1 2 6

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

3.3

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

ME TAL ,

WOOD & GLASS

Quality of material

Much of our historic

joinery was constructed from wood that was

slow grown. This wood generally has a fine,

close-grained texture and, because much of it

was from old stands, it tends to be fairly clear

of knots and vertically grained, giving it good

durability and stability.

Today, managed softwood plantations

aim to produce timber as quickly and as

economically as possible. This faster grown

timber is not as durable as that from the mature

trees that were more common up to the start

of the 20th century. Much of the modern fast-

grown softwood will be used in construction

once it has been pressure impregnated with

preservatives. Generally this type of timber is

not suited to quality repairs of historic joinery.

The quality and closeness of grain of repair

timber should match that of the original as

closely as possible. This will reduce differential

movement at the junction of old and new wood.

The last remaining virgin forests in the

world are almost all protected, and timber

which matches the quality of that used in the

past can be difficult to find. Nevertheless, it is

still possible to obtain quality material from

legal and sustainable sources (see Defra’s

Timber Procurement Policy, 1 June 2013,

Due to the difficulties of fixing to end-

grain, some popular repair methods should be

avoided. In particular, some literature illustrates

the use of a 45-degree angle cut to join together

two pieces of joinery, such as extending the

stile of a frame. This amounts to almost end-

grain to end-grain fixing and has no life.

Preservative treatment

Due to the

generally less durable nature of redwood (but

not necessarily Douglas fir), the repair timber

may be specified as preservative-treated. If

this is the case, all the sections of wood that

are to be used in the repair would need to be

cut and fitted before being disassembled and

sent for treatment, so that all the surfaces

are properly protected from insect and fungi

invasion. Before fixing, it is essential that

the preservative-carrying fluids have fully

evaporated from the wood allowing it to be

glued. With or without preservative treatment,

when the repair is complete all the wood must

be primed and sealed, especially the end-grain.

Cost

Because the success of the repair

relies on good quality material, it is well worth

paying a little extra for it. Repairs are labour

intensive and when set against the labour

cost the extra expense of high quality repair

material is relatively small.

Longevity

Repairs undertaken with quality

materials and good craft practices become

part of the original structure. There are many

excellent carpenters and joiners who can, once

shown the methods, complete an extensive

repair to these historic elements while drawing

personal satisfaction from the process.

Recommended Reading

RG Albion,

Forest and Sea Power: The Timber

Problem of the Royal Navy 1652–1862

, Harvard

University Press, Cambridge (Mass), 1926, p182

J Bispham,

Wood Focus

, Institute of Wood

Science, issue 4, Spring 2001, pp4–5

HM Colvin (ed),

Building Accounts of King

Henry III

, Clarendon, Oxford, 1971

P Dollinger,

The German Hansa

, Macmillan,

London, 1964, p73

English Heritage,

Practical Building

Conservation: Timber

, Ashgate, Farnham, 2012

H Forrester,

Timber Framed Houses of Essex

,

Regency Press, London, 1976

O Rackham,

The Ancient Woodland of England:

The Woods of South-east Essex

, Rochford

District Council, Rochford, 1984

WG Simpson and CD Litton,

‘Dendrochronology in Cathedrals’

in

The

Archaeology of Cathedrals

, T Tatton-Brown

and J Munby (eds), Oxford University

Committee for Archaeology, no 42, 1996, p197

FH Titmuss,

Commercial Timbers of the World

,

Technical Press, London, 1965

JOSEPH BISPHAM

MSc PhD served a five-

year indentured apprenticeship (1962–1967)

as a carpenter and joiner. He has since built

up a business specialising in the repair and

conservation of historic timber buildings

and runs historic joinery repair courses for

the Society for the Protection of Ancient

Buildings and others. He lectures for a

number of organisations including the

Architectural Association and is a member

of the Institute of Wood Science.

available at

www.gov.uk) through established

timber merchants. Redwood (

Pinus Sylvestris

)

from Sweden, Finland or Russia is a good choice

for most joinery repairs. A good alternative

is Douglas fir (grade no 2, clear or better).

Selection is important and all repair timber

should be chosen and inspected piece by piece.

Moisture content is particularly important. It

is likely that the stocks sourced will have been

kiln dried. At the inspection stage moisture

readings should be taken of the historic joinery

in the zones of sound wood, especially in the

areas where the splicing of new to old is to take

place. The moisture content in the selected

repair timber and in the original wood should

correspond to within one or two per cent to

avoid subsequent movement.

Craft practice

Minimal intervention is a

key principle of good conservation practice.

However, in the case of joinery repairs some of

the sound wood must be removed so that the

new wood can be fixed to a sound material,

otherwise the repair will fail at the joint

between old and new.

