1 6 2

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

INTERIORS

5

graining was used continually as a decorative

technique over the 200 years under

consideration, although its popularity grew

and waned according to the architectural

taste of the day. Generally speaking it was

considered fashionable during the Baroque

period at the end of the 17th and beginning of

the 18th centuries, but fell into decline during

the Palladian and neo-classical periods of

architecture. It found favour once again in

the Regency period in the opening decades

of the 19th century and remained a strong

decorative force until the reforming influence

of individuals such as John Ruskin and AWN

Pugin in the middle of the century declared

such imitative work a sham. Regardless,

boards and dado rails. The property had been

built to the designs of Charles Steuart in 1785,

but it underwent extensive redecoration for

the second Lord Berwick 17 years later, in

1812-13. Lord Berwick had recently married

and was spending large sums of money

to bring his property in line with current

London Regency architectural tastes. This

was reflected in the lavish style of decoration

he employed in the Octagon Room, which

was adapted for use as a study. The extent of

the alterations also contributed to Berwick’s

downfall, as his expenditure at Attingham

far exceeded his fortune and he was made

bankrupt in 1827.

Initial analysis indicated the presence of

a complex manipulated scheme consisting of

multiple opaque and translucent red layers as

well as varnish coatings applied over a black

ground. There was some evidence to suggest

that hard particles of grit had been added to

this base coat to lend it variety and texture.

The scheme was probably intended as an

imitation of rosewood. The analysis, coupled

with uncovering trials, allowed for the

scheme to be successfully reproduced by the

National Trust, lending the room back some

of its original Regency opulence.

Despite the popularity of graining at

this time, the technique was by no means

ubiquitous, and the absence of graining in

a building can indicate a specific aesthetic

choice and approach to interior decoration.

This eschewing of imitative painting

techniques was evident in the early 18th-

century Quaker meeting houses in both

Ringwood, Hampshire and Bristol. In

its place plain solid colours were used to

decorate the interior woodwork.

Another omission of particular interest

can be found in the much later example of

William Morris’s Red House in Bexleyheath,

London, which was designed by Philip Webb

in 1859–60. A riot of colour, patterned

decoration, wall paintings and textiles were

identified as forming part of the property’s

initial interior design. However, not one

example of original graining was pinpointed.

In many ways Red House was the testing

ground where Morris experimented with

design ideas that were to later find form in his

commercial work in the closing decades of

the 19th century. His avoidance of imitative

techniques such as graining was, for Morris

and his cohorts, a statement of intent.

