T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

1 2 9

3.4

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

EXTERNAL WORKS

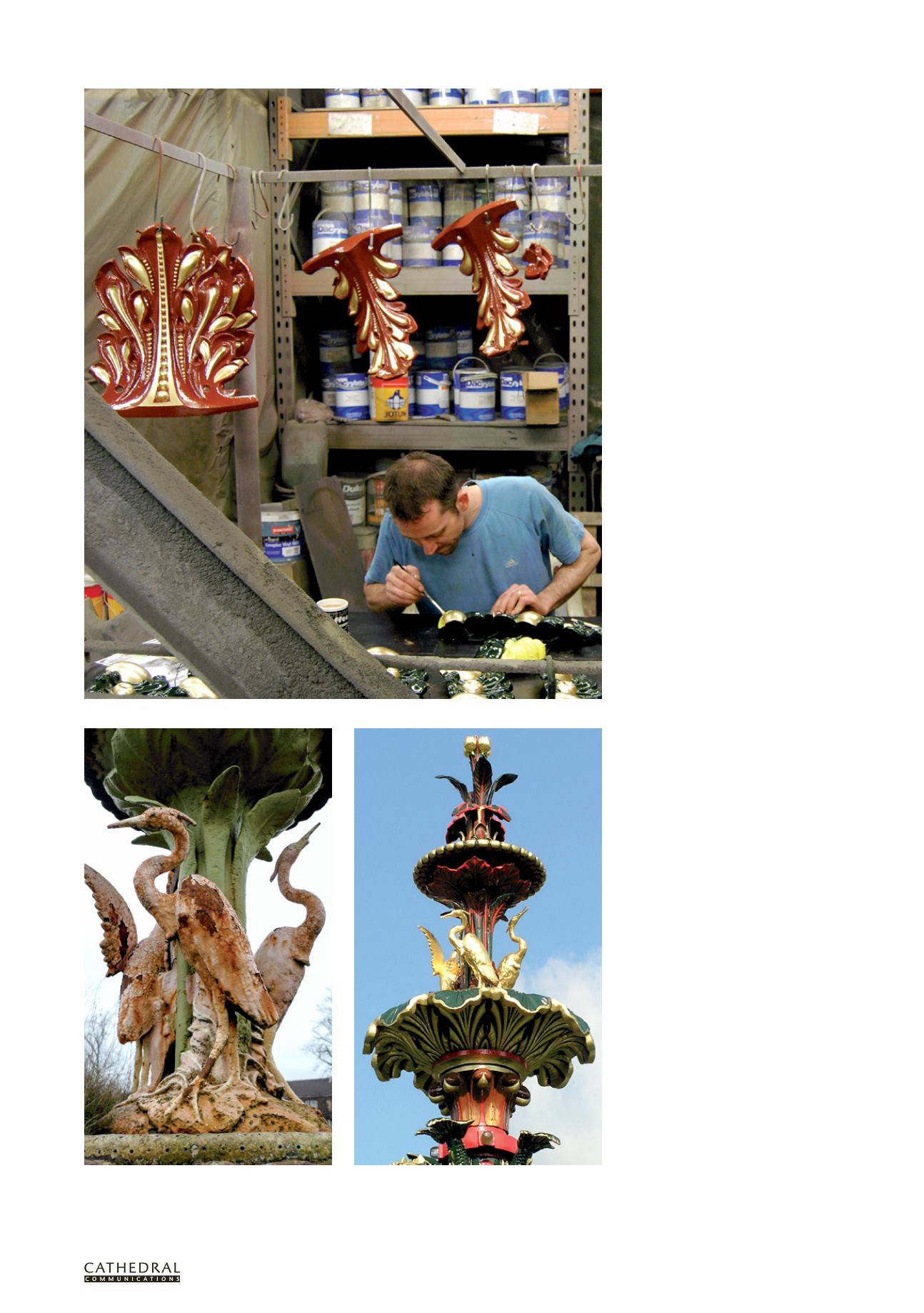

furnish several fascinating case studies but

the focus of this article is the re-creation of

the original colour scheme designed by Daniel

Cottier (1837–1891), an artist and designer

born in Glasgow.

Cottier is best known for his fine stained

and painted glass work, as well as interior

decoration. He worked with architects such

as Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson and William

Leiper, who in turn often commissioned work

from the top ornamental iron-founders of the

day, George Smith & Co’s Sun Foundry and

Walter MacFarlane’s Saracen Foundry.

Research

The restoration of the fountain took over

a year. However, prior to the physical

restoration the team had to undertake

extensive research into the history of the

fountain and its colour scheme. This included

referring to the rather frustrating descriptions

detailed in the inauguration booklet of 1868:

The decorations of the central fountain,

like those of the iron gateways,

lamps and railings, are of the richest

character. The main fountain is, at

the base, toned with deep sombre

tints appropriate to iron structures

and gradually rises into a series of

variegated bronzes that bring out the

respective ornamental parts of the

structure with additional effect. The

base of the foundation, wherever the

structure would allow of its appropriate

introduction, has had piquancy added

to it by small bits of brilliant colouring

which take away entirely any feeling of

heaviness, and look very pretty.

Consultant conservation engineer James

Mitchell took particular interest in finding the

right colour, paint and glazing solution for the

fountain, given the importance of the original

colour scheme. Daniel Lea, production

manager with Lost Art, led the restoration

works and spent time experimenting to find

the best approach to applying the complex

coatings. The process was long and arduous

and required over 100 paint samples and

hours of testing supplemented by an initial

paint study carried out by Historic Scotland

in 2006.

Restoration

The fountain was dismantled and moved

to a conservation workshop, where a

long period of repair and preparation

of individual pieces was needed before

the final coatings could be applied.

Due to the condition of the structure it

was essential to clean it back to bare metal.

There is much debate about the best way to

clean and (equally importantly) seal bared

cast iron. In the 19th century new iron

castings were often doused with linseed

oil while still very hot, which prevented

‘gingering’ or flash rusting before it could

be painted. As the paints were then largely

linseed oil-based the first coat of red

lead suffused nicely with the oiled iron

surface. This practice fell out of favour as

coatings became more ‘sophisticated’.

Today, when coatings are removed by

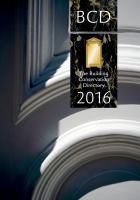

Repainting work under way in the conservation workshop

To ensure that the original colour scheme was re-created as accurately as possible, the herons and the tulip to the

top of the structure were finished in gold leaf. This should retain its finish for longer than gold paints, which tend to

discolour over time due to the effects of UV light.