Each repair will need to be assessed on its

own merit with regards to quality and the run

of the grain. Close inspection of the original

construction will reveal not only how it was

made but also the quality and species of wood

used. Any new sections of wood used in the

repairs need to be of the same dimensions and

matching profiles as the original joinery.

In joining a new section of wood to the

original, a method of repair should be chosen

so as to remove as little as possible of any

mouldings, and this may mean cutting into

original timber behind in order to preserve

the detail. The success of the repair relies on

joining the two pieces of wood together so that

new and old wood work together as a single

unit. The splice/scarf joint should be cut at

a shallow angle running along the grain of

the wood. The cut gives a larger surface area

with the run of the grain to glue the two faces

together. Wherever possible fixings should be

to the inner faces or sides. If exterior fixings are

required, stainless steel and wooden dowels for

tenons should be used.

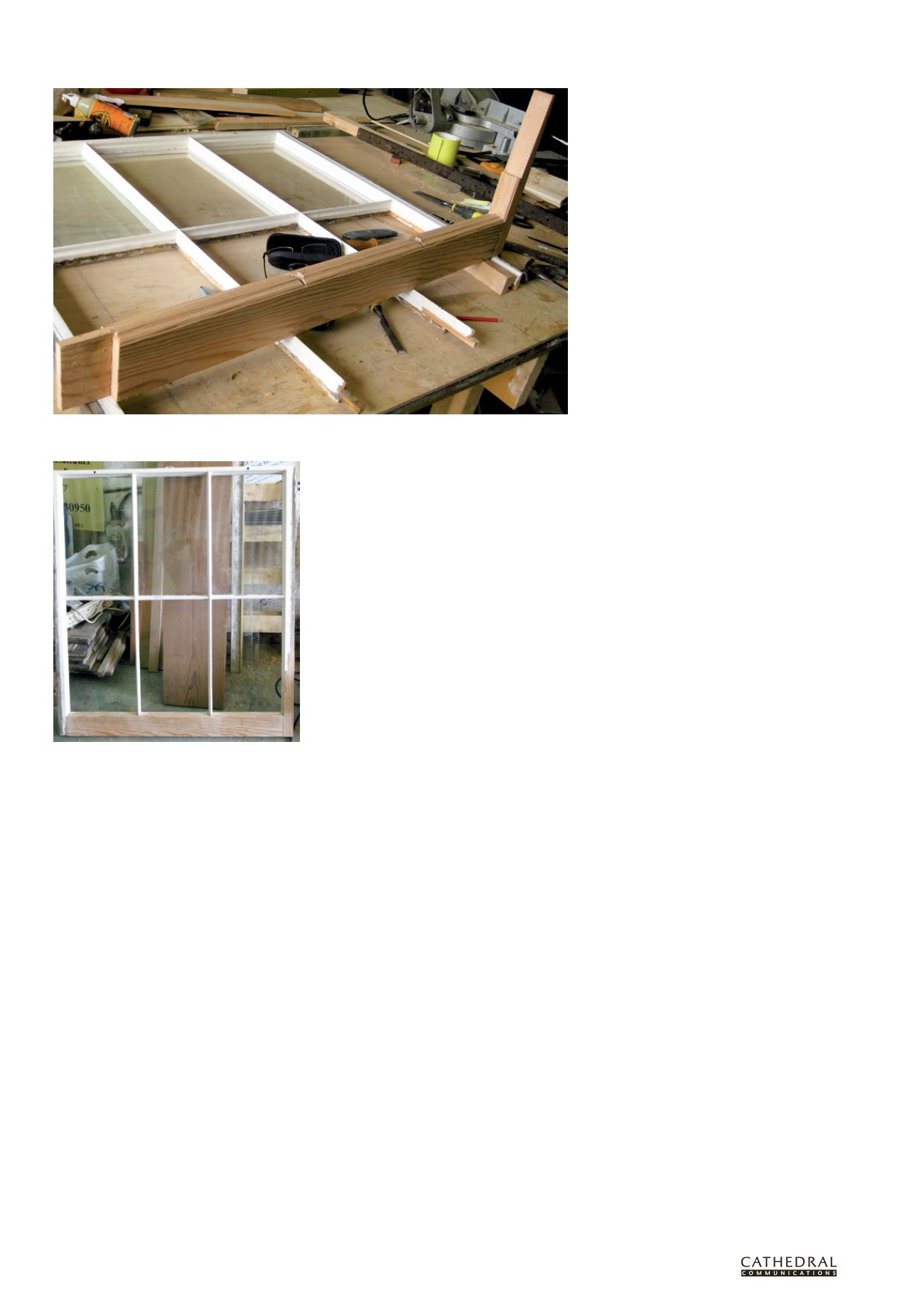

Repairing a sash with typical decay at the base: the new section of the stile was spliced to retain as much of the original

as possible. This late 18th-century window was made in pine and retained original hand-blown crown glass panes.

The repaired sash ready for priming and painting