7 6

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

3.1

STRUCTURE & FABRIC :

ROOFING

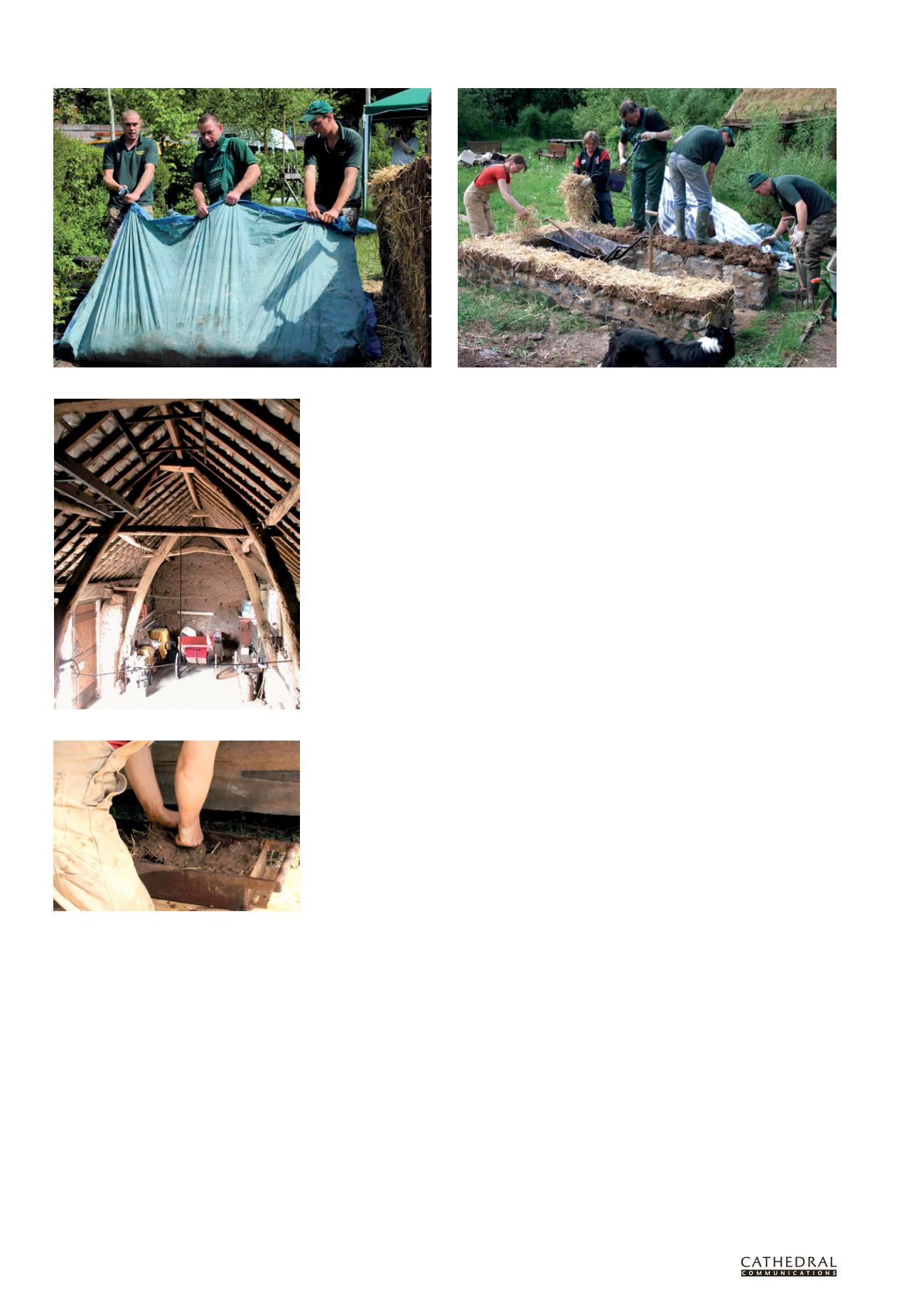

Treading in the clay, levelling the sides and laying the straw course

main ingredient is straw. Both wheat and

barley straw were used and approximately 25kg

is used per cubic metre of subsoil. Water must

be added to the mix to allow the clay to break

down and coat the aggregate and straw. This

is done by treading the mixture and breaking

up all of the subsoil until there is no dry

material left. The amount of water is critical

because too much will make the mixture

very sloppy and impossible to apply. Once

mixed, it must be turned and trodden again

(top left). The process may have to be repeated

several times to get the right consistency,

which can be an arduous task. Mechanical

means (a JCB or a tractor with a bucket to

turn the mix) can speed up production.

