1 6 2

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

INTER IORS

5

construction materials has narrowed and, in

the case of paints, mainstream manufacturers

now offer thousands of colours at price parity.

The visual record of the Georgian period

should also be treated with care. Portraits and

room views are a vital source, but of course

they tend to show affluent or even imaginary

interiors. Similarly, coloured proposals

made by the comparatively new profession of

architect in this period are also to be treated

as just ‘proposals’ unless paint analysis can

prove the schemes were executed.

PAINT INVESTIGATIONS

Among the most important contributors

to modern research in this field are John

Cornforth, Ian Bristow and Patrick Baty,

who have all greatly added to the body

of knowledge about how colour was

made and deployed in historic interiors.

Their written works are invaluable and

should be consulted by anyone keen

to develop a good understanding of

interior colour, particularly paints.

Paint analysis in John Cornforth’s day

(the mid to late 20th century) was a matter

for a scientific laboratory and he (with John

Fowler) tended to rely on paint scrapes. As

a result their findings cannot be seen to be

that reliable. They did, however, interest

themselves in the practicalities of the painters’

and upholsterers’ trades and their resulting

insights were a useful step in a direction that

has been superseded by what is thought of as a

more scientific approach these days.

Paint analysis now conforms to an

industry ‘best practice’ and involves high

magnification observation and chemical

testing. It can reveal the chronology of

surviving paint layers fairly reliably, it can

assess colour and it can identify pigments

and binders. Typically, a modern equivalent is

then provided for the colour match required

– usually the ‘original’ scheme. This will be

a specially prepared sample or an industry

equivalent matched using a colour chart such

as the NCS (Natural Colour System). The

assumption is that this colour will be mixed

in a modern paint which, since the 2010 VOC

regulations, has essentially meant a plastic

emulsion or eggshell (based on an acrylic or

alkyd binder). In other words, we learn a great

deal about the paint layers but in the cases

where a historic recreation is required, we

usually ignore what we have learnt about the

binder, the solvent and even the origin of the

pigment, in order to recreate the colour using

commercial dyes and petro-chemical binders.

RESTORATION – THE IMPORTANCE OF

THE MEDIA

For those seeking to restore a period

property authentically this is important.

Many decisions arise, all of which have

cost implications and all of which affect

the appearance of our work as well as the

architectural and historic significance of the

surviving fabric. Choices may include the use

of timber or MDF, stone or cast dressings,

marble or resin, vinyl or leather, joiner-made

window or manufactured UPVC. In most

cases the correct choice will be obvious since

the vast majority of decisions are made from

the standpoint that the ‘real thing’ will be used

wherever possible. However, in 30 years I have

seldom been asked to engage in this debate

when it comes to paint. Plastic is fine as long

as the colour is right!

Paint is a building product, it is there

to protect and to decorate. Period buildings

tend to have dynamic substrates that

require breathability to prevent moisture

becoming trapped, leading to decay. The

character of a period building relies on the

detailing of the components that make up

the rooms: their line, their execution and

their surface texture. The paint film strongly

influences the amount of light reflected

from surfaces and hence their appearance.

Traditional paints were made with

ground pigment in a medium based on lime

or chalk (with a binder such as casein or

size), or linseed oil and lead carbonate. Most

modern paints are universally made with the

same crude oil derived binder and are tinted

with colorants. The appearance rendered is

different and the way they behave in light

is very different. More importantly, their

porosity is vastly different and they cannot

equal the breathability of traditional coatings.

Logically, the type of finish and the choice

of medium is even more important than the

choice of colour. Is cloth or wallpaper right,

or should it be a paint colour applied directly

to the substrate? And if so how should that

paint be made? To follow historic precedent

the probability is that rooms in all but the

most important Georgian houses would have

been painted with earth pigments in a white

base. This gives an aesthetic that works well

in a period and modern way, but we are also

lucky enough to have a great range of other

cost-effective wall coverings and colours and

so we tend not to restrict ourselves to the

common colours for these (typically Grade II

listed) buildings.

The right approach in every case is to

pay attention to tonality rather than colour

because this will ensure that you choose from

the right palette. To arrive at the right tonality

for historic interiors is easily achieved if you

start with the right range of pigments. Artists

and house painters have shared a palette for

centuries and I offer my selection to act as a

summation to this brief exploration of colour:

• earth pigments: yellow ochre,

raw umber and red ochre

• mineral pigments: chrome yellow, Prussian

blue, ultramarine, viridian, black and white

• organic pigments: alizarin and carmine.

