T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

7 5

3.1

STRUCTURE & FABRIC :

ROOFING

REPAIRING CLAY BUILDINGS

and CUMBRIA’S CLAY DABBINS

PETER MESSENGER

A

LTHOUGH THIS

article focuses on the

revival of interest in clay buildings in

Cumbria, the repair and maintenance

issues which are discussed here are relevant to

all variants of earth construction in the UK..

Most clay dabbins, as they are known

locally, are quite modest structures but some

have survived remarkably well (right). Nearly

all are rendered and it is often impossible to

detect that a building is built of clay until

the building starts to decay. When render is

removed or falls off, or a clay wall collapses

(sometimes without warning) the structure

becomes visible. The horizontal clay layers,

each of which is usually 50–150mm deep, are

separated by thin layers of straw which are

only millimetres thick.

Examples of this form of construction

have been found in Wales and Scotland but

they only appear to exist in England on the

Solway Plain. They were once very common on

both sides of the Solway but building clearance

and improvement on the Scottish side has

reduced this to three surviving examples.

In Cumbria several hundred examples have

survived, dating from the 16th to the 19th

centuries, and include cottages, farmhouses

and farm buildings, many of which are cruck

framed (overleaf, centre). Numbers have been

diminishing over the last century or longer, as

the use of unburnt clay as a building material

eventually ceased and the craftsmen capable of

maintaining these buildings died out.

BASIC CARE

In temperate climates the main cause of decay

in earth building is water penetration. It is

important to protect the top and bottom of any

earth wall and to ensure that any treatment

applied to the interior or exterior of a clay wall

is breathable. When water does occasionally

find a way in, it can dry out naturally as long as

the water vapour can reach the surface of the

wall and evaporate. If there are signs of water

penetration these need to be investigated and

treated. Cement render is a common cause of

damp problems as it tends to prevent water

vapour from reaching the surface. Unable to

dry out, the wall begins to deteriorate and, if

the problem is not addressed, it will eventually

fail, often quite dramatically.

If a clay wall is very damp and it is

cement rendered, care should be taken when

investigating the state of the clay underneath

as, in the worst cases, saturated clay can

literally pour out. Removing patches of

render from the upper wall first and gradually

working down to the plinth is the preferred

course of action. If the clay wall is excessively

damp and soft then it should be left to dry

out for several days. Once this section is dry

then the removal of render can resume. Once

the wall has dried out the strength of the clay

wall will gradually return and it will then be

possible to address any other problems that

have been uncovered.

The most appropriate finish for a clay

wall is the traditional solution of using either

an earth or lime render or a limewash. No

impervious coatings of any description should

ever be used.

Protecting the top of the wall with deep

eaves helps to keep the top and much of the

face of the wall dry. If this is not possible then

adequately sized, well maintained guttering

and downpipes are paramount. Most clay

buildings have a stone plinth on which the

clay wall is set, and in dabbins this is generally

about half a metre high; if this is free of

vegetation and there is good drainage around

the building this should prevent any damp

attacking the base of the clay wall.

THE CLAY DABBIN PROJECT

A survey carried out for English Heritage by

Oxford Archaeology North in 2006 identified

just over 300 surviving clay dabbin structures

in Cumbria. A significant number were in a

poor condition and although it was possible to

give advice on how repairs should be carried

out, not a single suitable contractor could be

found in the region.

