18

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

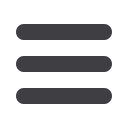

Portrait bust of a patron at St Peter Mancroft, Norwich

A heavily limewashed angel corbel surrounded by

electrical cabling

ubiquitous from the late 14th century

across the country. In East Anglia, angels

also peppered the roof; the hammerbeam

roof of St Wendreda’s March has no less

than 118 winged wooden angels ranged

in rows along the wall-plate, completing

the hammerbeams and perched centrally

on the collars. The most visible are those

beneath the standing saints against

the wall posts, each playing a different

musical instrument. Whether their

function is to support the roof post or

the saint seems to have been deliberately

obscured to emphasise the floating nature

of the roof as an image of heaven.

Even in much less grand churches,

the principal roof timbers are frequently

seen to be ‘supported’ by angels. In All

Saints, Landbeach, north of Cambridge,

there are 15th-century wooden, now

wingless busts in the north aisle, some

with scrolls, some in prayer. Because most

of them emerge from clouds formalised

into triangles, they are likely to be angels.

There is no doubt about the angels on

the stone corbels beneath the south aisle

timbers, because these have wings and

play musical instruments (page 17, top

right). The wooden busts were clearly

added to the wall posts and although the

posts stand on the stone corbels, neither

type of corbel is structurally essential to

the stability of the wall post or principal

roof timber rising from it. Indeed,

there are many examples of wall posts

or principal timbers left ‘hanging’ over

windows. Stone corbels might provide an

element of restraint if the roof ‘racked’

(a horizontal movement of the apex at

right angles to the line of the trusses)

and they were probably useful during

construction. Clearly, however, corbels

were also a neat way of visually linking

a roof structure to the wall, helping it to

seem part of the fabric of the building

rather than just sitting on top of it.

The tradition of using carved stone

corbels perhaps derives from stone

vaults, although their ribs normally rise

from capitals on wall shafts and these

are usually foliate or moulded. However,

Romanesque churches had external

corbels below the eaves which have

their architectural origins in classical

brackets (and before that, the ends of

roof timbers). Although most frequently

carved as human heads, they could be

animals, figures or grotesques. Explaining

the relative lack of external decoration

of churches in comparison with their

interiors, Durandus writes: ‘for although

its outward appearance be despicable,

the soul which is the seat of God is

illuminated from within’. It has therefore

been taken that the grotesques and

gargoyles seen on church exteriors are

there to defend the building (heaven) and

those within it from ever-present evil by

fighting the Devil with his own.

Nevertheless, demonic characters are

also found inside. Bishop Northwold’s

choir at Ely Cathedral (1234–52) has

grimacing heads at the bottom of the

extravagant foliated vault corbels at

all four corners, carved by the same

sculptor as the external corbels. As Revd

Lynne Broughton argues in

Interpreting

Ely Cathedral

(2008), they have been

interpreted as reminders that although ‘the

cathedral signifies the Heavenly Jerusalem,

it is not yet Heaven itself’, so even in the

most sacred of places ‘the darkness of evil

has not yet been overcome’. The famous

Lincoln Imp overlooking St Hugh’s shrine

is a similar, if more mischievous, reminder.

This same interpretation must apply to

those miniature beasties found tucked

away in the spandrels of rood screens and

on the cusped arches of monuments and

sedilia (the canopied niches to the right of

the altar). These fanciful creatures may well

have been used by priests during sermons

or for teaching.

More intriguing are the more

obviously human figures seen on roof

corbels from the late 14th century,

Menacing lion at St Mary’s, Whaddon,

Cambridgeshire