T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

1 6 7

INTER IORS

5

applied to give the desired transparent

tint and to make subtle enhancements to

the design. The glazing layer was further

worked with additional diluted paints. It

could also be partially wiped out with a rag,

a

‘

veining horn

’

(a rolled soft leather cloth

or a piece of wood with a rounded end) or a

natural sponge to modify its appearance.

Binding media

In common with both 19th century

architectural painting practice and easel

painting techniques paints for marbling were

made from pigments ground into a drying

oil and diluted with turpentine. Normally,

linseed oil was used as it was capable of

forming a relatively quick drying and strong

paint film, especially in combination with

siccative pigments, such as lead white.

Victorian treatise recommend, again as was

common practice, the addition of a little

boiled oil or driers if slow drying (non-

siccative) pigments, such as mortuum caput

or vine black were to be used. Some authors

suggest the use of poppy oil with white

pigments such as zinc white, as it was less

prone to yellowing than linseed. However, in

well-lit rooms or exterior work, linseed oil

was recommended as best for all whites as it

formed more durable paint.

Water colour may also have been exploited

to produce effects not easily obtainable in oil,

often in the preliminary stages, and the work

completed in an oil medium, with perhaps a

final glaze in watercolour.

Pigments

The pigments used were those generally

available to the Victorian artist, while sensible

economies were made in order to respect

the size of

faux

marble panels to be prepared

and the consequent costs. For example, in

recommending pigments for

Br

è

che violette

Van der Burg lists zinc white, black, ochre,

chrome-orange, red

mortuum caput

(a

purplish iron oxide), ultramarine blue and

organic red lake pigments. He goes on to say:

The painter knows very well that lake

fades away by a strong light and that

the colour which is of great importance

in this marble should be durable. We

therefore advise to paint a work, which

is much exposed to the sunlight, with

caput mortuum as much as possible,

and to use the fading (organic lake)

colour as little as possible, though it

cannot entirely be dispensed with

…

Varnishes and waxes

Varnishes were applied to intensify the

appearance of the paint layers and to provide

a degree of protection to the delicate surface

finish. By the 19th century spirit varnishes

produced by dissolving tree resins, such as

dammar or mastic, in solvent were widely

used. Traditionally varnishes are clear,

however, their appearance can be modified by

the addition of pigments and other materials.

The inclusion of wax, for example, produces a

less glossy varnish film. Natural waxes were

also used to give a saturated polished look to

marbled surfaces.

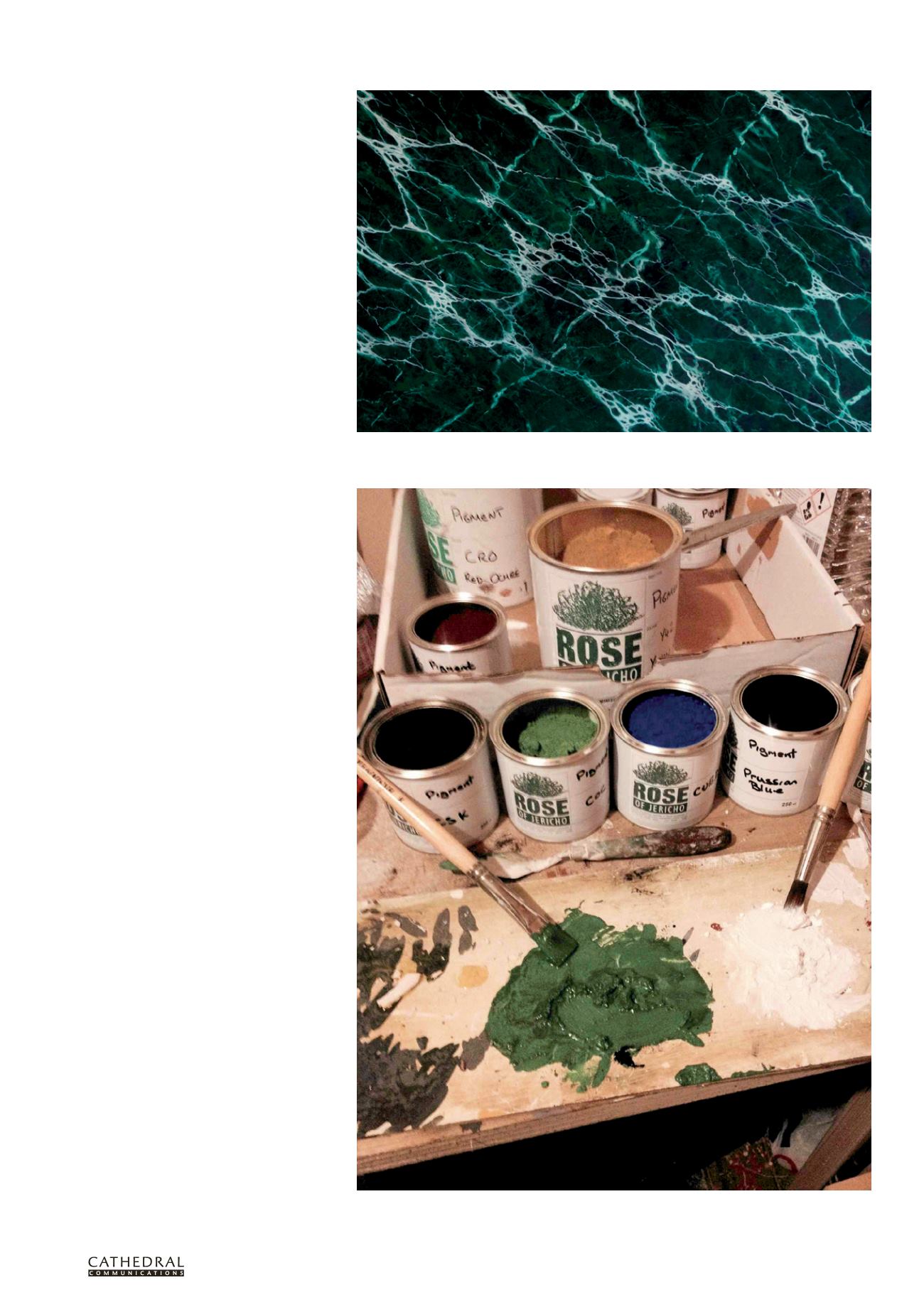

A recently painted example of marbling in imitation of green

vert de mer

marble, which owes its name to the

form of its veining which suggests the waves of the sea. This was an expensive marble and was often imitated

during the 19th century.

Dry pigments are ground into linseed oil to form a paint paste that is then diluted with turpentine for application.