26

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

24

TH ANNUAL EDITION

on the cross washing away the sin of

mankind. It is unsurprising that Puritan

protestants of the 16th and 17th century

regarded such objects as idols. The

pelican lectern at Norwich was buried,

probably to prevent its destruction.

By the late 16th century, few church

wardens regarded the opulence of the

lectern as a fitting support for the Bible.

Of the 100 or so brass lecterns

mentioned in inventories in 1536, less

than half survive today, and many

probably ended up in the melting

pot. Many of these pre-Reformation

lecterns had only recently arrived in

the churches. At Peterborough the

inscriptions on the lectern presented by

the Abbot William Ramsey and Prior

John Malden are illegible today, but they

were recorded in the past and date the

lectern to between 1471 and 1496. At

Wiggenhall St Mary Magdalen, Norfolk

the engravings can be deciphered as

reading

orate pro anima fratris Robti

Bernard gardiani Walsingham anno

Domini 1518

. The one now at Southwell

Minster, recovered from the lake at

Newstead Abbey, is dated 1503 and the

lectern at Lowestoft is dated 1504. Among

the later pre-Reformation lecterns is the

one in Woolpit which dates from 1520.

No attempt was made by the Tudors

to strip church interiors of these objects

of idolatry on a national scale. However,

many church wardens chose to replace

the lavish lectern with a bookstand made

of a humbler material like wood. At Long

Melford, Suffolk, the medieval Rood

Cross was used to fabricate a support for

the English Bible.

The lecterns which survived the big

sell-off during the 16th century became

objects of a witch hunt in the years of

the Civil War and the Commonwealth.

A Puritan rage tried to cleanse the

nation of its blasphemous bookrests,

an unsurpassed iconoclasm smashing

to pieces centuries of religious heritage.

In 1642 troops under the command

of Colonel Sandys destroyed the early

16th-century lectern inside Canterbury

Cathedral. Not far from the bridge at

Cropredy, site of a Civil War battle of

1644, a brass eagle lectern was retrieved

from the river and now sits in the local

church. Whether it was hidden from

Parliamentary troops before the battle

or thrown in by Puritans is unknown.

Similar stories are told across the country,

from Bovey Tracy in Devon to Oundle in

Northamptonshire. Many lecterns were

not recovered until the early 19th century,

an unexpected resurrection after being

buried for centuries.

At Canterbury Cathedral a new

beginning was marked when a brass

eagle lectern was placed in the choir

during the Restoration, made by William

Borroughes of London in 1662. Once

again the brass eagle lectern adorned an

English ecclesiastical space, translated

to the new function and location for

an Anglican liturgy, supporting the

Bible in the English language and

placed in the body of the church.

Further Information

M van der Meulen,

Brass Eagle Lecterns

in England

, Amberley Books,

forthcoming 2017

CC Oman, ‘Medieval Brass Lecterns in

England’,

Archaeological Journal

,

Vol 87, 1930

CC Oman, ‘English Brass Lecterns

from the Seventeenth and

Eighteenth Centuries’,

Archaeological

Journal

, Vol 88, 1931

T Rehren and M Martinón-Torres,

‘Naturam Ars Imitata: European

Brassmaking between Craft and

Science’,

Archaeology, History and

Science: Integrating Approaches

to Ancient Materials

, Left Coast

Press, California, 2008

M de Ruette, ‘Les Lutrins “Anglais”:

Considerations Techniques’,

Actes.

Congrès de la Fédération des

Cercles d’Archéologie et d’Histoire

de Belgique

, Vol 49, 1991

MARCUS VAN DER MEULEN

(marcusvandermeulen@outlook.be)

researches the reactivation of churches as

a preservation strategy and studies church

interiors. He is a member of the Centro Studi

Ghirardacci, Bologna University and a member

of the Future for Religious Heritage Network

Committee. His book

The Brass Eagle Lecterns

of England

will be published later this year.

