5 4

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

2

BUI LDING CONTRACTORS

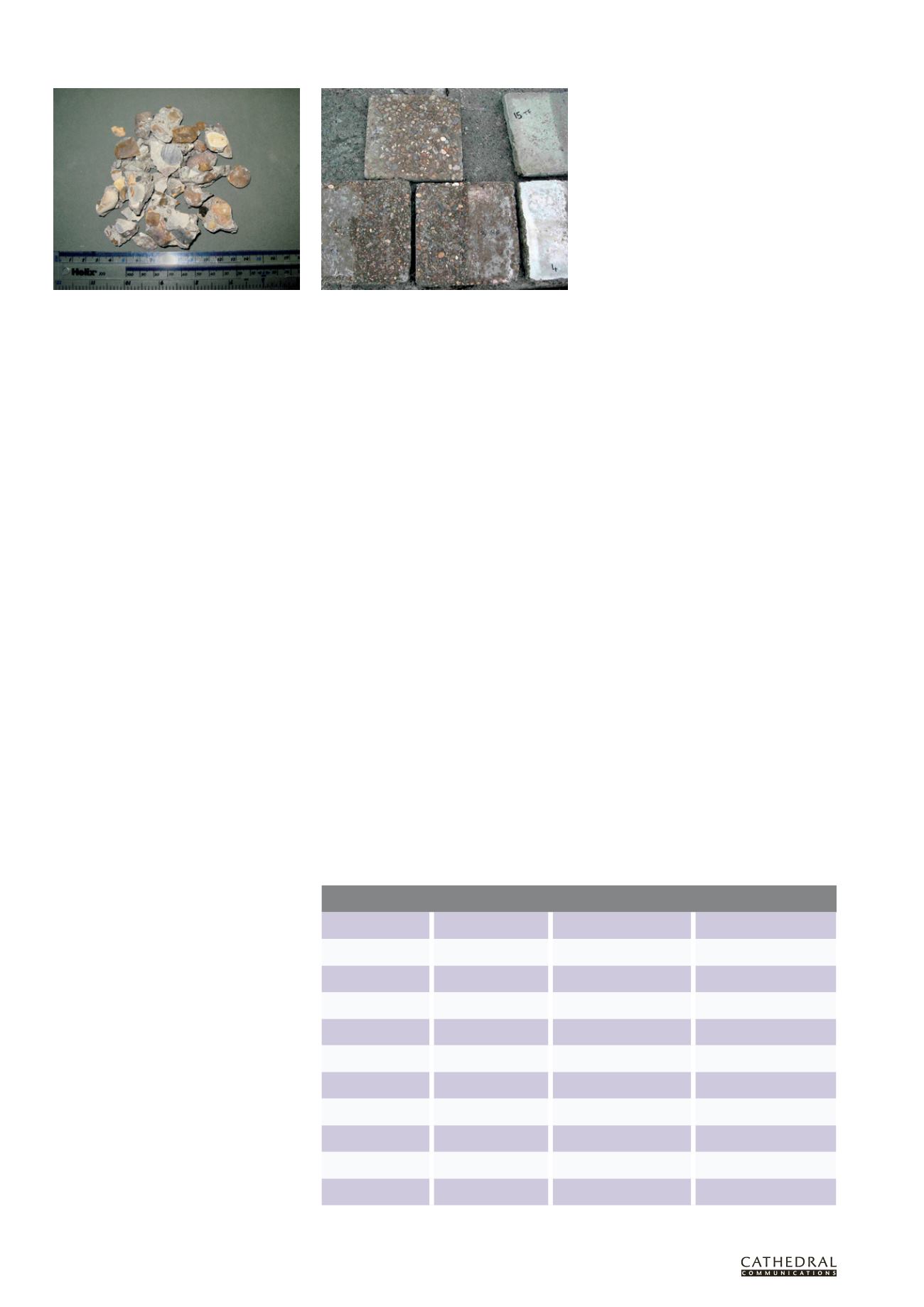

Figure 3 Concrete test flags using different mixes

and with retardants applied to one side only. Half

the surfaces were wire brushed after early breakout

(12 hours).

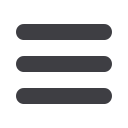

Figure 2 Sample of concrete from the National

Theatre exhibiting naturally round and broken

aggregate, with centimetre measure

Magdalene, Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire

was successfully repaired and conserved.

Additional trials and testing were carried

out at Tynemouth Priory Coastal Battery

(bulk concrete structures dating back to the

1880s) and the Listening Mirrors, Dungeness

(reinforced concrete dating from the 1930s).

Other developments and testing carried out in

this period are discussed in English Heritage’s

Practical Building Conservation: Concrete

(see Recommended Reading).

Several ongoing repair projects where

like-for-like repairs are being implemented are

referred to below. However the main focus of

this article is the National Theatre, London

where an initial investigation of the concrete

was carried out and methods and materials

were specified for traditional repairs. These

were further improved by the contractor and

many smaller scale repairs are currently being

carried out.

