6

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

burial would have been made

much easier had Ralph Bigland’s

recommendations of 1764 (see

Recommended Reading) been

carried out:

Many grave-stones are often

half, and others wholly covered

with pews, &c. many also are

broken, and by the sinking of

graves not only inscriptions are

lost, but the beauty of the church

defaced; all these and many

other evils might be remedied, in

case every parish was obliged to

have, in like manner as abroad,

a monumental book, under

the inspection of the minister

officiating; for which purpose a

fee should be paid: nor would it

be amiss, if every parish had the

ichnography of the church on a

large scale, with proper reference

to each person’s grave or family

vault. This ought especially to

be done when any old church

is repaired, or pulled down in

order to be rebuilt. (p79)

Intramural burial was an expensive

exercise. In addition to the fee

paid to the incumbent for the

privilege, one has to consider

the cost of digging the grave,

lining it with bricks to a depth

of, say, ten feet for two coffin

deposits, and the purchase,

lettering, transport and laying

of the ledger stone. Translated into

today’s prices this could cost up to

£25,000, which was a substantial

outlay on the part of the purchaser and

which, no doubt, explains why there

are so few ledger stones in churches.

Indeed, the ledger stone phenomenon

was short-lived, for the

Burial Act

of 1854

prohibited intramural burial in favour

of municipal cemeteries, although there

was a caveat in the act that where space

was still available in a vault or brick grave

constructed prior to the date of the act,

it could be used until all of the space had

been taken up at which time it would

be deemed ‘full’. Generally, then, ledger

stones were in use between 1625 and 1854.

