T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

1 2 5

3.3

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

ME TAL ,

WOOD & GLASS

the problem. By the end of the century these

supply issues had influenced a shift from oak,

as the most commonly used constructional

timber, to softwood.

However, availability was only one of a

number of limitations that had to be overcome

to meet the need for new secular timber

dwellings of a less important nature. These

included the size of available timber and issues

concerning the seasoning, conversion and

workability of oak. Together, these factors

had a direct bearing on the growing trade of

imported softwoods into England for use in

construction.

The carpenter would have been familiar

with these constraints, discussed in more detail

below, which influenced the size and character

of timber frame constructions.

Availability of timber

English

expansionism overseas and the war with

Spain gave the navy shipyards first call on

any quality timber. Navy surveyors became

increasingly aggressive in their demands for

quality timber (defined by its length, soundness

and dimension). A major maritime power for

many centuries, England guarded its timber

supplies jealously, sometimes even going to war

to protect import routes.

Size of available timber

The size of a

building that could be constructed from timber

was dependent on the lengths of straight timber

that was available, as outlined above. With

the depletion of standards grown in managed

woodland, the carpenters were increasingly

reliant on field oaks for the largest posts and tie

beams, but with branches starting lower down

the tree, long straight lengths were increasingly

difficult to find locally.

Seasoning, conversion and workability

Seasoned oak was much harder than

green oak and could not be easily worked,

so oak tended to be worked in its green

state. While the subsequent shrinkage and

distortion of the oak frame contributed

to its stiffness, dimensional instability

also posed significant problems.

Softwood, by comparison, dries far

more quickly than oak and this reduces its

weight and helps to keep it stable. Excellent

softwoods were also readily available from

abroad. Vast tracts of virgin conifer forest

were easily accessible from the Baltic.

Never previously harvested, the trees had

few branches low down and had very large

trunks, so long lengths were available

without knots (‘clear’ grades). As they had

grown in a cold northern climate with short

summers and long winters, the growth rings

were tighter and the timber denser than in

home-grown softwoods, particularly those

from southern England.

Although there was a well-established

timber trade between the east coast of Britain

and the Scandinavian and Baltic ports by the

16th century, it was not until the middle of the

17th century that imported softwoods became

a replacement for the depleted resources of

England’s oak forests. Following the Great Fire

of 1666, large quantities of softwood timber

were imported for the rebuilding of London,

and for the estate building that developed to

the west of the city from the 17th century.

THE SOFTWOOD BOOM

The record demand for house building in

18th-century London was an indicator of the

nation’s prosperity. The demand for buildings

resulted in a demand for timber; that timber

was pine, felled in Poland and sent to England

through the Baltic ports.

The soaring popularity of imported

softwood was driven by its quality and

availability as well as favourable transport and

conversion costs. The quality of slow-grown

old-stand timber such as

Pinus Sylvestris

that

was cut inland and sent down river to the

Baltic ports of Memel and Riga was recognised

by architects and craftsmen of the period.

Contemporary specifications (for example by

English architect Sir John Soane) called for

pine and fir from these ports, including Memel

and Riga Fir.

Slow-grown timber with tight growth rings

and vertical grain was used extensively for

quality joinery such as doors, door-frames and

box-sash windows.

From the 17th century imported softwood

timber was available from Norway and

the Baltic, cut to size using water-driven

frame saws. This reduced transport costs

and enabled carpenters to access timber

with larger sections (baulks). In the 18th

century the use of softwood in carpentry for

trussed roofing, trussed beams and trussed

partitioning became commonplace. The

trussed elements of 18th-century building

construction were designed to be of a

structural nature and were adopted as a result

of architectural influences from Italy where

a wider expanse of ceiling was fashionable in

the principal rooms.

The mid-18th century saw the publication

of many illustrated books promoting new

structural and decorative joinery techniques.

The principles of trussed roofing, trussed

partitioning and trussed beams were well

illustrated in books such as Francis Price’s

A Treatise on Carpentry

(1733), which were

produced in great numbers for the craft. The

demand for affordable technical literature

such as this demonstrates how 18th-century

craftsmen and professionals became engaged

in a quest for knowledge in the fields of

construction and architectural detailing.

Pattern books also conveyed fashionable

London’s architectural styles to the wealthy

in all parts of the kingdom and eventually had

the effect of regularising architectural style

in England through the gentrification of the

older properties in villages and towns.

CONSERVATION AND REPAIR

OF SOFTWOOD JOINERY

Conservation through repair is an ethic much

spoken of, but with regards to the repair of

external joinery of historical importance,

many people fail to appreciate just how positive

and permanent a well-executed repair can be.

One of the most common historic

external joinery elements is the box-framed

vertical sliding sash window. Neglected rotten

window frames are often seen as a burden and

simply replaced. However, they can usually

be repaired (the rot in softwood joinery is

actually often the result of poor maintenance

or previous sub-standard repairs), saving both

money and well-made historic joinery.

