BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

21

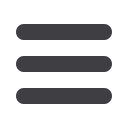

Solid concrete floors following a 20th-century rebuild;

note how the moisture travels up through the renewed

stonework and forms a salty crust on the original fabric.

All the detail has been overpainted in gloss oil paints.

The floor is covered in rubber backed carpeting

surrounding the repair is inconsistent,

particularly in terms of permeability,

and where it is important to provide a

smooth overall appearance

• where it is necessary to work at cold

temperatures (around 10°C) and/or

with high humidity and/or in poorly

ventilated spaces.

One other cause of poor paint adhesion

is the use of inappropriate paints to cover

traditional finishes such as limewash,

casein-based paints and whiting. Where

this is identified as a problem and the

church is ancient or from a period

when complex decorative schemes were

popular, care must be taken when offering

advice on recoating. In these cases you

are required to assume the possibility of

underlying paint schemes that might be

restored at a future date.

Wet penetration caused by a poorly

maintained surface water drainage system

or a system that does not have sufficient

capacity to control the level of water

runoff in heavy rainfall requires careful

consideration. Checks should be made

and action taken where necessary on

basic maintenance and ‘jobbing’ repairs.

Ground conditions at the base of a wall

must also be assessed. Is the area drained

(a French drain or ‘dry area’)? Are there

gullies at the base of the rainwater

downpipes? Soil and debris may have built

up. Sheds and oil tanks may have been

placed against a north wall restricting

evaporation. However, the more

fundamental difficulties often relate to the

general condition of roofs, wall head and

valley gutters.

PAINT ‘SOLUTIONS’

Selecting an appropriate paint system

is thus complicated by the need for

the coating to adhere to the substrate,

which may vary from one area to the

next, and if the substrate remains

breathable, the new paint system must

not trap moisture. Other issues which

also need to be considered include cost

(materials and labour), resistance to

staining from the substrate, resistance

to abrasion, and appearance.

One-coat paints

Specially formulated one-coat paints such

as Classidur Tradition are designed to

adhere to a variety of backgrounds and

substrates without sealants or undercoats,

and have a flat matt finish. These paints

have good vapour permeability, resist salt

formation and retain elasticity over time.

To avoid black spot mildew, one-coat

paints should not be of the ‘plant-based

oil’ (soya) variety. Cover depends on

substrate – further coats may be required

to provide even cover.

POSITIVES

The paint is designed to adhere well to

all kinds of substrate, including moist

backgrounds. It is non-yellowing with

excellent stain-covering properties,

hardens rapidly and has very good

mechanical resistance. As it does not

penetrate into the underlying paints, it

may be used where there is evidence of

underlying limewash and other traditional

paints. Due to its chemical properties

it might be removed as a single layer at

some future date.

NEGATIVES

The paint is relatively expensive. It can be

difficult to apply in some circumstances.

It is only available in white.

Basic (low cost) contract matt emulsions

Emulsion paints are water-based paints

in which the paint material is dispersed

in a liquid that consists mainly of water.

Where suitable these have the advantage

of being fast-drying with low toxicity, low

cost, easy application, and easy cleaning

of equipment, among other factors. On

the basis that low cost means minimal use

of expensive oil-based compounds such as

vinyl, a basic trade product will have high

mineral (packer) content such as chalk.

As a result, the paint will be permeable

to water vapour. (If you are uncertain

whether the paint has a high mineral

content, try using it outside to see how

rapidly it degrades.)