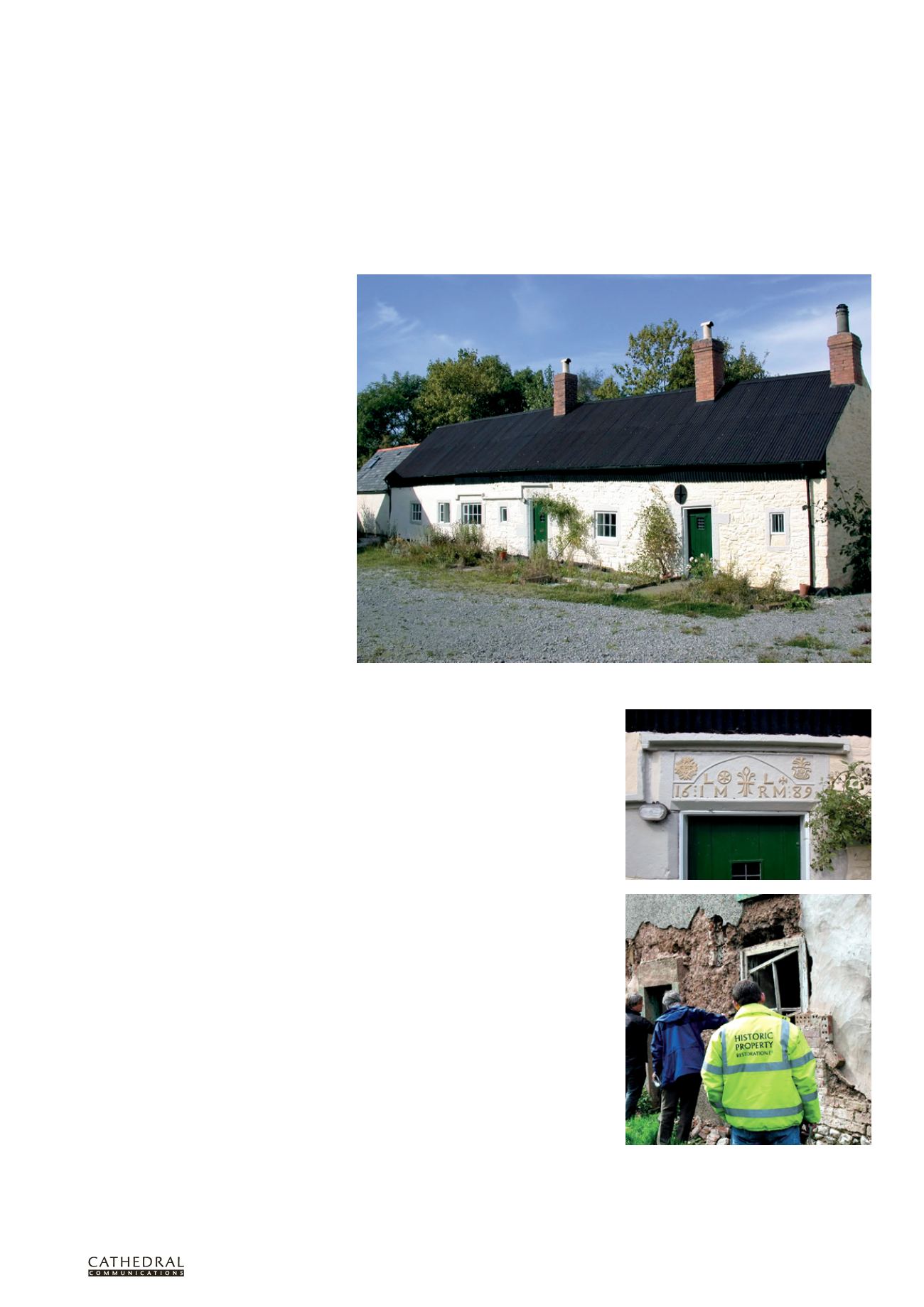

Traditional long-house at Durdar, Cumbria, which has since been thatched and, below, the long-house’s

1689 date stone

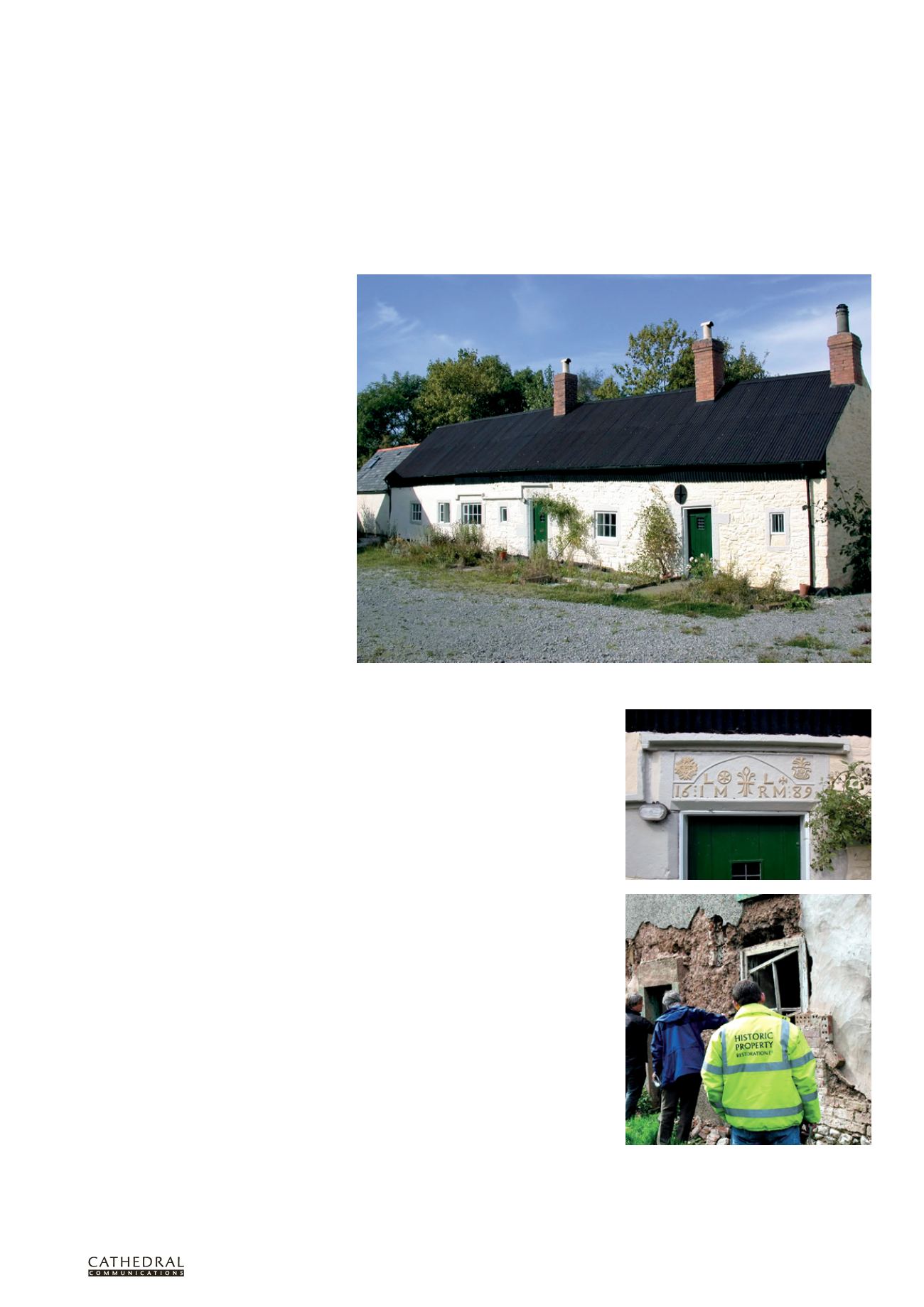

Cottage at Castletown, Cumbria: the cement render

fell away to reveal a waterlogged clay wall. After a

week this had dried out completely. (Photo: Heritage

Skills Initiative)