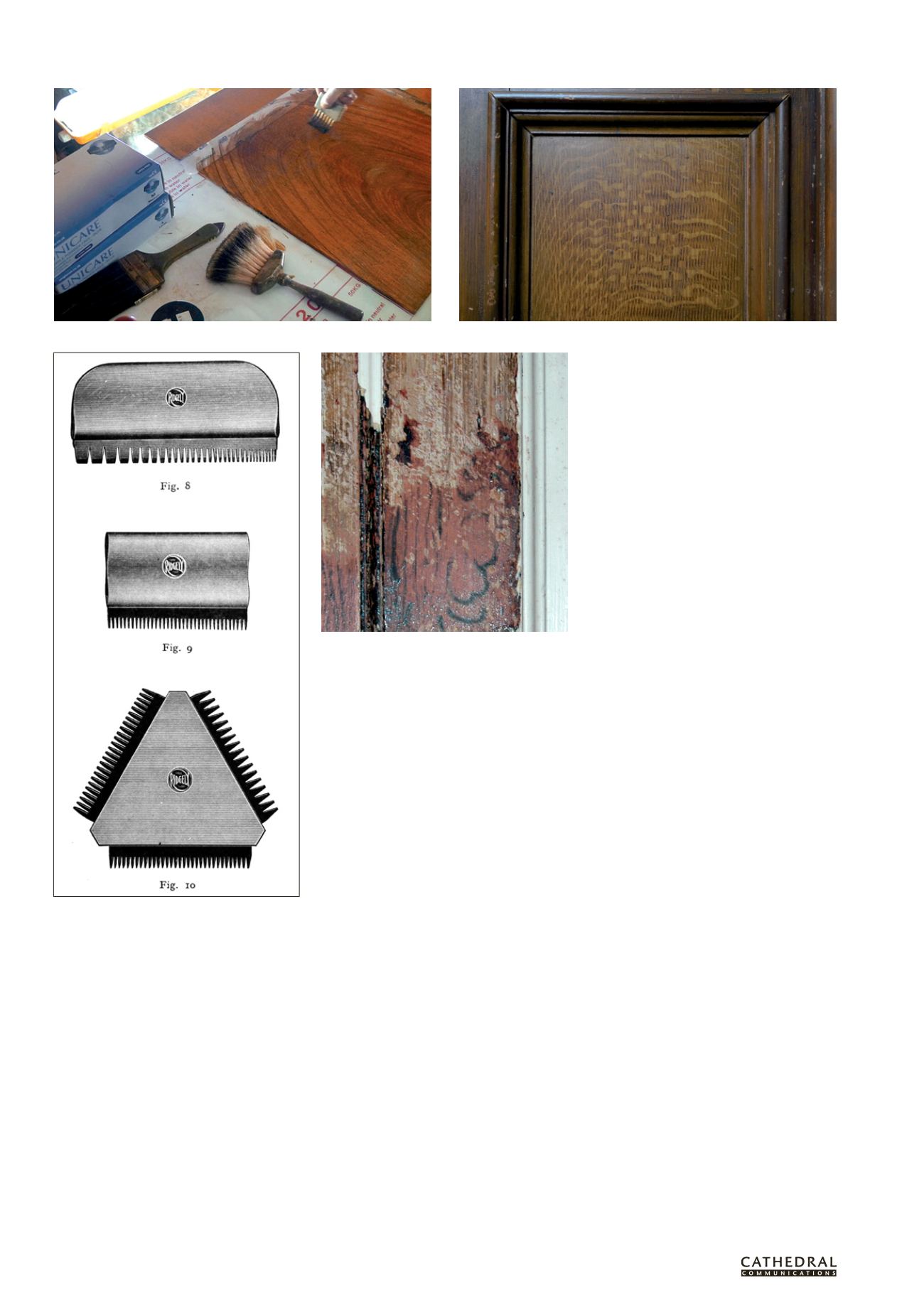

Graining tools (Photo: Hare & Humphreys Ltd)

