1 6 0

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

INTER IORS

5

owner in its decorative arms and the other

ornamentation was frequently in the form of

relief and statuary. Paintings, when employed,

were often set into the walls as part of the

room’s architecture. Much the most common

decorative scheme for this room would have

been a stone white colour mixed with earth

pigments and perhaps carbon black. In terms

of democratising interior decoration this

proved to be the most influential room in the

house. Its colour scheme proclaimed gentility

and learning but its execution employed the

cheapest pigments. This could be emulated

right down the social scale. As a default this

approach endured throughout the Georgian

period. In many ways it endures to this day –

the communal spaces of high status buildings

are still often in a tinted white and the popular

predilection in selecting a colour is still to

choose a variant of white tinted with the

equivalent of earth pigments.

Early in the century fitting out of an

interior was generally done with full timber

panelling or just wainscot (a panelled dado

in effect). It was usual to use softwood if it

was to be painted and rooms that were to be

hung with paper or fabric would be battened

out above the wainscot and lined with canvas.

This meant that colour was mainly rendered

in oil paint allowing for deeper colouring

as, unlike the opaque white medium of a

limewash or distemper, linseed oil was clear,

meaning that the pigment went further.

Nevertheless it could take up to five coats to

achieve a solid colour and so lighter colours

remained the choice for economy.

Early in the Georgian period, strong

colour was usually introduced in dyed

cloth – damasks, wools and velvets. When

these fabrics were used for walling their

cost indicated a room of importance. This

could be a private or a public room but was

seen and used by a very select audience.

All the time the eye was to be delighted

but the mind was intended to understand

the status and cultured standing of the

patron. The dyes employed in Paris or Genoa

underlined this, blues, greens, reds and

yellows all signalled rarity and richness.

Following their use by the wealthy, the

producers of cheaper alternatives adopted

these colours for everything from flock paper

to wall paint. Luxury defined the palette

and was a function of cost. Colours became

emblematic as was the case in easel painting.

As the 18th century progressed, timber

wainscot gave way to plasterwork. While it

had been customary to paint panelling in

a uniform colour from skirting to cornice,

the arrival of applied wooden mouldings

on flat plastered walls allowed distempers

to be used on the flats. Using distemper

to decorate could allow for further cost

savings – minimal pigment was required to

produce an off-white oil paint for the trim,

and effective use of pigment with binders

meant greater coverage and therefore fewer

coats, for the walls. Picking-out required more

time but was a good way to emphasise the

skill of the ‘stuccadore’ and gradually plaster

ornamentation became the dominant vehicle

for styling a room. It spelled the end of the

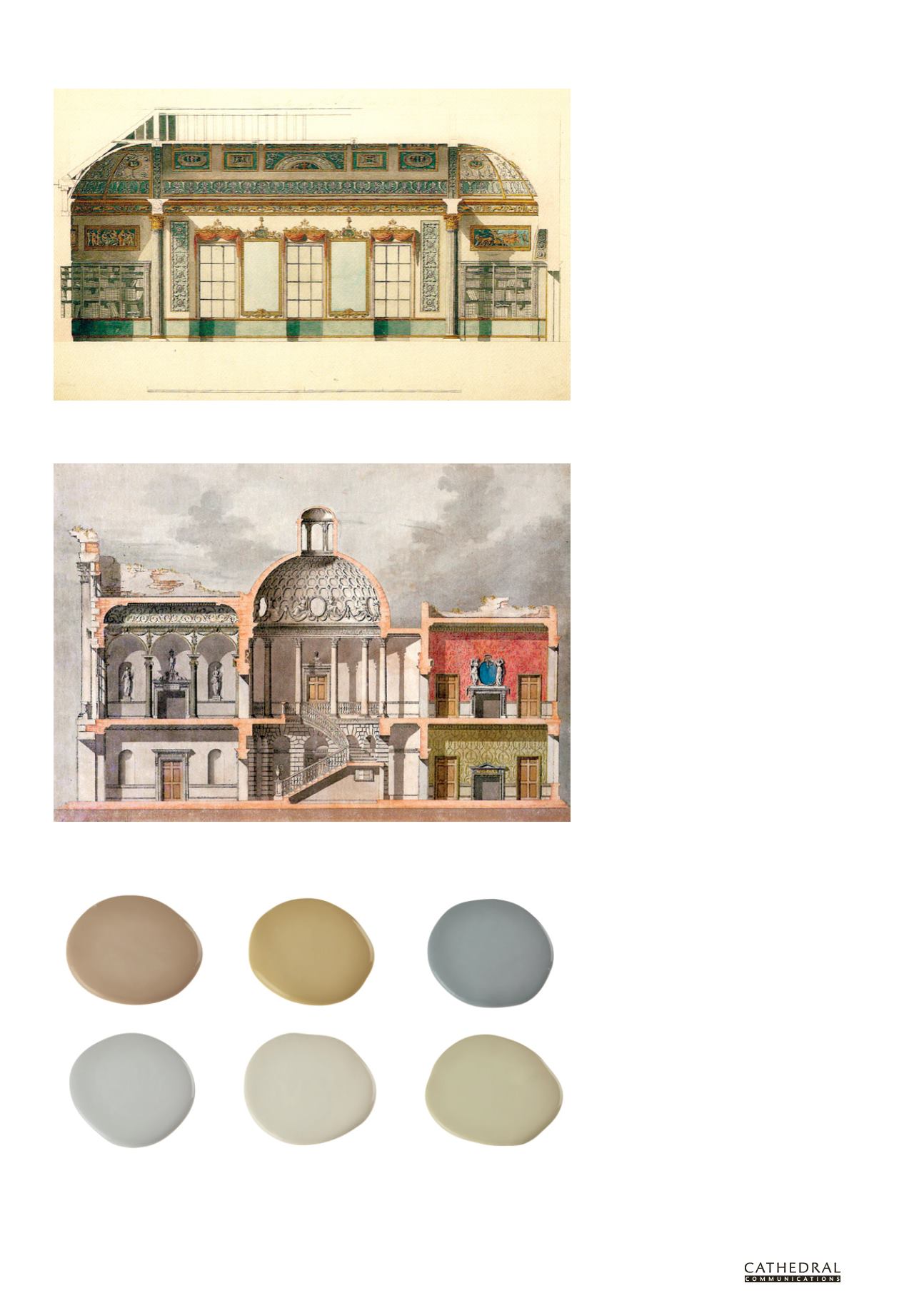

George I and II colours: known as ‘common colours’, historic paint specialists still make them today. The names

used here are taken from old colourman’s catalogues.

Clove

Lute

Inferior Grey

Wash Stop

Tinted White

Paris Grey

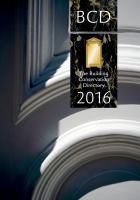

Robert Adam’s 1767 proposal for decorating the library at Kenwood House. Recent paint analysis has shown

that Adam’s proposal for gilding was not carried out until the second scheme and in the first scheme the

allocation of colour was changed.

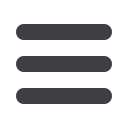

Unexecuted design for York House, London by Sir William Chambers (1759): this and similar examples of

coloured cross sections clearly show the hierarchy of colour used in the Georgian period. Stone or common

colours are used in the communal spaces like the hall and stair and richer colours, some with pattern, adorn

the family rooms.