LEDGER STONES

Julian Litten

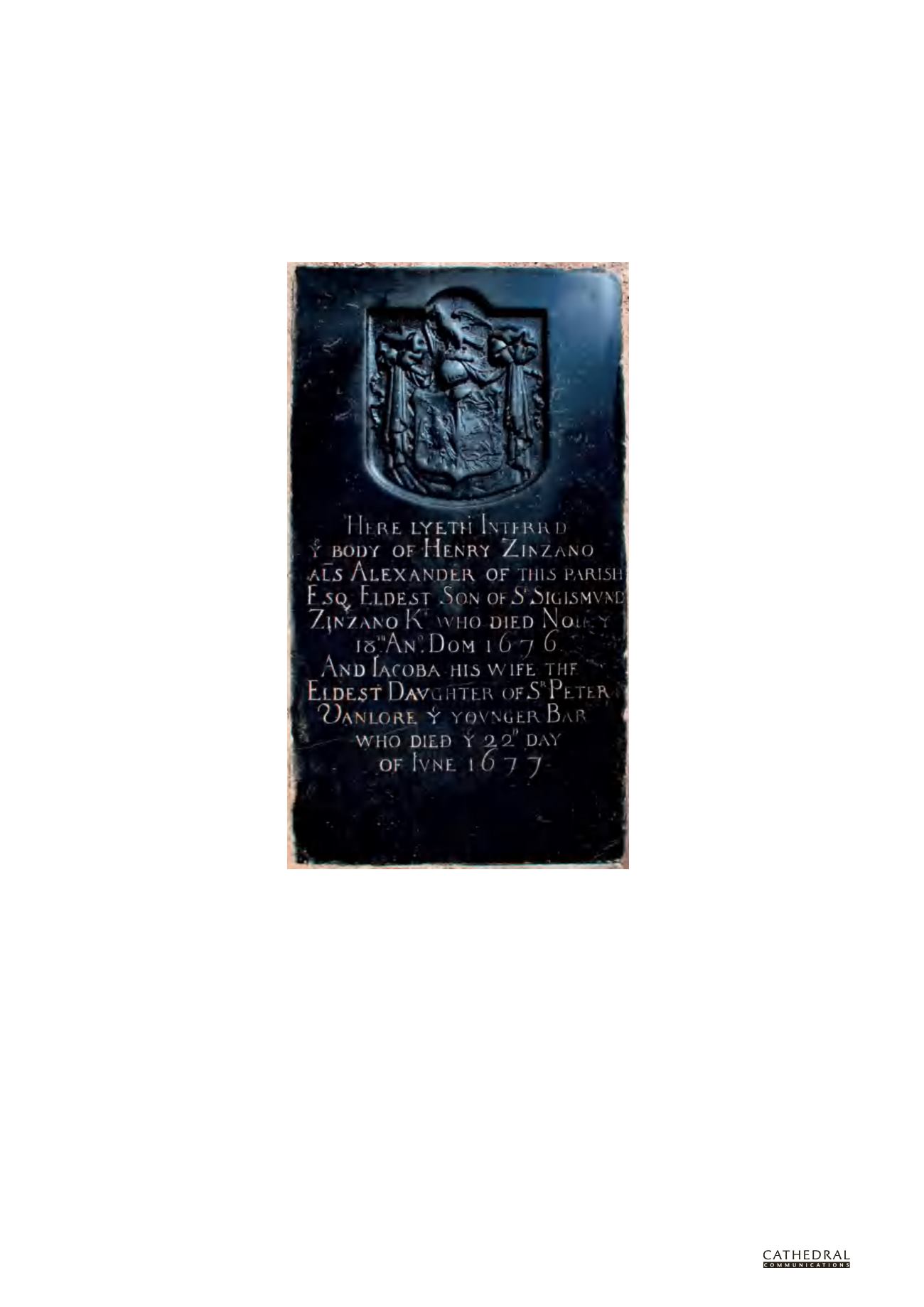

I

F YOUR church was built

before 1800 there’s every

possibility that it contains

at least one ledger stone, a large

black or white marble slab set into

the floor and inscribed with the

names of those interred in the

brick grave beneath.

Sometimes known simply

as ‘ledgers’, they can be highly

decorative, incorporating the

deceased’s armorial bearings, while

others have a funerary motif such

as an hourglass with wings or a

death’s head wearing a laurel-

wreath. Most, however, consist

simply of an inscribed legend

without attendant relief-sculpture.

Whatever form they take, the

genealogical information they bear

is of paramount importance.

INTRAMURAL BURIAL

As a rule of thumb, ledger stones

began appearing in churches in

the 1620s. However, it was during

the Commonwealth (1649–1660),

when faculty jurisdiction was

suspended, that the middle classes

looked to the interior of their

parish church as a place of secure

burial. Permission for intramural

burial would be sought from the

incumbent, the individual deemed

the most worthy arbiter of suitable

candidates for such a privilege.

With the restoration of the monarchy

in 1660 the practice of intramural burial

was so established that the ecclesiastical

authorities thought it best not to

interfere, apart from requiring a faculty

for the creation of a brick grave or vault

(often simply a double width brick grave)

and for the laying of the ledger stone,

although in practice such faculties were

rarely sought.

We shall never know precisely how

many bodies have been buried within our

medieval parish churches because burial

registers were not introduced until 1538

(and most churches did not take up the

practice until legally required to in 1598).

Few burial registers, however, give the

Zinzano ledger stone of 1676 at Tilehurst, Berkshire:

a fine ledger with carved armorial (Photo: Julian Litten)

location of the burial unless it was in the

large dynastic vault of a noble family.

Nevertheless, a hint as to the

differentiation between those buried in

the church and those in the churchyard

can be found in the burial register entries

because those individuals afforded

intramural burial almost always appear

with a title of courtesy. Thus a ‘John

Smith’ or a ‘Janet Smith’ would be

churchyard earth burials, whereas ‘Mr

John Smith’ or ‘John Smith Esq’ and ‘Mrs

Janet Smith’ or ‘The Hon Mrs Janet Smith’

would be intramural burials.

With hindsight, understanding the

usage of a church as a place for intramural