22

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

not ideal, in some circumstances you

will have to accept that there is no other

sensible answer, but it can be a difficult

case to argue with the DAC.)

POSITIVES

The paint is low cost, readily available and

easy to apply.

NEGATIVES

It is prone to static and particulate greying

especially over heaters. It is also prone to

scratching and staining.

Mineral Paints

Also known as silicate paints, these highly

porous paint systems are based on mineral

silicates which bond with a lime or stone

substrate through the development of

an insoluble microcrystalline structure.

They are stocked by most specialist

conservation materials suppliers. Free

from organic solvents, plasticisers and

biocides, they are naturally resistant to

mould and fungal growth and are suitable

for allergy sufferers. Surfaces are cleanable

and resistant to disinfectants making

the paint suitable for application in food

preparation areas.

POSITIVES

Mineral paints adhere to all types of

surface (but often require an undercoat

in order to equalise absorbency of the

general wall surface) and they come in a

wide range of whites and other colours.

There is good technical support on

site and over the phone, and detailed

technical literature is provided. They

are not prone to static and particulate

greying, and do not degrade in sunlight.

They have a long life and performance

warranties are available as long as the

selling agents approve the specification

and attend site occasionally.

NEGATIVES

Mineral paints are relatively high cost,

particularly if sealants and undercoats are

required (this depends on the underlying

properties of the painted surface). They

are unsuitable for use where historic

paint schemes might exist as mineral

paint systems are designed to penetrate

the underlying painted surfaces and

are almost impossible to remove. All

unpainted surfaces including stone

detailing, monuments and furnishing

must be protected as this type of paint

dries quickly and is non-reversible.

Limewash

The paint used traditionally both

internally and externally, limewash is

the most vapour permeable option.

Although less durable than modern

alternatives, it is ideal for lime plastered

and rendered walls, or for bare masonry

pointed with lime mortars. It can be

cheaply made by diluting lime putty,

and earth pigments such as ochre may

be added if a colour wash is required.

A binder such as linseed oil or tallow is

sometimes added, particularly for external

use, and an increasing number of new

formulations are being developed to

broaden its application. Limewash has

a very attractive appearance internally

and externally, good shadowing and

sunlight reflection, and it can be

reapplied in small areas where paint

surfaces are prone to damage.

POSITIVES

Limewash is a highly permeable, low-

cost option which can be used on old

limewash and lime plaster. It can also

help to consolidate friable lime surfaces.

It retains an attractive appearance over

long periods of weathering and use. It is

also historically appropriate in many older

churches where it was the original finish.

NEGATIVES

Limewash cannot be used on

impermeable surfaces or over modern

non-porous paint systems (although

it is often possible to remove a non-

traditional paint, particularly where

there are underlying coats of limewash).

It requires a large number of colour

wash coats to build up opacity.

Decorators require hand and eye

protection due to its caustic effect.

In conclusion, no matter what paint is

specified it will quickly degrade if the

underlying painted surface has not had

sufficient time to dry out following

repairs, or if loose paint has not been

thoroughly removed. Make sure the

plasterwork is only repaired with lime-

based or renovating plasters no matter

how small the hole. Fillers of any sort

should not be specified or allowed. Open

joints, particularly where the walls abut

timberwork, must not be sealed in order

to allow the timber to ventilate. Open

joints in the masonry construction require

repointing using a natural lime mortar

and, finally, surface waterproofing agents

such as water soluble PVA (Polyvinyl

acetate) should never be used.

Further Information

N Ashurst,

Cleaning Historic Buildings,

Vol 1, Donhead, Shaftesbury, 1994: Ch 7

describes paint removal and how to

apply traditional alternatives.

G Davies, ‘Vapour Permeable Paint’,

The Building Conservation Directory

,

Cathedral Communications, Tisbury,

1996

(http://bc-url.com/vapour): article

on the use of traditional limewash and

contemporary alternatives

English Heritage,

Practical Building

Conservation: Building Environment,

Ashgate, Farnham, 2014: large volume

with comprehensive coverage of

humidity and permeability issues

Internet search term: ‘

traditional vapour

permeable interior paints’

: provides links

to all of the current manufacturers and

companies which market their products

Internet search term: ‘

traditional lime and

renovating plaster’

: provides links to all

current manufacturers of traditional and

renovating wall plasters and companies

which market their products.

MARK PARSONS

is an architect accredited

in building conservation (AABC) and a

partner in the practice of Anthony Short &

Partners LLP in Ashbourne, Derbyshire (www.

asap-architects.com). He is responsible for the

quinquennial inspections of 130 churches in

the dioceses of Derby, Southwell and Lichfield.