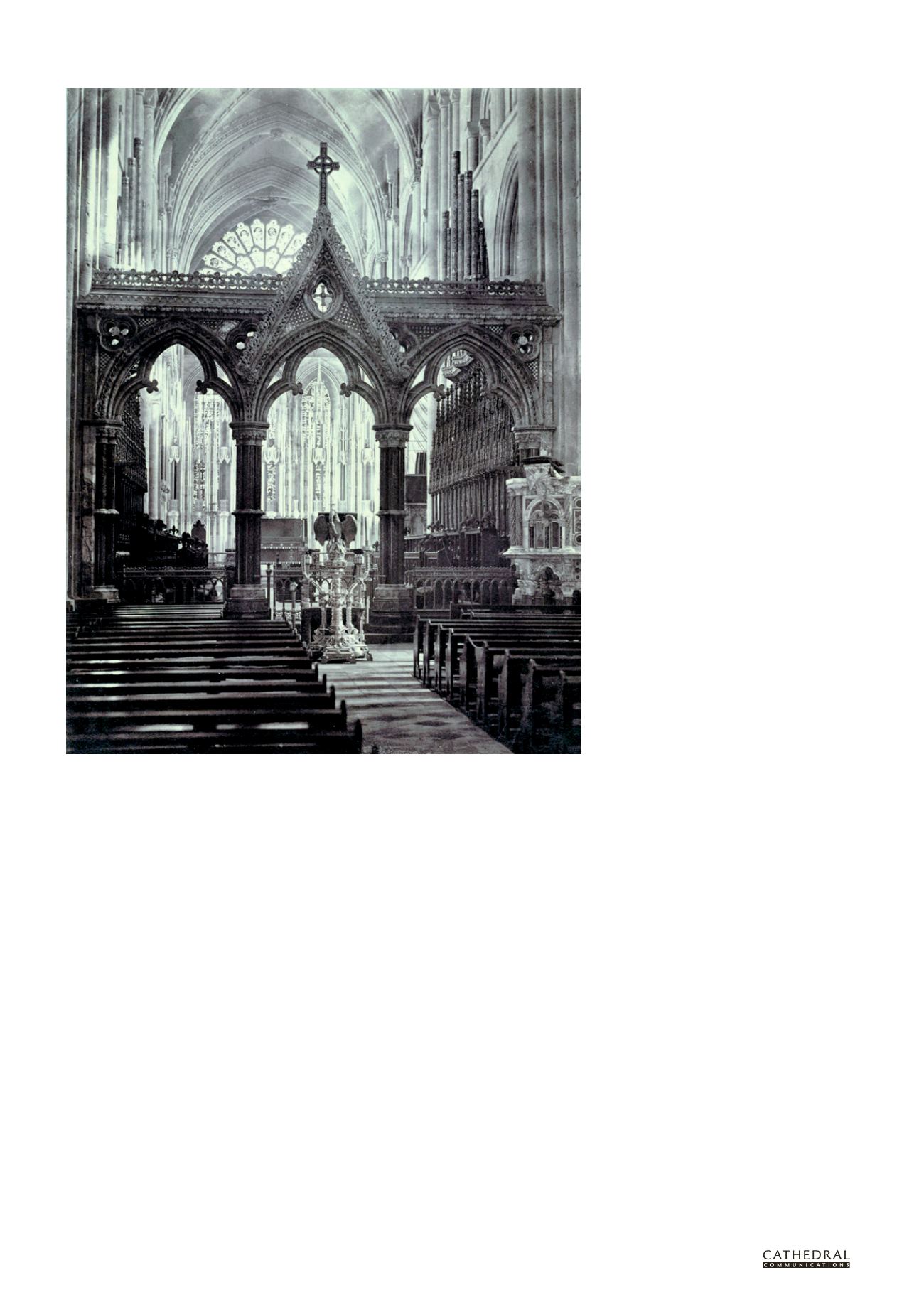

Interior of Durham Cathedral looking towards the choir in the late 19th century, with Scott and Skidmore’s

pelican lectern in the location for which it was conceived (Source: AD White Architectural Photographs

Collection, 15/5/3090.01048, Cornell University Library)