BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

3

brought more wealth to the region. All

this changed, however, with the building

of St Petersburg by Peter the Great. With

a port that remained ice-free for ten

months of the year, St Petersburg became

the window to the west and northern

Russia became increasingly isolated and

sank into obscurity.

During the mid to late 19th and

early 20th centuries there was a revival

of interest in the north, this time

ethnographic rather than economic.

Leading historians, musicologists, artists

and architects travelled to the north.

While working as an ethnographer

in 1889, the artist Vasily Kandinsky

described the peasants as ‘so brightly

and colourfully dressed that they seemed

like moving, two legged pictures’. In

1904 the artist Ivan Bilibin wrote of the

bell tower at Tsyvozero, ‘she is living her

last days, she has leant over sideways

and trembles in the wind. The bells have

been taken from her’ (110 years later she

is still hanging on). The painter Vasily

Vereshchagin complains, in 1894, of the

neglect of the churches by the local clergy:

I wish they had even a brief course

in the fine arts at the seminaries. If

priests who have responsibility for

the old churches do not show mercy

and unceremoniously demolish

them, what can we expect from

the semi-literate country fathers.

They are ready to sacrifice every

ancient wooden church for a gaudy

new stone church, embellished with

manneristic golden baubles.

If the custody of the wooden churches

by the priesthood was shoddy, their

custody by the local Soviets after the

revolution was catastrophic. The artist

Ivan Grabar and the architect and

preservationist Pyotr Baranovsky joined

the campaign to save the northern

wooden architecture. In 1921 Baranovsky

undertook the first of ten expeditions

to the north to study its architecture:

In the villages on the banks of the

Pinega there were so many churches

that were ‘extremely miraculous’ that

I decided that come what may, I would

go up the river to its very source.

You arrive in a village and there

are two or three tent-roofed church

beauties, three-storey wooden houses,

mill‑strongholds – and all of them

first-class architectural masterpieces…

I don’t know anything more miraculous

than Russian wooden architecture!...

It is hard to acknowledge the fact that

the descendants of those who raised

this miracle with their calloused

hands, destroyed the glory of their

great-great grandfather’s father.

And destroyed they were, no wooden

church survives on the Pinega river today.

Those that did survive in the north were

used by the local Soviets as warehouses,

grain stores, clubs, garages, dance halls

and cinemas. Most were left to rot.

After the ‘Great Patriotic War’

against Nazi Germany and its allies,

during which God had been reinstated

by Stalin to fight on the side of Holy

Russia, there was an effort to restore

the wooden churches that had

survived. They were recognised as a

great symbol of Russian culture, the

culture that the Russian people had

been fighting desperately to preserve.

In 1948 the architect Alexander

Opolovnikov (1911–1994) supervised the

restoration of the wooden Church of

the Assumption at Kondopoga. With his

team and later with his daughter Elena

(1943–2011) Opolovnikov restored over

60 monuments of wooden architecture

and much of what we see today, including

the churches at Kizhi and the Cathedral of

the Assumption at Kem, survives thanks

to them. Opolovnikov also produced

technical drawings of the churches and of

their construction details that are great

works of art.

With the break-up of the Soviet

Union, funds disappeared and most

restoration came to a halt.