Part of the training involved making clay

blocks (left) which would be used in the repair

of clay dabbins as well as their construction.

The same dabbin mixture is used to make the

blocks using a timber or metal mould made

up to an appropriate and convenient size for

the task. The blocks need to be laid out to dry

under cover and turned after three weeks.

The longer they are left to dry the better.

The process of building the clay wall is

straightforward but needs skill and judgement

in laying the material, treading it down firmly

but without squeezing it off the wall, and

protecting the edges and corners to ensure

that they remain vertical and solid. Beating

the sides can maintain a vertical wall and

where there are any bulges these can usually be

trimmed off at the end of the day (above right).

The process continues until the required

eaves height is reached and the gables can then

be constructed. In this trial the upper half of

the building and the gables were completed in

clay block with the purlins and ridge built into

the clay wall (facing page, top). The walls were

plastered with an earth render and a thatched

roof was added consisting of turf laid as an

undercoat onto pole rafters and heather thatch

laid on top.

REPAIRS

Deterioration can be caused by damp, water

penetration, cement renders and defective

rainwater goods as mentioned above. Other

common defects include cracks which

extend through the clay wall, and hollows

and cavities such as rat runs. Sections of clay

Cruck barn at Drumburgh, Cumbria

As a result of the survey, English Heritage

was aware of the situation and eventually

agreed to fund a programme – the Clay

Dabbins Project – to train contractors in

clay building techniques and also to engage

with clay dabbin owners to make them aware

of the importance of their buildings and to

reverse the widely held impression that these

buildings were damp, dangerous and not worth

retaining. This view had been generated by

many builders who, when faced with questions

about how to repair a clay wall or get rid of

its damp problems which they were unable to

answer, suggested that nothing could be done

and that the buildings should be demolished

and replaced with breeze block. The damp

problems, needless to say, were usually

created by previous builders who had applied

cement render to ‘solve’ a damp problem.

The partners in the Clay Dabbins Project,

which was initiated in 2009, were English

Heritage, the North of England Civic Trust,

Grampus Heritage and Training Ltd, and

Carlisle City Council. The main aim was to

give training to builders to enable them to

tackle clay dabbin construction and repair.

Further funding was obtained the following

year from the Heritage Skills Initiative

which enabled the project to expand to

include professionals and the general public.

A programme was devised to train builders

on a course that was centred on constructing

a small bothy (a simple, one-room structure)

using the clay dabbin tradition. This would

encompass all of the essentials for dealing with

clay dabbins of any size or scale. It would also

see the construction of the first clay dabbin for

more than a century.

The training was provided by Becky

Little and Alison Davie from Fife, whose

firm, Little and Davie Construction, has

had a great deal of involvement in the

repair and restoration of earth buildings,

including one on the Solway Plain.

The traditional communal process of clay

dabbin construction was to mix clay or mud

and straw with the addition of water to bind

the two. The straw is pressed into the wet clay

by treading it (cattle were sometimes used to

do this). Once thoroughly mixed, this material

can be carried to the previously prepared

plinth and it is then laid in thin layers, each

separated by a thin layer of straw. The straw

helps the drying process and allows the next

layer to be started immediately, without having

to wait for any drying out. This is in contrast

to other regions where the lifts (layers) are up

to three feet deep and need up to a week before

the wall is dry enough for a builder to stand on

top and lay the next lift.

