Cleaning St Paul's

Conservation Technology and Practice

David Odgers

The huge task of cleaning St Paul's was divided into four phases and is scheduled for completion in March 2005. Now that it is some two thirds complete, it is possible to give an idea of how the work has provided such technical and practical challenges for the design team and a team of over 20 conservators and craftspeople. The extent of the work can be summarised as follows:

- cleaning the stonework

- stripping and redecorating the plaster vaults

- carrying out conservation repairs to damaged stonework

- selectively cutting out and renewing cement pointing

- removing redundant and superfluous fittings

- carving enriched mouldings where not carved

- gilding ungilded mouldings within otherwise gilded areas

- cleaning and conserving existing painted and gilded surfaces

- cleaning and conserving the Thornhill paintings in the dome and the upper cone

- recreating the (overpainted) Thornhill scheme in the tambour

- repainting and patinating the walls of the Whispering Gallery

- cleaning and conserving mosaic surfaces

- cleaning ironwork generally

- cleaning and refurbishing timberwork of doors and screens

- cleaning the monuments, both freestanding and wall mounted

- cleaning the windows to allow in more light

One of the most important factors is to cope with the sheer scale of the building and the challenge of providing access to all areas. Scaffolding is absolutely crucial to any project but perhaps even more so in a place such as St Paul's with all its curves, niches and domes. Add to these design complications the need to minimise any impact on services, musical activities, visitor flows and the need to carry out the erection and dismantling during the night, and then it is possible to understand the complexities of the process. Having started with a single contractor, there have at times been three different scaffolding contractors on site providing access to separate, albeit adjacent, areas. It has been crucial to ensure that the actual scaffolders understand the nature of the work and the need for conservators to get close to the surfaces they are working on.

|

| The scaffold, which was designed by Ray Gould, provides light-weight access to the dome and tambour, and can be rotated as each section is completed. |

One of the most challenging aspects of the project has been the construction of an access platform under the dome. The Cathedral Fabric Archive contains some delightful and detailed drawings of the scaffold provided to this area in the middle of the 19th century.

Owing more to the riggers of the tall ships from the London docks, it depicts restorers (complete with lunchboxes) standing on small platforms suspended on ropes from holes in the dome and being lowered by a man on the end of the rope standing on the Whispering Gallery.

Health and safety legislation has moved on somewhat since then and the scaffolding designer (Ray Gold) spent over two years perfecting a lightweight and manoeuvrable scaffolding that is now in position and provides access to all areas of the dome, cone and tambour. This responds to a requirement from the design team that the Whispering Gallery must remain open to visitors, and that the Thornhill dome must be as open as possible to view during the project.

Effectively, one quarter of the dome is scaffolded and the construction is held in place by a cruciform frame with legs set on the seat of the Whispering Gallery and the whole suspended from the lantern. When work on one quadrant is complete, the whole scaffold can be rotated to the next quadrant.

As access becomes available to each area, a detailed study can be made of the various materials encountered. However, before this can happen, a very thick and very black layer of dust has had to be removed from all the surfaces. Sometimes this can be up to 15mm thick and may represent the accumulation from over 100 years. The dirt layers are being carefully removed by soft brushes and vacuum cleaners and, during this process, interesting discoveries are being made - maybe an old tool left by earlier craftsmen, graffiti from the original masons or clear evidence of previous interventions. These features and the condition of the surfaces are all being recorded.

STONEWORK

|

|

| Arte Mundit (top), being applied with a spray to the masonry and, (above) being removed, leaving a much cleaner surface. (below), fine carving is then finished by hand. |

|

Following the cleaning trials carried out by Deborah Carthy, a latex cleaning technique developed by Eddy Dewitte at the Institut Royale du Patrimonie Artistique in Brussels was chosen as being the one that most effectively removed the more tenacious surface accretions from the stonework.

A version of this poultice, known by the trade name 'Arte Mundit', was specially formulated for the Portland stone and the type of dirt found at St Paul's. This dirt is a complex collection of materials resulting from factors such as the polluted London atmosphere, gas lighting, darkening of the surface due to remnants of the original oil paint left in the pores, the caustic and abrasive methods used for paint removal and applied surface treatments.

Essentially, the latex contains a chemical called EDTA (ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid, a chelating agent which breaks down organic binders). Although this has been used as a cleaning agent in conservation for many years, it has been found to etch limestone and marble when applied as an aqueous solution. By binding EDTA into a latex medium, the contact time is restricted to the curing period of the latex which, at most, is two hours. Thus the dirt is removed and, as has been shown by various scanning techniques, the surface is left cleaned and undamaged.

As the poultice is only suitable for stone, all other areas are protected prior to application. All gilding, mosaics, applied decoration, light fittings, wood and metalwork are carefully taped up and wrapped in polythene so that there is no danger of the latex coming into contact with these other materials.

The manufacturers of the Arte Mundit latex poultice (FTB Restoration) devised a machine capable of spraying the liquid latex onto the stone to a thickness of between 2 and 3mm. By varying the nozzle size they could ensure that the material was evenly applied to both flat areas of stonework and to the deepest undercuts of the carving. The latex cures at the surface very quickly but is left for 24 hours to set completely. It can then be peeled off and the loosened dirt either comes off bound into the poultice or can be washed off the stonework with clean water and bristle brushes.

There were one or two teething problems early in the project and, in order to minimise any potential risk, the spraying is carried out at night. Repeated tests have shown that there is no risk to either operatives, the public or members of the cathedral staff. The cleaned stonework has the pale lightness of Portland stone without taking on the homogeneity of 'overcleaned' stone. It has also allowed the delicacy and art of the extraordinary wealth of carving to have become decipherable again.

