BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

24

TH ANNUAL EDITION

25

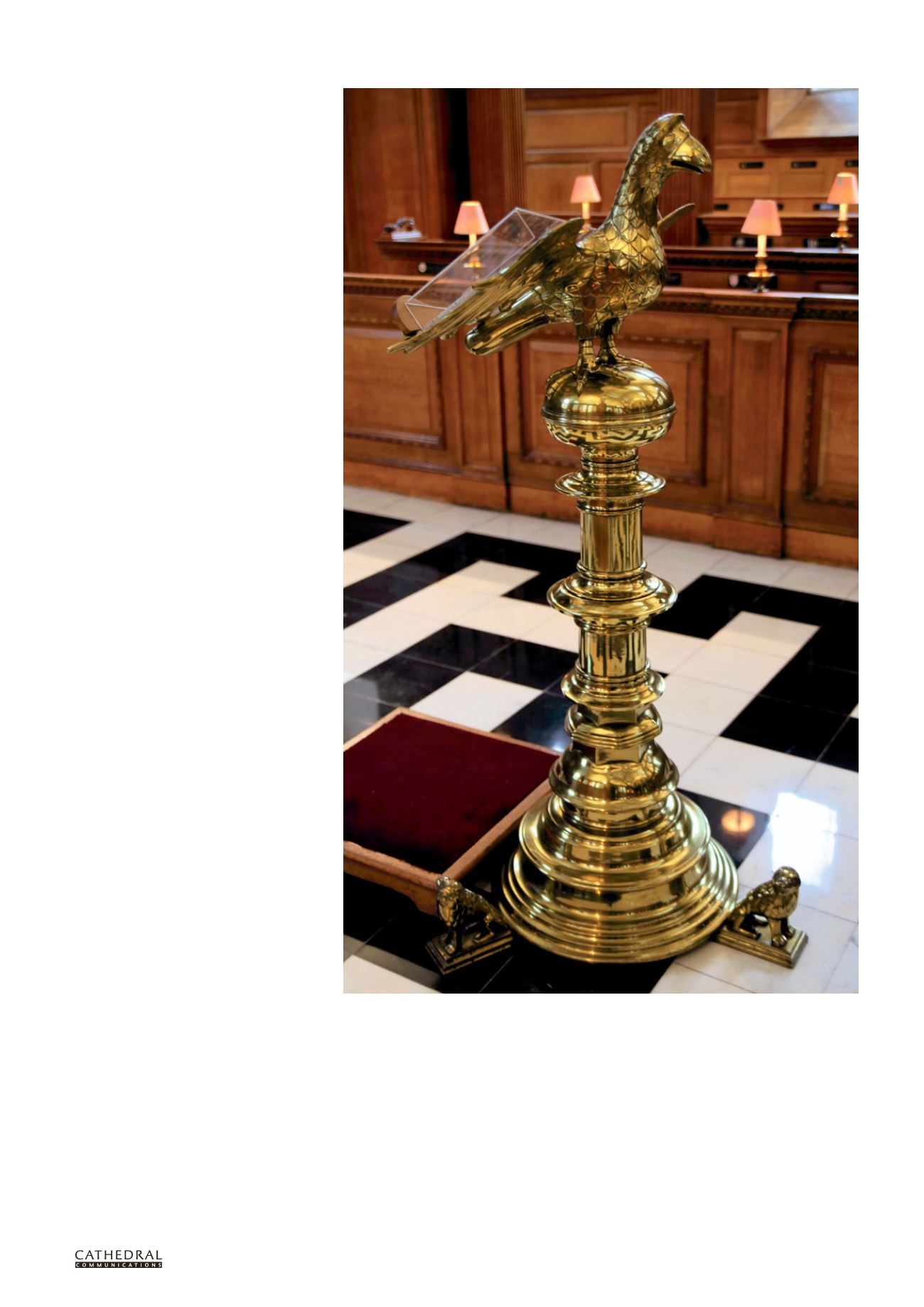

In 1539 the Great Bible was presented

and a copy had to be displayed for all to

consult. Freestanding bookstands like

the brass eagle lectern already present in

some houses of worship could fulfil the

task perfectly. In the Church of St Petrock,

Exeter, the lectern was placed in ‘the

body of the church, to set the Bible on’.

The inventory of 1554 describes ‘an egle

of latten whiche ys to leye the Bible on’ in

the church of Havering, Greater London.

Of all the brass eagle lecterns in England

dating from before the Gothic Revival

of the 19th century and the industrial

output that followed, a surprisingly large

number can be dated to between 1470 and

1530. Only one is earlier and can truly be

called medieval, that of Holy Rood Abbey,

Southampton, today at St Michael’s

Church. From the 18th century two

survive, one at Brasenose College, Oxford,

the other at St Paul’s Cathedral. Less than

a dozen were made in the 17th century,

and none during the Commonwealth.

Yet a staggering 40 or so survive from

the relatively short period between the

end of the Wars of the Roses and the

beginning of the English Reformation.

THE DECLINE

The consequences for the church interior

could not have been anticipated when

Henry VIII broke away from Rome in 1534.

In the process the liturgy was reformed,

heralding a rising influence of protestant

attitudes towards idolatry, with radical

implications for the church interior.

At Westminster Abbey the sale of

two brass lecterns was ordered by the

chapter in 1549 as they were ‘monuments

to idolatry and superstition’. The

supposed profanity can be explained

by the iconographical connotations of

the eagle. It is a symbol of St John the

Evangelist, whose Gospel starts with the

words

In principio erat Verbum

(‘In the

beginning was the Word’), so there was

a symbolic connection between the

eagle and the Bible which rested on its

wings – the word of God. The eagle is

one of the four animals of Ezekiel, a

tetramorph which is completed by the

bull for Luke, the lion for Mark and an

angel for Matthew. Depictions based

on texts in the Bible were accepted

by many early protestants. One of the

earliest Lutheran church interiors,

the chapel at Wilhelmsburg Castle

in Schmalkanden, features a curious

altar-cum-font supported by all four

creatures from Ezekiel’s vision.

Yet another connotation of the eagle

could be regarded as outright blasphemy.

The

Physiologus

, a medieval encyclopedia

describing the earth as an allegory of

Brass eagle lectern c1500 at Wren’s Church of St Bride, Fleet Street, London (Photo: Marcus van der Meulen)

heaven, regards the eagle as the King

of Heaven. In the 13th century Thomas

Aquinas wrote ‘as an Eagle He [Christ]

ascended aloft into heaven’. As an allegory

for Christ, the brass eagle lectern was the

epitome of the idolatry which Puritans

wished to excise.

The

Physiologus

also provides an

explanation for the pelican’s significance,

claiming that the bird would pierce its

own breast to feed or revive its brood.

In one of his Eucharistic hymns for the

Feast of Corpus Christi (1264) Thomas

Aquinas made the connection with Christ

even clearer:

Pie Pellicane, Iesu Domine.

Me immundum mundo tua sanguine

(‘Pious pelican, Lord Jesus, cleanse

me, impure one, in your blood’). The

pelican thus provided the church with a

vibrant allegory for Christ, his sacrifice