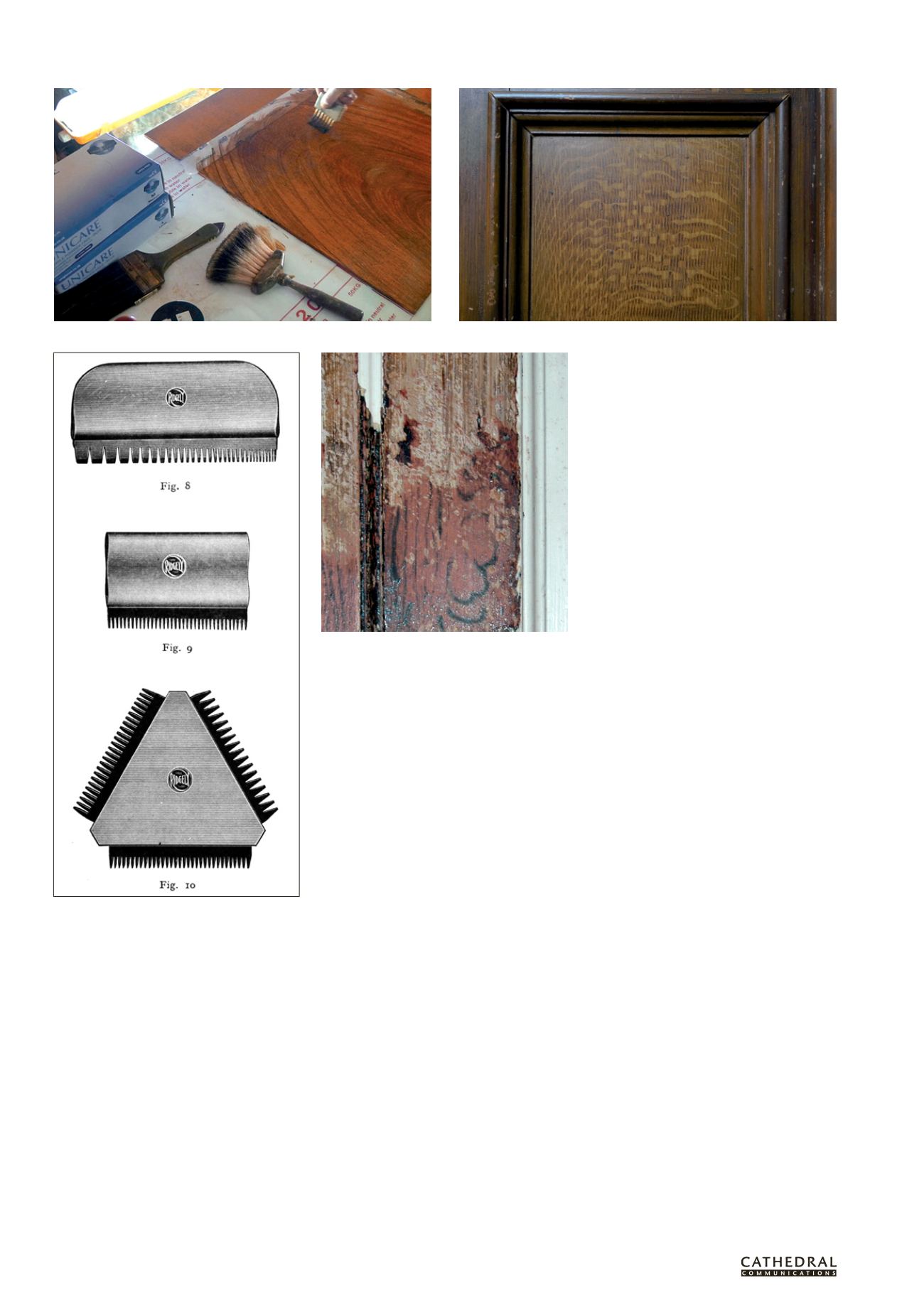

Victorian oak graining showing the use of ‘lights’ running across the grain

Oak graining uncovered during the investigation of the

dairy complex at Kenwood House, Hampstead: the

dairy was built in 1795 as a picturesque eye catcher

on the brow of the hill to the west of the main house,

hence the high quality of its finishes (Photo: Jane

Davies Conservation, by courtesy of English Heritage)

Early 20th century ‘Ridgely’ graining combs

illustrated in

The Modern Painter and Decorator

(see

Recommended Reading

)

graining continued to be used in many

buildings, but it does not appear to have

recovered critical acceptance until the last

quarter of the century.

It is interesting to note that the

popularity of some woods over others also

changed during the period.

HOW GRAINING WAS USED

At a time when softwood was almost always

painted, the principal aim of graining was

not only to provide pattern and richness to

an interior, but to give an impression that a

more expensive timber had been employed.

The most commonly imitated wood was oak,

no doubt because of the long tradition of

its use in Britain and the familiarity of its

figuring. Other popular hardwoods included

walnut and mahogany, which could convey

an even greater degree of luxury.

As the decorator’s manuals of the day

suggest, the techniques involved in the

execution of graining could be relatively

simple or they could involve the intricate

application of many strata.

One such elaborate graining decoration

was identified on all the joinery in the

Octagon Room at Attingham Park,

Shropshire, including the entrance door

and its architrave, the window cases and

architraves, built-in bookcases, skirting