STOPPING THE ROT

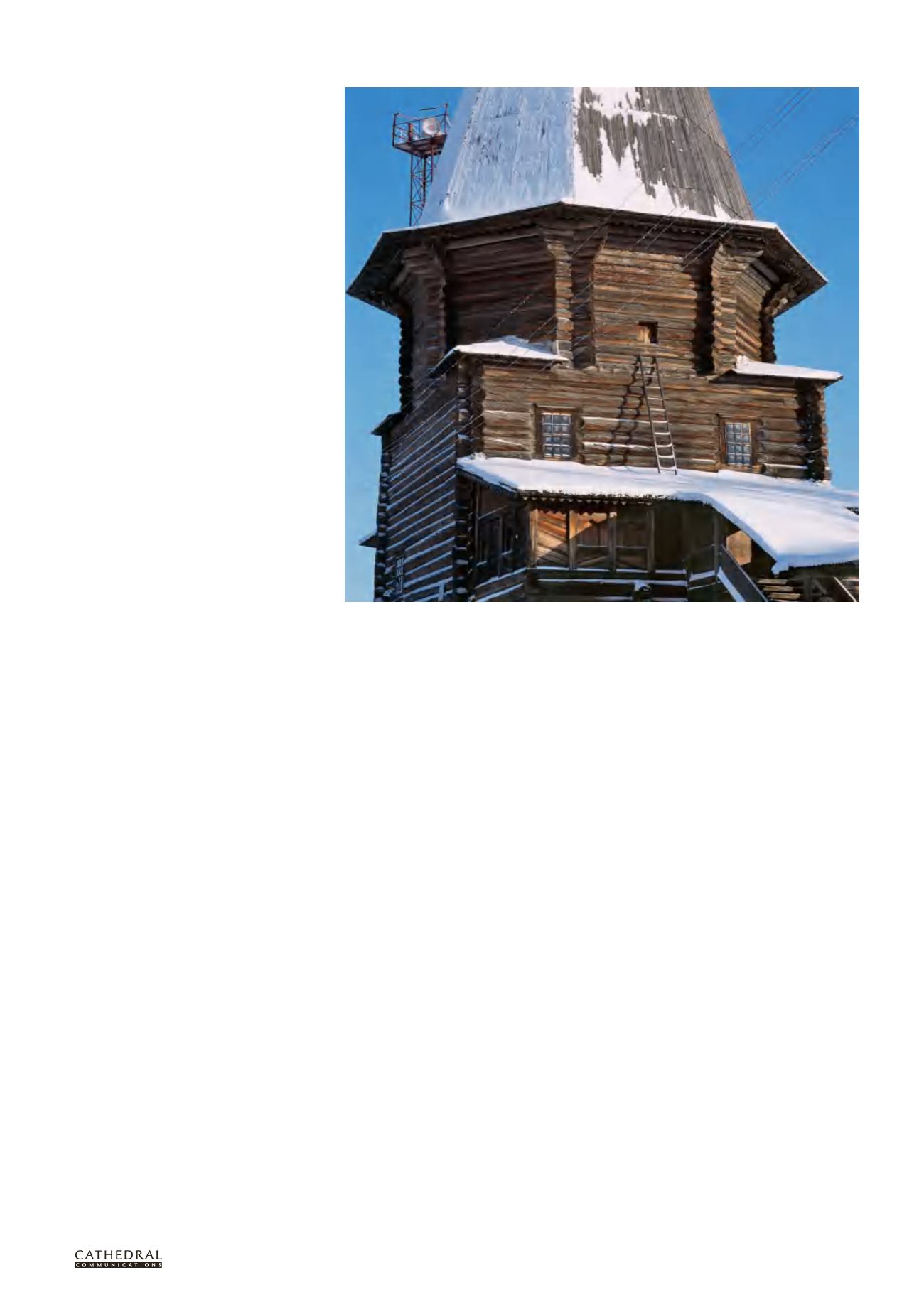

The first wooden church I visited, in

2002, was the 43-metre high Church of

St Dimitrius of Thessalonica at Verknaya

Uftiuga. I later learned that Alexander

Popov, a student of Opolovnikov, and his

team had spent seven years from 1981

to 1988 restoring St Dimitrius. They had

completely dismantled the church, rotten

timbers (15% of the whole) were replaced

and then the building was reassembled

log by log. The logs were up to 12 metres

long and some weighed as much as two

tons. Popov, like Opolovnikov, is very

rigorous in his research and methods and

at Verknaya Uftiuga he experimented

with the local blacksmith to produce

carpenters’ axes based on sketches of axe

heads found by archaeologists in Siberia.

He was keen to use the same techniques

and tools as the builders of 1784.

In 2011 I asked Mikhail Milchik,

vice director of the St Petersburg

Research Institute of Restoration and

a great expert on Russian wooden

architecture, to write an afterword to

Wooden Churches: Travelling in the

Russian North

. He was not optimistic,

his first sentence read, ‘Wooden

Architecture, the most original and most

unique part of the cultural heritage of

Russia, is on the verge of extinction’.

Almost four years on I’m slightly

Church of St Dimitrius of Thessalonica (1784), Verknaya Uftiuga, Krasnoborsk district, Archangel region