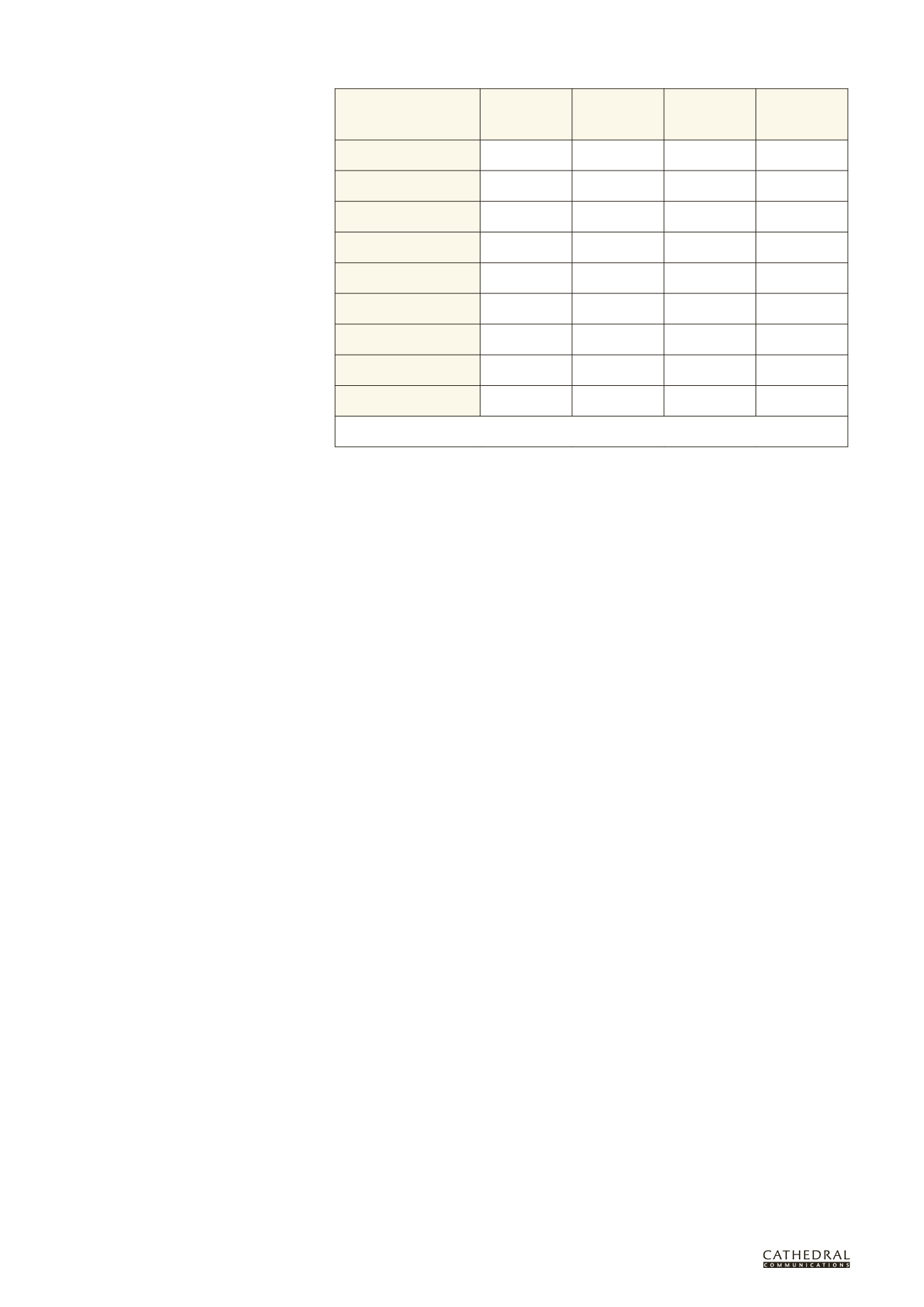

CHARACTERISTICS

One-coat

(eg Classidur)

Contract

matt emulsion

Mineral paint

(eg Keim& Beeck)

Limewash

Vapour permeability

Very good

Varies

1

Very good

Excellent

Reversibility

Varies

2

Varies

2

Very poor

Excellent

Cover

Excellent

Good

Good

Poor

Adherence on moist ground

Good

Poor

Poor

Poor

Durability

Very good

Poor

Very good

Poor

Finish

Flat matt

Matt

Flat matt

Flat matt

Colour retention

Excellent

Varies

Excellent

Excellent

Dilution/cleaning

Proprietary

solvent

Water

Water

Water

Cost

High

Low

High

Low

NOTES

1

Contract matt emulsions with high chalk content have good vapour permeability

2

Film-forming paints are generally easier to remove where underlying layers are of limewash