T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

1 6 1

INTER IORS

5

dominance of classicism as the complicated

designs of rococo France or gothic England

became achievable without the need for wood

carvers or marble masons.

Possibly as a hangover from 17th-

century practice, it became customary to

employ colour and gilding to elevate cheaper

materials to a higher status in decorative

schemes. Varied colour starts to become

more prevalent, initially in the form of tints

that required less pigment for ceilings and

gradually in stronger tones for wall schemes.

By the reign of George III the scene was

set for the great neo-classical architects,

Chambers, Wyatt and Adam, to introduce

intricate and subtly contrasting areas of

colour into wall and ceiling decoration. By

publishing their views and their designs

the Adam brothers dominated the field

of decoration, then and for posterity. The

colouring of the interiors of ancient buildings

was evidently their starting point. Over time

they adapted the palette to suit the times they

lived in as well as the availability of pigments.

Pale greens and blues became their default

colours but it can be argued that, after stony

off-whites, these were the default colours for

the reigns of all four Georges.

By the end of the century advances in

manufacturing, the processing of paint

ingredients and an increase in affluence had

liberated the choice and use of colour in

interiors. Fashion could play a greater part

but social status remained a key determinant.

By George IV’s regency the house painter

was once again called upon to simulate costly

natural materials like marble or bronze as

well as to render a wide range of colour.

Contemporary colourman’s catalogues give an

insight into the cost and prevalence of colours

and their suitability for use in oil or distemper.

We have inherited a vast and varied range

of buildings from the Georgian period, from

great country houses to humble cottages.

In decorating many of them we are now

concerned with their historical significance

(often they are listed) and what is appropriate

within the confines of modern taste, budget

and practicality. The first thing to remember

is that historic buildings are an information

resource which helps to unlock our

understanding of the past. We will not be able

to read all of it and so it is important to allow

future generations the widest possible access

by preserving paint history and retaining

period detail. Reversibility should underpin

the design of alterations and avoidance of

waste should determine what is retained.

The redecoration of a historic interior has to

start with these details – their restoration or

reinstatement – the architecture can be our

guide as to what is the appropriate period of a

building’s evolution to return to modern use.

When it comes to introducing colour we need

to be aware of the sweep of history, but to start

from the basics.

Colour is rendered in an interior by three

principal means: the use of construction

materials in their natural state, dyed yarn

or cloth, and pigmented paints. This is as

true today as it was in the reigns of the four

Georges. Unlike today, however, the only

materials available in the 18th century had to

be derived from minerals, plants or animals.

Their availability determined their use.

Scarce pigments and rare dyes soon became

associated with the wealthiest, most powerful

and most sacred. Tropical hardwoods and

imported marbles were the preserve of the

rich. At the other end of the spectrum, earth

pigments and native materials gave rise to the

common colours.

It is not possible to disassociate the

status of the owner with the appearance of

interior decoration during this period. A poor

household could only opt for a limited palette

rendered with inexpensive paint binders, while

the affluent owner could choose to construct

his rooms with oak or exotic veneers, cut stone

or statuary marble, flock papers or imported

silks and their painters could employ the

costliest pigments suspended in linseed oil.

It is important to remember that dramatic

advances in academic research and paint

analysis have been made in recent years. At

the same time the price differential between

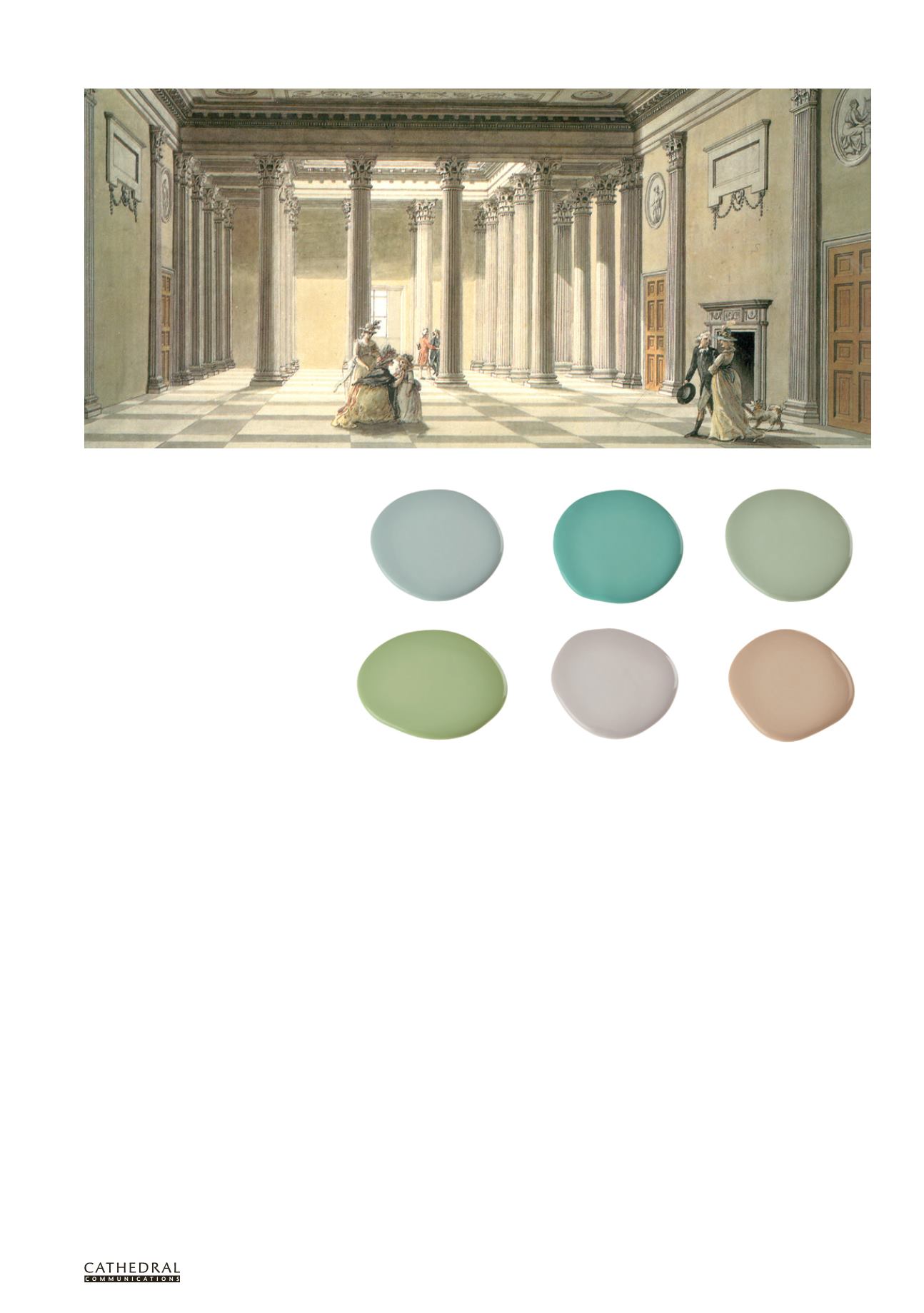

George III colours: a greater variety of colours became affordable in the second half of the 18th century as

illustrated by these examples, again given names from the period.

Sky Blue

Vert de Mer

Celadon

Pomona

Laylock

Jonquil

The Hall at Purbrook, Hampshire, designed by Sir Robert Taylor. This watercolour, painted by Thomas Malton in the 1790s, shows the continued use of stone colour for

halls well into George III’s reign.