred. Consequently,

ledger stones over the graves of clergymen

are usually to be found in the sanctuary or

chancel, although some benefactors were

also afforded that position. Prominent

members of the community are usually

found either in the centre alley of the nave

or, if they required a more substantial

vault, at the east end of the nave side

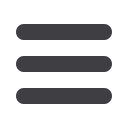

Densely packed ledger stones in the north choir aisle

at Norwich Cathedral (Photo: Roland Harris)

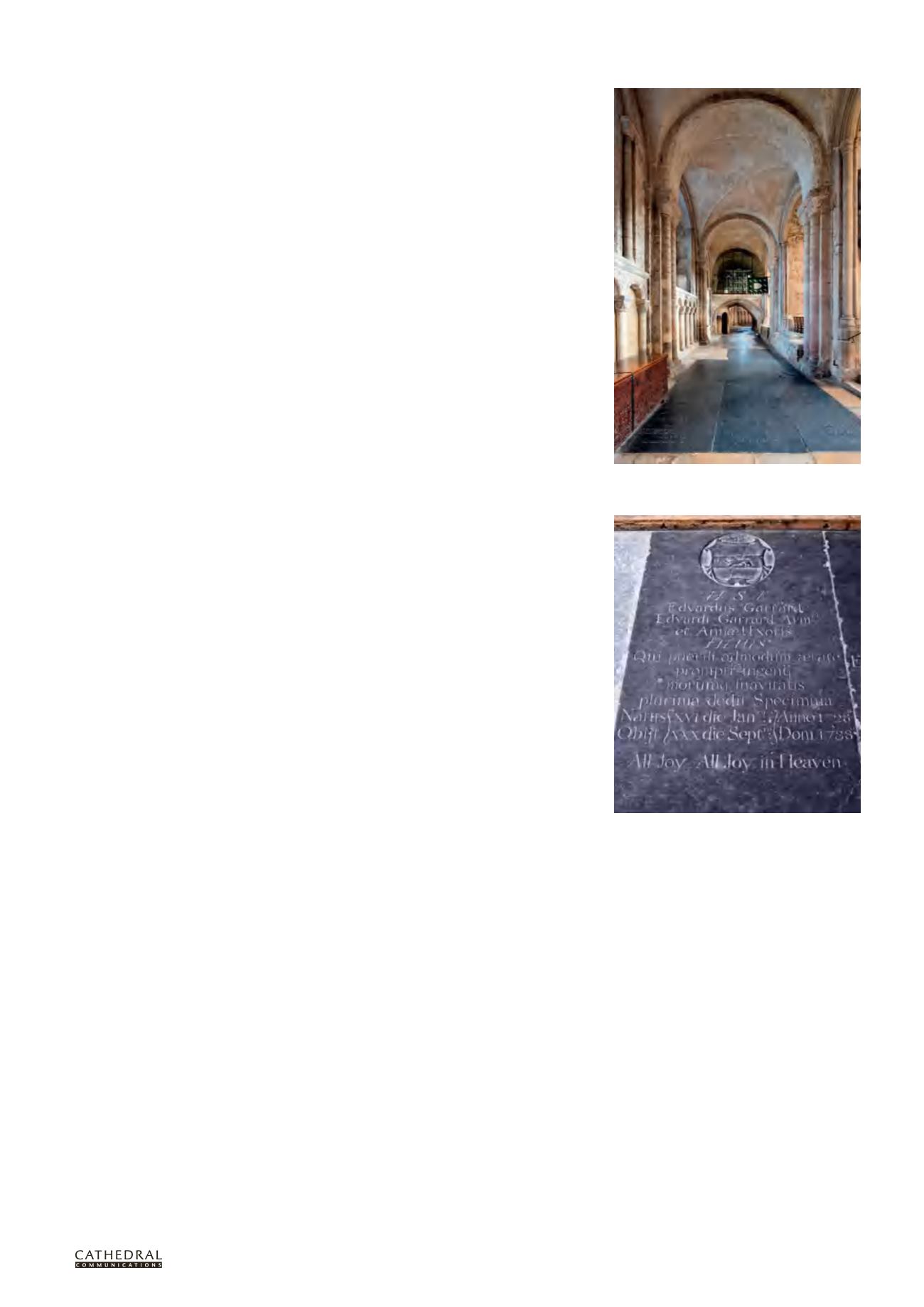

18th-century ledger stones in the Church of St Thomas

and St Edmund, Salisbury: chipped edges often

resulted from the use of crow-bars to reopen a vault

after the original burial. (Photo: Jonathan Taylor)