The clay used was whatever was

available locally and it can vary enormously

in composition (from having considerable

proportions of aggregate in the clay to almost

all silt). A serviceable mixture today could

contain (by weight) 30 per cent stone/gravel

(5–40mm), 30 per cent coarse and fine sand,

15 per cent silt and 25 per cent clay. The other

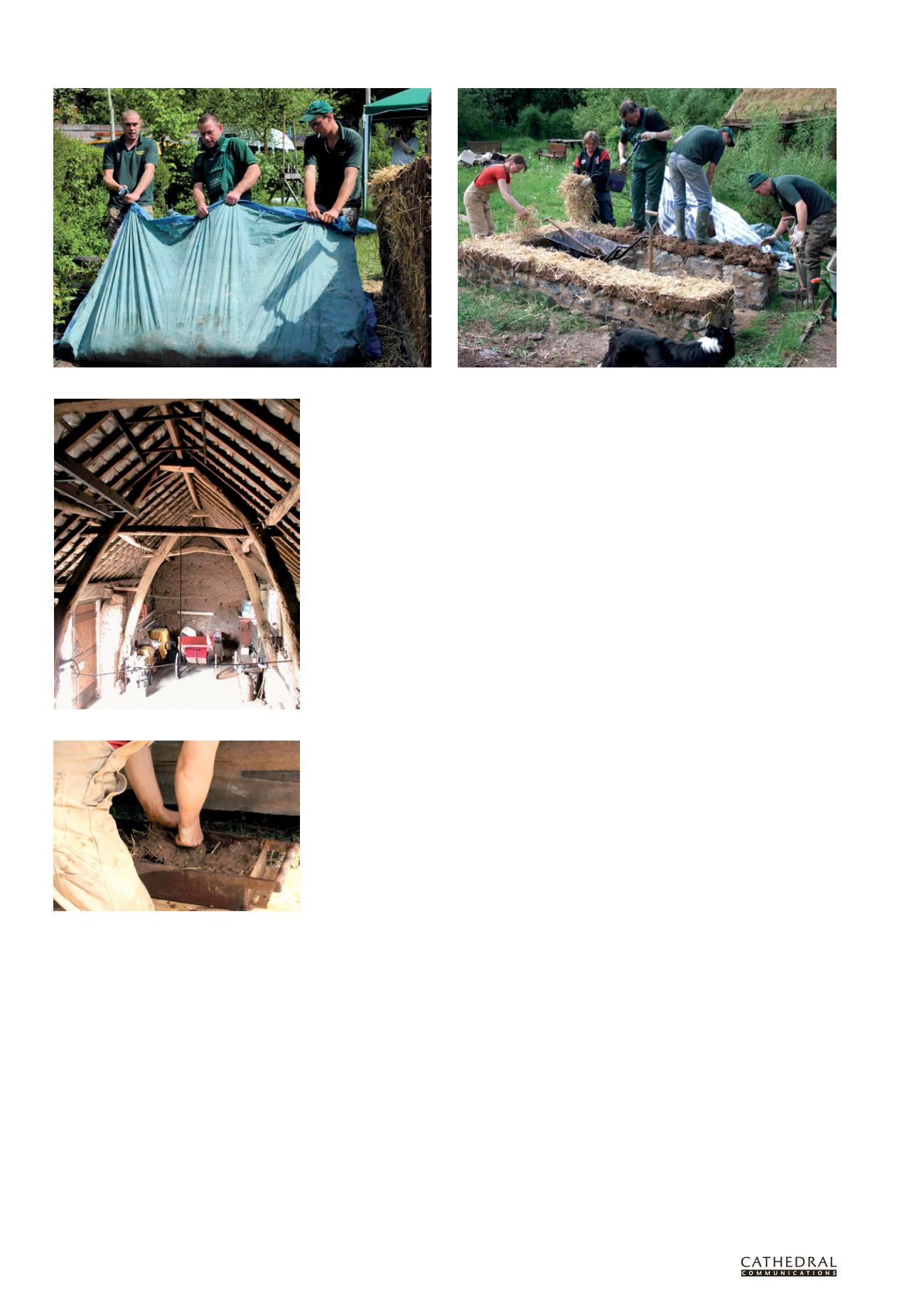

Turning the mix (Photo: Heritage Skills Initiative)

When making clay blocks the mixture must be well

compressed into the mould