T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

5 3

2

BUI LDING CONTRACTORS

CONCRETE REPAIRS

Traditional methods and

like-for-like materials

DAVID FARRELL AND CHRIS WOOD

W

HERE HISTORIC

fabric requires

conservation, damaged material

is usually repaired in situ, and

any new material and details required are

expected to match the existing on a like-for

like basis wherever possible. However, where

concrete is concerned the European standard

Products and Systems for the Protection and

Repair of Concrete Structures

(EN1504-5:2013)

recommends that all repair mixes should

come ready-bagged from certified factories.

Almost all materials certified under this

standard are modern ‘concrete repair mortars’

not concrete. While their use on historic

buildings and structures may be justified in

some instances, like-for-like repairs will often

perform at least as well and any decision to

vary the materials must be based on a sound

understanding of the options.

BACKGROUND

Historic concrete includes reinforced concrete

(RC) and bulk (non-reinforced) concrete (BC);

a material which has been widely used for

military facilities in the past. RC generally

suffers from deterioration (mainly carbonation

and chloride attack) of the concrete which

subsequently allows the steel reinforcements

to corrode; this results in cracking and

delamination of the concrete ‘cover’. BC

tends to suffer more from ground movement

and differential expansion and contraction

which causes cracking and slippage of larger

sections of concrete. Different pours of

BC (laid down at different times) sometimes

become detached from each other resulting in

movement. Both types of concrete suffer from

weathering by pollutants in combination with

rain and mould/algal growth which mar their

appearance.

Like-for-like patch repairs to concrete

have been carried out in the past but many of

these are now failing for a variety of reasons.

Some repairs were too shallow and did not

adequately address the underlying corrosion

of the reinforcements, or they were not

‘mechanically bonded’ to the host concrete

(feather edging, for example, may result in

cracking and shrinkage). There have also been

difficulties matching the colour and texture

of the original material. These problems,

along with the desire for easy and quick repair

methods suitable for unskilled labour, led to

the development of modern repair mortars

which are now widely used for repairing

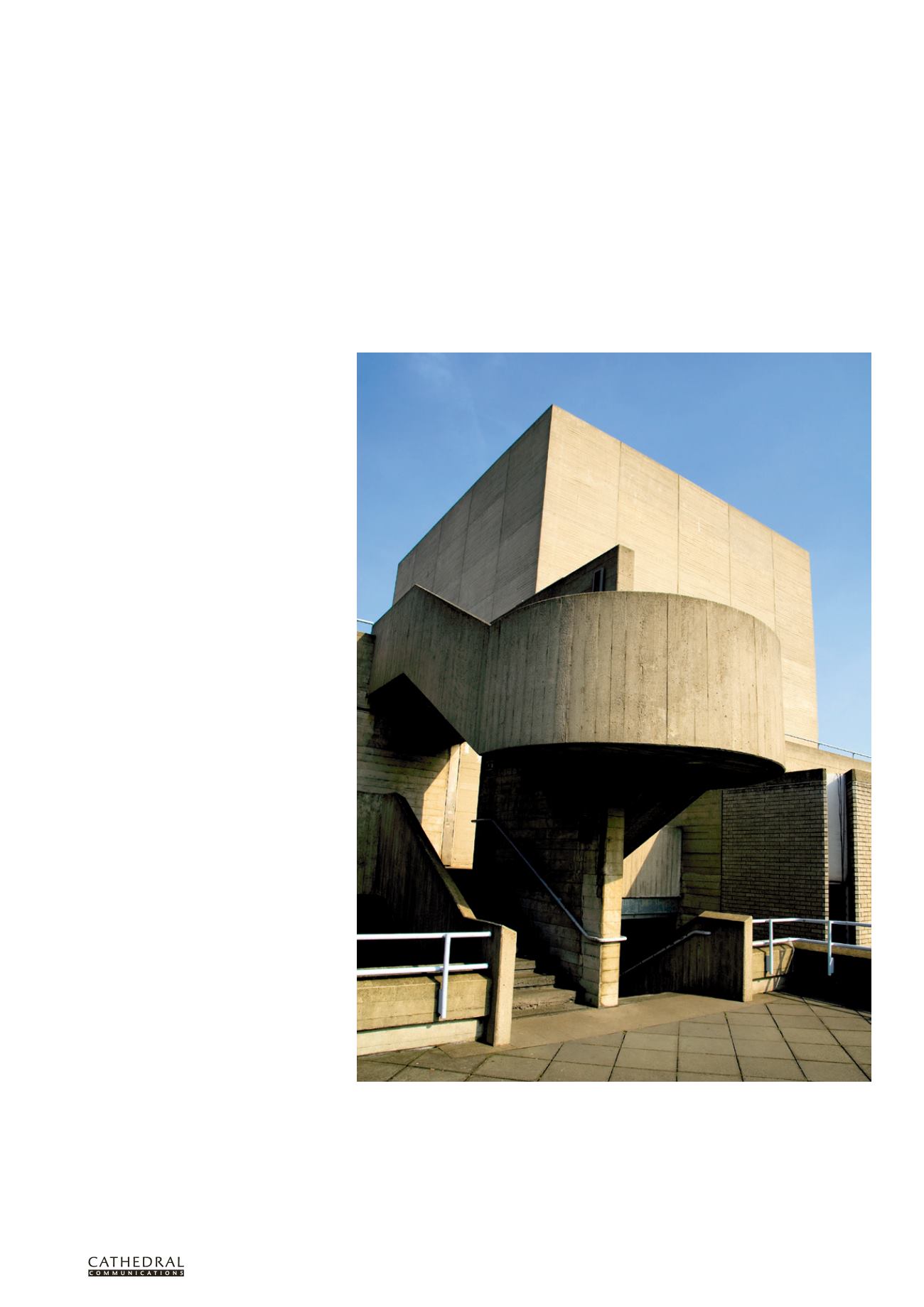

Figure 1 A staircase at the National Theatre, London (Photo: NAES, iStock.com)

concrete. Many of these contain polymer

modified components which can be applied as

thin layers to delaminated surfaces and adhere

strongly to the host material. These repair

mortars are not popular with the conservation

industry as they introduce different materials

and do not weather-in to match. Their

longevity is also uncertain when used in

combination with the parent concrete.

The adaptation of traditional types of

repair in England has been growing since

2001 when the church of St John and St Mary