To encourage owners to repair (where

possible) rather than replace, it is necessary

for craftspeople and conservators to impart

confidence in the longevity of a well-repaired

item. This requires the relevant knowledge

to specify the correct repair materials and

expertise in the appropriate craft techniques

such as the scarfing and joining of new wood

to old.

Once a good repair is completed it

will serve for as long as the original item

is maintained and kept in working order.

Given that joinery items can almost always

be repaired, what is needed to achieve a

successful repair?

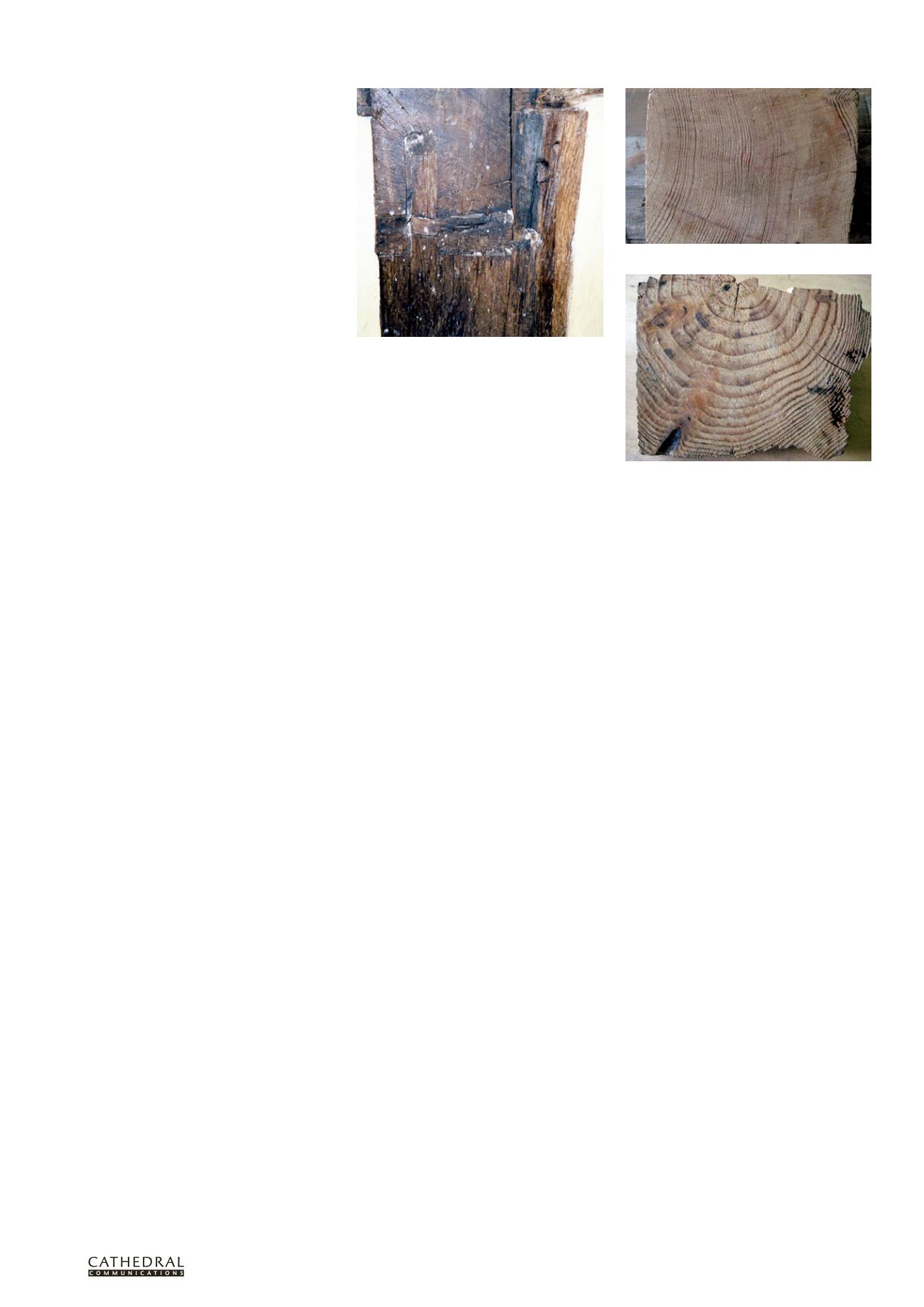

One of a pair of posts showing the thickened end of

the jowl, formed by the widening of the trunk close

to the ground. The end face of the wall plate can be

seen (upper left), fixed with a post-head tenon and

peg. The tie beam is just visible at the top of the post

(upper right). The paler wood at the right-hand edge

of the post is sapwood from the outer edge of the tree.

Slow-grown old-stand Baltic pine with typically tight grain

The base of a softwood post in a 17th-century timber

frame house in Rayleigh, Essex which was converted

from managed woodland timber: it shows faster

growth in the early years (closer to the centre), with

wide early wood growth rings and tighter late wood

being produced each year. The tighter growth rings

towards the outer edge of the tree indicate slower

growth before it was felled.