One unfortunate side effect of cleaning stonework is to reveal all its imperfections. At St Paul's there are areas of damp ingress where the stone has been stained by decades of moisture movement; there are large amounts of pointing carried out in a mortar mix (often cementitious) which had been designed to match the colour of the dirty stone; and there are areas of almost blanket grout splashing which, grey in colour, are more visually distracting than actually damaging. It seems strange that craftsmen who carried out very complex structural repairs did not take more care to wash off the grout.

These problems are being dealt with in a number of ways. If any pointing is loose, it is removed and replaced with a limebased mortar. Grey cement mortar (mostly found at low level) is removed if this can be accomplished without damage to the stone, and then repointing is carried out in lime mortar.

The worst of the grout runs can be picked off the surface but in many instances the grout layer is too thin to make this possible and so a limewash is being used to soften the visual impact. A yellow oily resinous pointing had also been used in some areas and this repeatedly stained through any applied limewash, so, where possible, the resinous pointing is scraped back and a lime mortar is used to replace it. Holes and voids are filled with a lime mortar to match the stone.

GILDING

Gilding in the cathedral is more plentiful than intended in the original designs and has been applied to different areas at various times. Most of the gilding was found to be well adhered and in good condition but very dirty. It was cleaned using a variety of methods such as warm water, 'V&A mix' (water and white spirit) and diluted solutions of ammonia.

New gilding was applied in certain instances - most notably in two areas; the north transept and the Whispering Gallery railings. During the war an incendiary bomb fell through the north transept roof causing significant damage. When restored after the war, the decorative rim of the saucer dome was left ungilded in accordance with repair principles for new work to be clearly recognisable. Over the years the imbalance with the gilded rim of the south transept was felt to be unsatisfactory aesthetically, and so the decision was made to gild the rim in the north transept to match.

Close inspection of the railings around the Whispering Gallery showed the gilding here to be very worn. Moreover, there were 12 layers of paint and gilding on the ironwork ranging from original grey to the first of several Victorian applications of gold. Following consolidation of the existing layer, the railings were regilded but to a level that did not give too strident an appearance.

MOSAICS

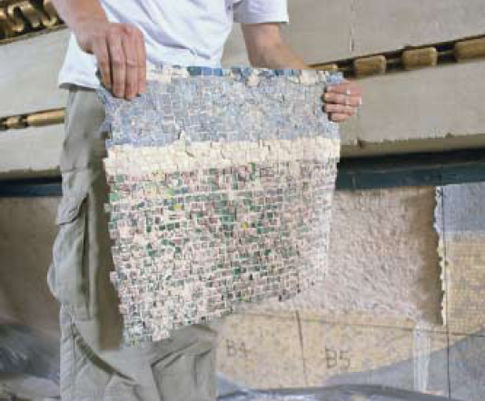

Perhaps the most interesting element of the work has been the conservation of the mosaics. Although it is possible that Wren wanted the dome to be covered in mosaics, it seems more likely that he would have wanted a simple painted architectural treatment. In either case A section of mosaic during removal for rebacking in the workshop his wishes were overruled by the Dean and Chapter who commissioned Thornhill to create his famous painting. Later on, in the 19th century, large areas of mosaics were also introduced over a period of over 40 years. The mosaic schemes are of two very different types.

|

| A section of mosaic during removal for rebacking in the workshop |

In the overhanging panels beneath the Whispering Gallery, the workshop of Antonio Salviati created eight works between 1864 and 1892. These were executed using the indirect method whereby sections of the mosaic are made up on a 'cartoon' in a workshop before being transferred to a ready prepared lime mortar bed. The individual ceramic pieces, or 'tesserae', are close fitting and flat. Inevitably, with such a method there are potential problems in lack of adhesion.

This was certainly the case with St Luke which was removed and re-attached in 1925. When access to the panel of St Mark was available in March of this year, it was discovered that much of the mosaic was separated from the stone substrate and may have been held in place only with a length of angle iron secured into the stone at the top. The proximity of the organ may also have played a part in causing vibration that gradually loosened the mosaic.

After careful study by Trevor Caley Associates Limited, it was concluded that the mosaic panel needed to be taken down and so, in a reverse procedure of its installation, the mosaic has been removed in small sections to a workshop for re-backing. The revealed mortar was very crumbly and showed signs of having dried too quickly.

Another type of mosaic is also prevalent in the quarter- and semi-domes as well as all along the choir and in the vaulting of the choir aisles. These were designed by Richmond and executed by Powell's of Whitefriars between 1891 and 1898. The irregular glass tesserae were applied directly onto an oil mastic mortar and set at varying angles which, because of the reflected light, imparts a more lively appearance. Unfortunately, the mastic mortar hardens and curls with age so that certain sections had become detached from the stone substrate and, in two areas of the quarter domes, had fallen altogether. These sections were recreated and detached areas were pinned and grouted.

All of the mosaics of both styles were painstakingly cleaned using cotton wool swabs, first with warm water and then with de-ionised water, although slightly different techniques were adopted for the Salviati panels where coloured mortars susceptible to moisture had been used to disguise the joints between the sections.

The work on the tambour and dome is only just beginning, but more challenges await the architect and conservators involved in that part of the project. Throughout the two and a half years of this wide ranging programme, the communication and understanding between client, contractor, Surveyor to the Fabric and all the many other parties involved in the functioning of the cathedral, has been of the highest order and has resulted in a project that has already successfully transformed the interior.