4

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

24

TH ANNUAL EDITION

from toddlers upwards, reaching

many who lack confidence to

find self-worth elsewhere.

The practical contribution they make to

their communities is huge but we would

be wrong to ignore their deeper symbolic

significance. As Sarah Coakley (see

Further Information) observes:

‘The Church is not a building.’ That

is most certainly true. But buildings

in which ‘prayer has been valid’

are more like people than stone

or brick, because of their vibrant

association with the folk we and

others have loved. They are not so

much haunted as ‘thin’ to another

world in which past, present and

future converge. And when, as in

the parish system in England, each

such building holds the memories

of a particular geographical

community, it is well to be aware

of its remaining symbolic power

– even if it now seems neglected,

under-used or actively vandalised.

They are the repositories of the stories of

communities, their parishes. The notion

of ‘parish’, derives from the integration of

the Christian church into the civic life of

the Roman Empire. The English parish

system is very ancient and its churches

are valued by their parishioners but by

many others besides. Writing in

The

Shell Guide to England’s Parish Churches

,

Robert Harbison in 1992 described what

he called a ‘vast avalanche’ of books on

England’s parish churches. These are

guides for church-spotters, of which

John Betjeman’s

English Parish Churches

(1958) is still the paradigm. They often

comment on the broader place of the

parish church in the English natural

and social landscape though the latter

is only now being investigated more

thoroughly (see Further Information,

Davison and Millbank, Rumsey).

There is much to celebrate in terms of

the health of these wonderful buildings.

A glance at 18th-century prints makes

clear the parlous state into which the

majority had fallen at that time. Following

all the restoration and building work of

the 19th century, war consumed much

energy during the first half of the 20th

century. Fortunately, huge amounts of

money have been spent on them in the

last generation. Our churches are arguably

in a better state as far as their fabric is

concerned than has ever been the case.

What of the future? The Church

of England is the custodian of these

buildings which are everyone’s heritage

and maintaining them is an increasing

burden. In financial terms we are the least

established church in Western Europe:

before the recent

Roof Repair Fund

and

First World War Centenary Cathedrals

Repair Fund

there had been no direct

government funding for the repair of

parish churches. In most other countries

there is either a church tax or the state

is responsible for the maintenance of

historic churches.

Our approach has its advantages:

most of our churches feel ‘loved’ in a way

that, for example, French churches do

not. There is, however, a challenge and,

with that in mind, I was asked by the

Archbishops’ Council of the Church of

England to chair a group charged with

undertaking a review of the Church

of England’s stewardship of its church

buildings.

In September 2015 the group

produced its report, which was well

received by the Archbishops’ Council and

Church Commissioners. It disappointed

some who feel that church buildings

are a millstone around the neck of the

Church of England. As Giles Fraser put

it in

The Guardian

, they are ‘sapping the

energy of our wider social and religious

mission, and transforming the church into

a buildings department of the heritage

industry’. We disagree. We feel that to

take a Beeching type axe to the churches

of this land would be to do a disservice

both to the church and to the nation. We

feel this to be the case precisely because

they are more than historic monuments

and because they are still, wonderfully,

being used for the purpose for which they

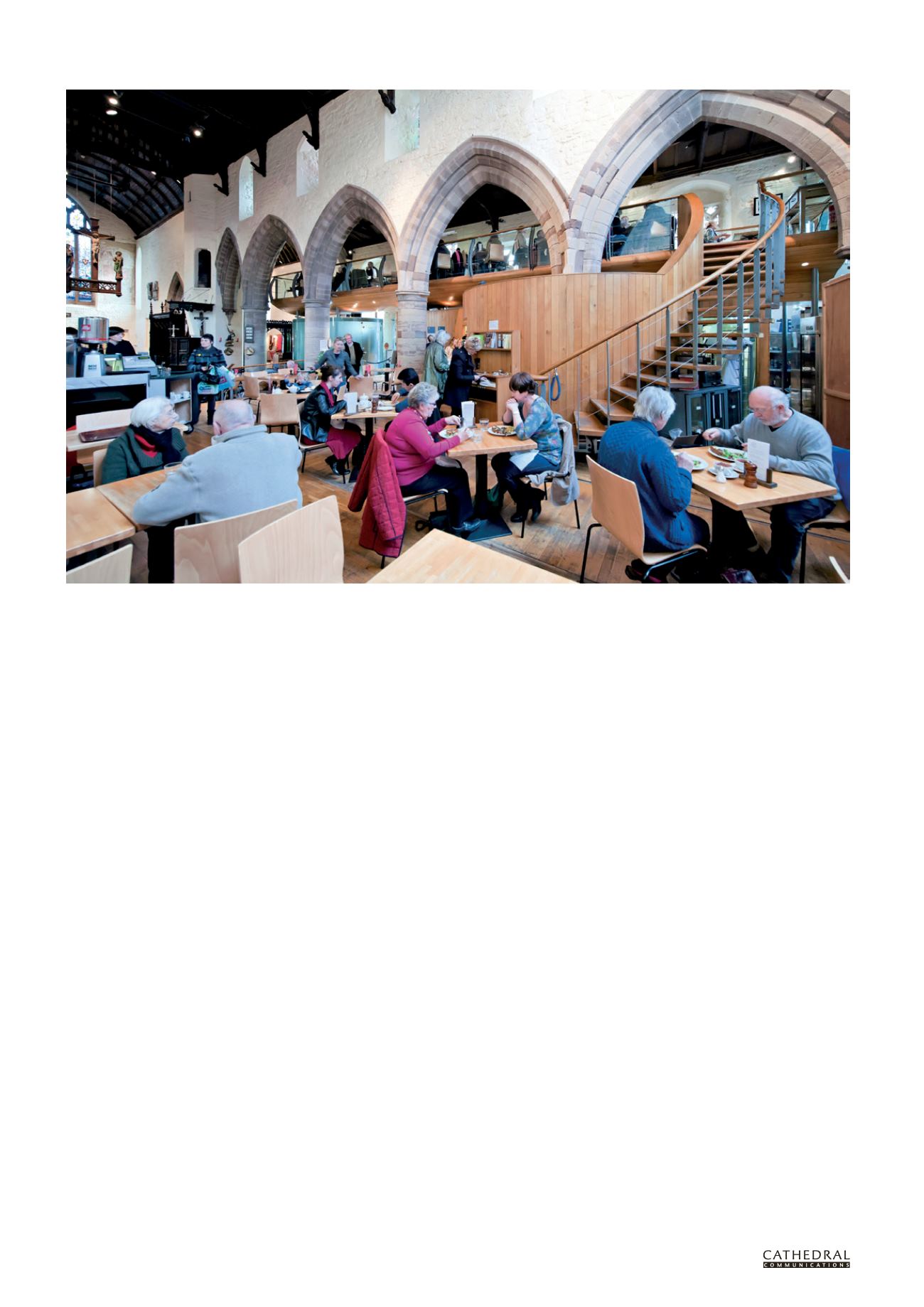

Community centre and café at All Saints, Hereford (Photo: Alastair Lever/Archbishops’ Council)