24

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

of the beauty and value of gold with the

durability, workability and lower cost of a

copper-based alloy. However, unlike gold,

it is not inert and it will oxidise slowly if

not protected by wax or lacquer.

Sheet brass is made by hot-rolling

and cold-rolling cakes of alloy until the

desired thickness and size is achieved.

The forging and rolling of brass causes

work-hardening and embrittlement so

the metal has to be annealed in between

working – that is, heated to a temperature

that allows the metal crystals to rearrange

themselves, with the reduction of internal

stresses leading to a softening of the

brass. Repairs to badly damaged sheet

brass artefacts may also require annealing

before the metal can be reshaped.

Brass for casting can contain some

lead as this reduces the melting point and

makes it easier to pour when molten. Lead

has also been added to brass to make it

easier to machine, for example for making

plumbing fittings with screw threads. In

recent years concerns have been raised

about the lead content of brass used for a

variety of items, including pipe fittings, due

to the leaching of lead into drinking water,

and even brass keys due to the potential

transfer of lead out of the metal and onto

skin during handling. Today the amount

of lead allowed in brass for such uses has

been strictly limited in some countries.

However, the author is not aware of

concerns about the lead in items of church

brasswork, presumably because no health

problems have been reported or detected.

Brass is relatively resistant to tarnish,

yet is malleable and easy to work in sheet

form or cast into a mould to make heavier

pieces, and components are easily joined

together by brazing, soldering or riveting.

It also takes well to polishing where the

use of increasingly fine abrasives leads

to the production of a smooth bright

surface. This contrasts with copper and

bronze which have less useful working

characteristics, and which tend to

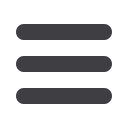

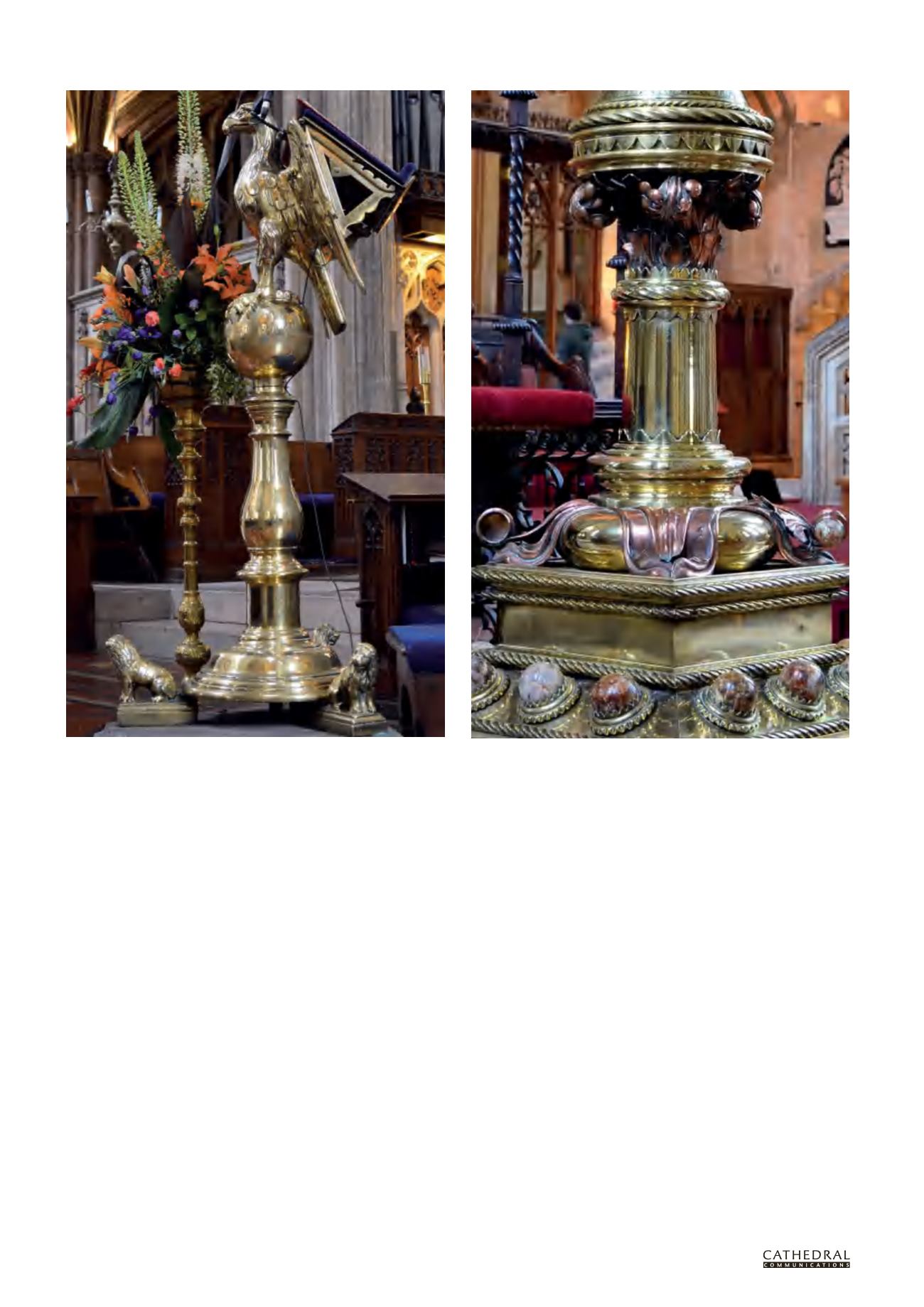

An eagle lectern in St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol dated 1638 (left) and a detail (right) of the base of a late 19th-century eagle lectern in Bristol Cathedral: the ornate

scroll-work is of copper, which is particularly vulnerable to accidental damage. (Photos: Jonathan Taylor)

tarnish rapidly if cleaned and polished.

Indeed, bronze and copper are normally

deliberately patinated as otherwise the

task of maintaining a bright and attractive

surface would be endless. But brass can be

maintained in a bright state with relatively

little effort if the general conditions in

which it is kept meet reasonable standards.

Coatings should be mentioned as

they can present significant issues. Brass

can be gilded either by oil-gilding (when

gold leaf is applied to the surface with

an adhesive), by mercury-gilding, or by

electroplating. The layers of gold applied

are very thin and can easily be removed by

inappropriate treatment. Brass may also

be protected by a durable lacquer which

will prevent tarnishing, but if the lacquer

is damaged, the exposed area of metal

will tarnish, creating visibly darker areas.

The most problematic items are those

that once had a coat of lacquer which

has been partially removed by cleaning

and polishing efforts, leaving a sort of