Further Information

P Baty, ‘The Hierarchy of Colour in Eighteenth

Century Decoration’, 2011

(http://bc-url.

com/colours)

IC Bristow,

Architectural Colour in British

Interiors 1615–1840

, Yale University Press,

New Haven and London, 1996

IC Bristow,

Interior House-Painting Colours

and Technology 1615–1840

, Yale University

Press, New Haven and London, 1996

N Eastaugh et al,

Pigment Compendium:

A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of

Historical Pigments

, Routledge, London,

2008

J Fowler and J Cornforth,

English Decoration

in the 18th Century

, Barrie & Jenkins,

London, 1983

C Saumarez Smith,

Eighteenth-century

Decoration: Design and the Domestic

Interior in England

, Weidenfeld and

Nicolson, London, 1993

EDWARD BULMER

specialises in the

redecoration of historic buildings as well

as the creation of historic schemes for new

buildings. His company Edward Bulmer Pots

of Paint now offers a range of paints made

with traditional materials and coloured with

powdered pigments (see page 135).

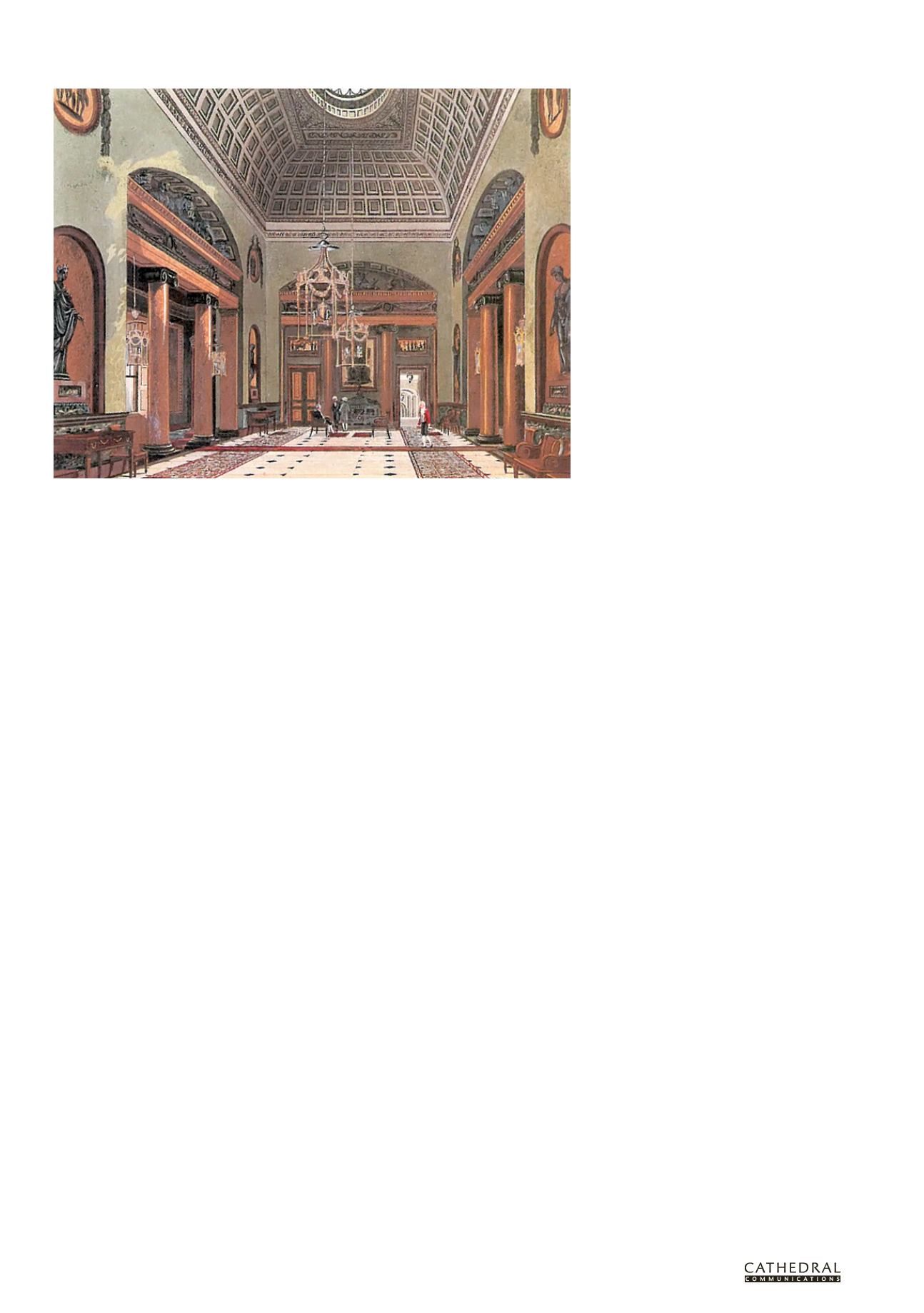

The Hall at Carlton House after redecoration in 1804: the columns were in scagliola but the rest of the

decoration was painted in imitation of bronze, Sienna and Verde Antique offset by a granite green on the walls.