Use where the church does not have

problems with damp or paint adherence,

and where there are already many

overlying coats of emulsion. (Although

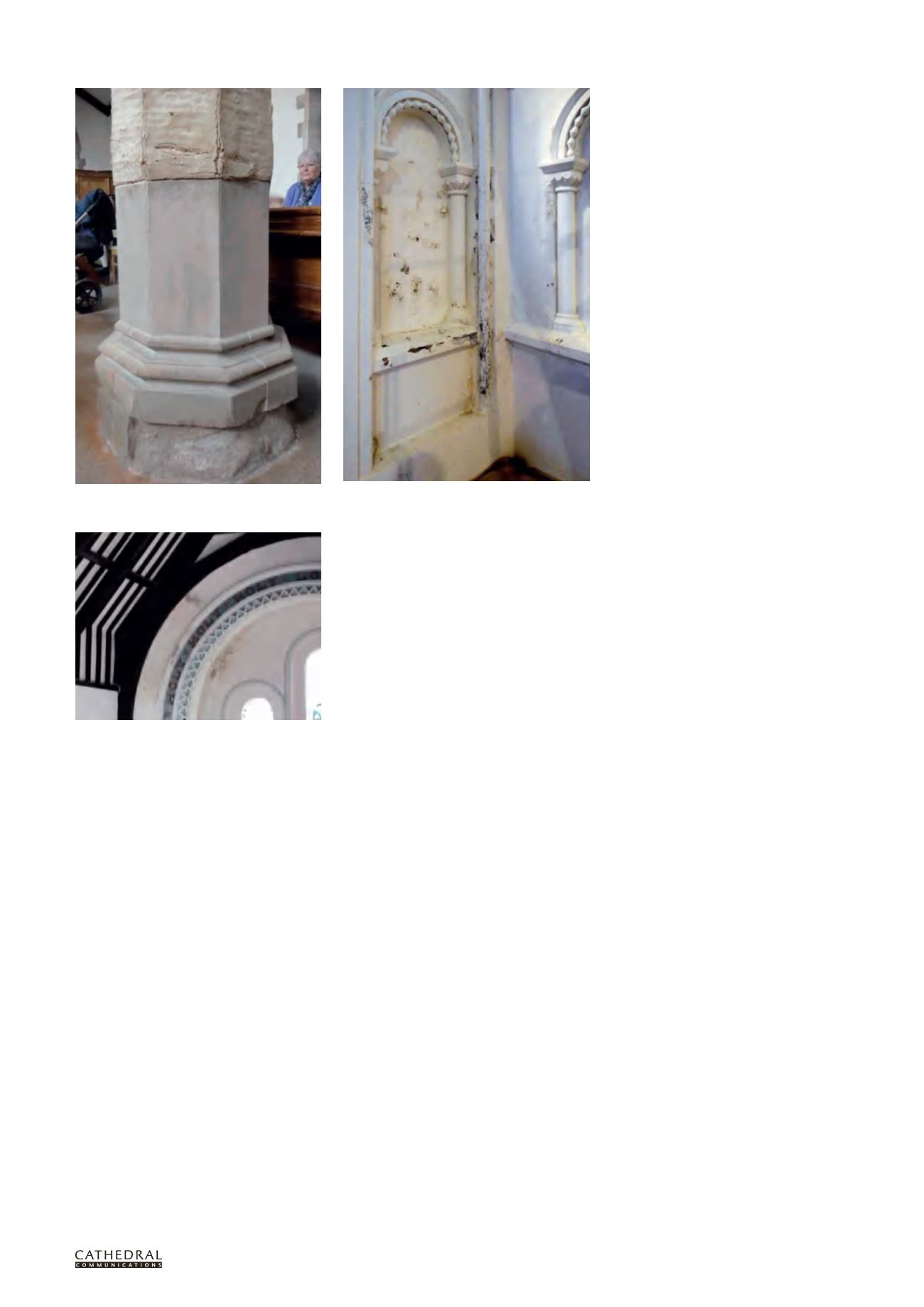

Modern, impermeable paint peeling due to damp

replaced, it is best to use fibre-reinforced

natural lime plasters. However, in some

circumstances an alternative proprietary

lime-rich renovating plaster mix may be

used. Limelite for example contains both

lime and fibrous reinforcement, albeit

with a small amount of cement. When

set, these plasters have a light and open

structure that allows water vapour to

pass through. There are mixes suitable

for upper and lower wall conditions, and

the skim coat adheres particularly well to

all types of surface, even those which are

impermeable. The manufacturers offer

good technical guidance and support.

Proprietary lime-rich renovating

plasters such as Limelite are best used in

the following circumstances:

• where working at high level – wall and

ceiling-renovating plasters are lighter

weight and will penetrate crevices and

timber lath more readily

• where the underlying masonry is

particularly hard, impermeable and

smooth

• as a skim coat where the surface