THE NATIONAL THEATRE

Built in 1976, mainly of steel reinforced

concrete, the National Theatre is an iconic

building on London’s south bank which is

now listed Grade II*. Its concrete is generally

in good condition but over the years it

has suffered some deterioration. In places

the steel reinforcements had insufficient

cover causing the concrete to crack or

spall, while in others cracks were caused

by thermal movement and subsidence.

Mechanical damage had also occurred where

fixtures have been added and removed.

The theatre is currently undergoing

alteration and its concrete is being repaired.

Because of its historic status the repairs are

being carried out on a like-for-like basis as

far as possible. More modern methods and

materials are only being employed where this

is not possible, or where a different approach is

sure to result in a better repair.

To replicate the original mix accurately,

documentary sources were checked first, then

samples were taken for analysis.

Documentary assessment

The only

documented evidence of the original

constituents of the concrete used was the ‘Bill

of Quantities for Superstructure to National

Theatre (Phase 2)’ which was dated 1970, six

years before it was built. From this it was

concluded that the ‘white’ concrete forming

the external board-marked (wood grain),

bush hammered and fair-faced concrete was

originally intended to comprise the following:

• 80% Snowcrete (WPC) and 20%

ordinary Portland cement (OPC)

• Leighton Buzzard sand as fine aggregate

• Newmarket flint (¾” to ⅜”) as large

aggregate (angular or rounded

crushed rock) – specified at the time

to be obtained from Allen Newport

in Fordham, Cambridgeshire.

• The mix was generally described as

between 1:8 and 1:3.3 (by dry weight)

cement to total aggregate. However,

other sections in the book describe their

ratio as being between 1:7 and 1:4.

Visual assessment

A view of the

aggregate from a fair-faced core sample

is shown in Figure 2. This shows the large

aggregate to be mainly rounded stones, much

of it broken. The size distribution of the large

aggregate was 11–22mm, corresponding with

the ⅜” to ¾” specified. Particles of the sand

were separated out from the concrete and

measured. Typical fine aggregate diameters of

0.3–0.8mm were found.

Geological assessment

Further analysis

of aggregate from the broken sample was

carried out at Aberdeen University by Natalie

Healy, a postgraduate researcher whose report

is summarised below:

The samples of Newmarket Flint

aggregate consist of concrete and

poorly sorted quartz and feldspathic

grain (sandy) matrix derived from

TRIAL MIXES FOR THE NT TEST SLABS

Mix No. and Ratio Cement

Sand

Aggregate

1 (1:2:3)

80:20

WPC:OPCLeighton Buzzard white 10mm Newmarket flint

2 (1:2:3)

80:20

WPC:OPCLeighton Buzzard white 20mm Newmarket flint

3 (1:2:3)

80:20

WPC:OPCLeighton Buzzard yellow 10mm Newmarket flint

4 (1:2:3)

80:20

WPC:OPCLeighton Buzzard yellow 20mm Newmarket flint

5 (1:2:3)

100% WPC

Leighton Buzzard white 10mm Newmarket flint

6 (1:2:3)

100% WPC

Leighton Buzzard yellow 10mm Newmarket flint

7 (1:2:4)

80:20

WPC:OPCLeighton Buzzard white 10mm Newmarket flint

8 (1:2:4)

80:20

WPC:OPCLeighton Buzzard yellow 10mm Newmarket flint

9 (1:2:4)

100% WPC

Leighton Buzzard white 10mm Newmarket flint

10 (1:2:4)

100% WPC

Leighton Buzzard yellow 10mm Newmarket flint

an Arkosic sandstone. The sample

contains rounded clasts of various

sizes and lithologies including flint,

shelly debris and chalk and few clasts

of crystalline quartz. Clast lithology

has been identified using standard

mineral identification techniques

including Moh’s scale of hardness.

Clast types identified include:

• Predominantly orange and brown

and few grey clasts of silica rich,

cryptocrytalline flint identified by

a hardness of 7 and characteristic

conchoidal fracturing. Clast

size ranges from 3mm-20mm.

• Clasts of silicified indeterminate

Pectin shells (scallops) ranging

in size from 5mm-<10mm.

• Few clasts of iron stained

translucent crystalline quartz.

• Few clasts of fine grained, well

cemented chalk identified

by a hardness of 3.

• Rare clasts of black, lustrous,

soft organic material possibly

produced from fossilised wood.

Sandy matrix

The concrete matrix comprises poorly

sorted rounded grains of quartz,

feldspar, lithics and few green coloured

grains of the mineral glauconite.

Matrix sandstones may be sourced

from the overlying Upper Greensand

Formation which outcrops nearby

Fordham.

MATCHING THE ORIGINAL CONCRETE

The lack of availability of the original

constituents can often present problems

for the conservation of historic concrete.

Early concrete aggregates (pre-1960s) were

normally sourced from local suppliers which

were themselves supplied by local quarries,

but many have since been ‘worked out’ or

closed. So the first task was to see if these

constituents were still available:

Cements

– White Portland Cement

(WPC) is ubiquitous, although it is likely to