BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

22

ND ANNUAL EDITION

17

We can quickly identify biblical scenes

such as the Nativity and the emblems

of major saints, such as St Catherine’s

wheel. Symbols of the Trinity or Passion

are less well known perhaps, but is there

a message in the small-scale figures,

faces and creatures too? While literacy

increased in the Middle Ages, the great

majority of people entering a church

would not have been able to read (and

in any case, any script was most likely

to be in Latin before the 16th century).

Medieval people certainly recognised

many more scenes from the Bible than

modern churchgoers, but there were

plenty of other sources of inspiration

for painted and carved decoration.

Hagiographical stories were also widely

used to convey Christian messages.

Morality tales like the Three Dead Kings

were also widely known, not least through

the plays regularly performed by travelling

actors and troubadours.

Although we may have over-

romanticised the imagery of church wall-

paintings and windows as the poor man’s

Bible, there is no doubt that a church

building of whatever scale or pretension

was full of meaning to everyone who

entered it. Unfortunately, very few wrote

down their thoughts. However, we do

know a little more from the work of

William Durandus who died in Rome

in 1296. A canon lawyer with a long

Papal career, Durandus became Bishop

of Mendes, in the south of France. His

book

Rationale Divinorum Officiorum

describes the origins and symbolism of

churches and their ornaments in some

detail. He explains that ‘the material

modern churchgoers and visitors might

feel that using pagan, satirical, if not

downright rude sculpture on a church

is sacrilegious. While cathedral guides

might revel in stories about masons

hiding their little jokes from the foreman,

in the end someone paid for the work

and had an ulterior motive for doing

so. It may have been rare for patrons

like a bishop, abbot or earl to become

personally involved at such a detailed

level, but their project manager (with

whatever title he held) certainly would,

if only to ensure he wasn’t blamed if his

master disapproved of the work or its

cost. All we can be sure of is that the

medieval mason was working within

well-known traditions and to an overall

scheme. As today, it can be difficult to

attribute the precise source of an idea

to one member of the design team.

church, wherein the people assemble to

set forth God’s holy praise, symboliseth

that Holy Church which is built in Heaven

of living stones’. Other writers also allude

to church buildings as the House of God

representing heaven on earth. Given the

vast differences between churches and

people’s homes, it is not difficult to see

how this concept worked.

Durandus assigns attributes to

different parts of the building, often

linking them to quotations from the

Bible. So the foundation is Faith, ‘which

is conversant with unseen things’, the roof

Charity, ‘which covereth a multitude of

sins’ (1 Peter 4: 8), the door Obedience

and the pavement Humility, ‘my soul

cleaveth to the dust’ (Psalm 119: 25). The

glass windows ‘are the Holy Scriptures

which expel the wind and rain, that is

all things hurtful, but transmit the light

of the True Sun, that is God, into the

hearts of the Faithful. These are wider

within than without because the mystical

sense is the more ample and precedeth

the literal meaning.’ The latter is an

interesting comment on the practical use

of splays to admit more light through

thick walls but it also illustrates just how

differently medieval churchgoers saw

and understood religious architecture in

comparison to modern observers.

However, that concept of each church

being an earthly image of heaven readily

explains why roofs came to be extensively

decorated with angels, with their principal

timbers rising from corbels fronted by

angels holding the symbols of the Passion,

musical instruments or the coat of arms

of the patron. Such angel corbels become

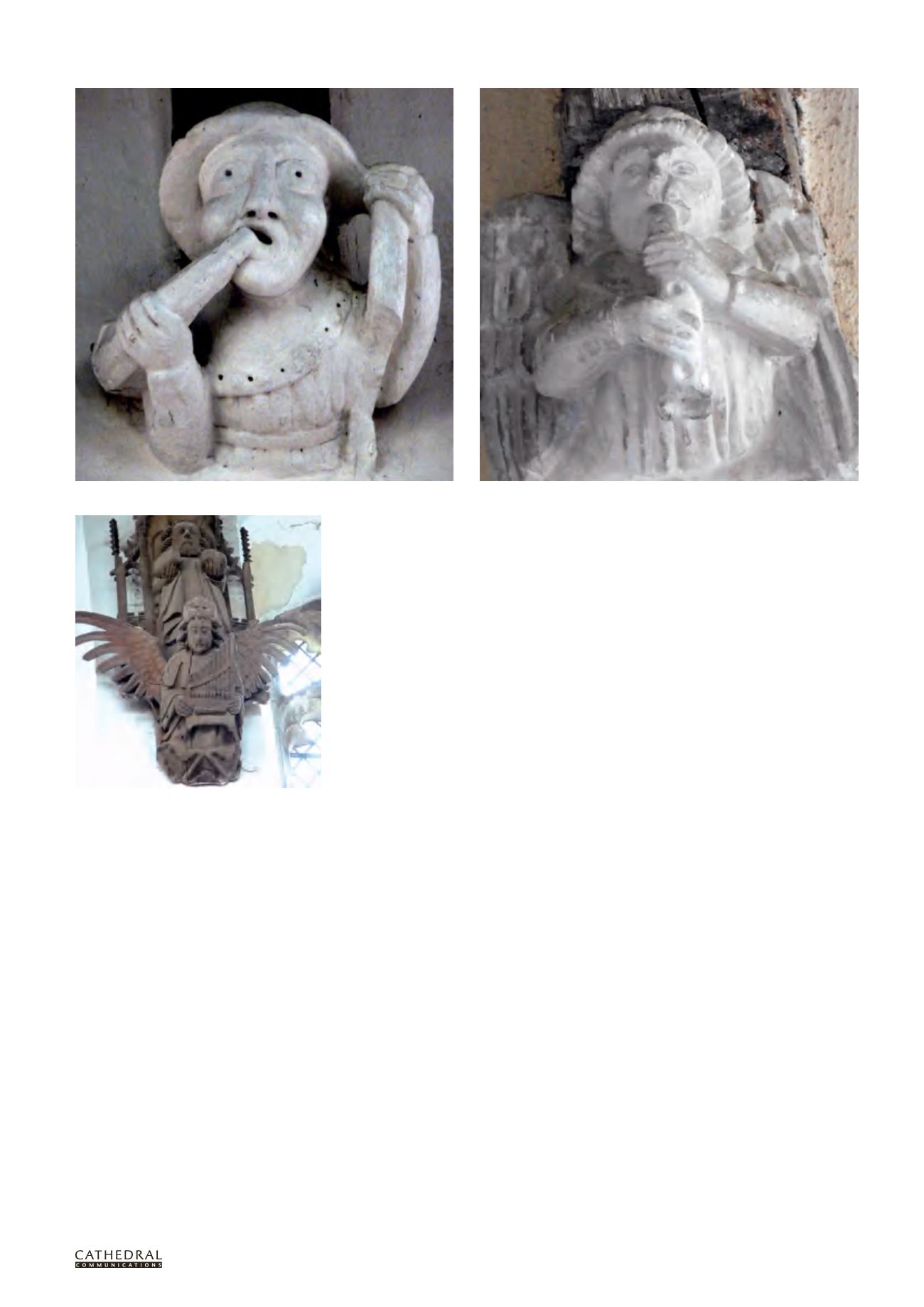

Stone angel corbel at All Saints, Landbeach, Cambridgeshire

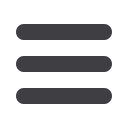

A jolly troubadour or merchant patron at All Saints, Harston, Cambridgeshire

Angel musician at St Wendreda, March,

Cambridgeshire