6

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

24

TH ANNUAL EDITION

except when open for worship and are

increasingly marginal to the life of the

communities they exist to serve. They

remain oases of calm, but unavailable.

The picture is far from hopeless. We

commend a rising wave of imaginative

adaptation of church buildings for

community use which has breathed new

life into them. An increasing number, like

St Giles’s, Langford, near Chelmsford,

now house a village shop or post office.

Many, like St Stephen’s in Redditch, are

home to a food bank. Some, like St Mary’s

in Ashford, Kent, have been reordered

to become community arts venues as

well as places of worship. New and ever

more imaginative schemes are constantly

springing up: All Saints in Murston,

Sittingbourne, is the first to host a

community bank.

The examples are myriad and should

serve as an inspiration. If church buildings

are to succeed, their adaptation and

alteration must be welcomed. It should

be sensitive to their heritage and to their

primary purpose as places of worship of

Almighty God, but it should emphatically

not make preserving the status quo a

primary aim. Proper conservation is about

managing change not preventing it. A

case in point is pews, very often a quite

recent addition to churches. Removing

them enables a flexibility in the use of the

building which would have been possible

in the past but which pews prevent.

Only if such flexibility is not merely

allowed but welcomed and encouraged

will churches remain healthy and vibrant

and continue to be used for their original

purpose. The alternative will be for them

to close and that, as I have argued above,

would be a great loss. While our report

acknowledges that some churches will

need to be closed, it also advocates a

change in the mood music: with a positive

mind-set we can see their true potential,

rather than simply characterising them as

a ‘burden’. In

A Little History of the English

Country Church

(2007), Sir Roy Strong

advocates ‘giving the church building

back to the local community, albeit with

safeguards for worship. Change has

been the lifeblood of the country church

through the ages. Adaptation will be more

important than preservation’. Amen to

that, I say.

Further Information

Church Buildings Review Group,

Report

of the Church Buildings Review Group

,

2015

(http://bc-url.com/churchreview)S Coakley in S Wells and S Coakley,

Praying for England: Priestly Presence

in Contemporary Culture

, Continuum,

London, 2008

A Davison and A Millbank,

For the Parish

,

SCM, London, 2010

S Hill, ‘At the Still Point of the Turning

World: Cathedrals Experienced’ in

S Platten and C Lewis (eds),

Flagships of

the Spirit: Cathedrals in Society

, Darton,

Longman and Todd, London, 1998

I Poulios,

The Past in the Present:

A Living Heritage Approach

,

Ubiquity Press, London, 2014

A Rumsey,

Parish: An Anglican Theology

of Place

, Forthcoming

R Strong,

A Little History of the English

Country Church

, Jonathan Cape,

London, 2007

N Walter and A Mottram,

Buildings

for Mission

, Canterbury Press,

Norwich, 2015

JOHN INGE

PhD is the 113th Bishop of

Worcester and lead bishop on Cathedrals and

Church Buildings for the Church of England.

His book,

A Christian Theology of Place

, was

shortlisted for the Michael Ramsey Prize for

Theological Writing.

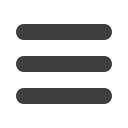

Wymondham Abbey, Norfolk: the building’s visible history of change and adaptation is part of its beauty (Photo: Barry Cawston/Archbishops’ Council)

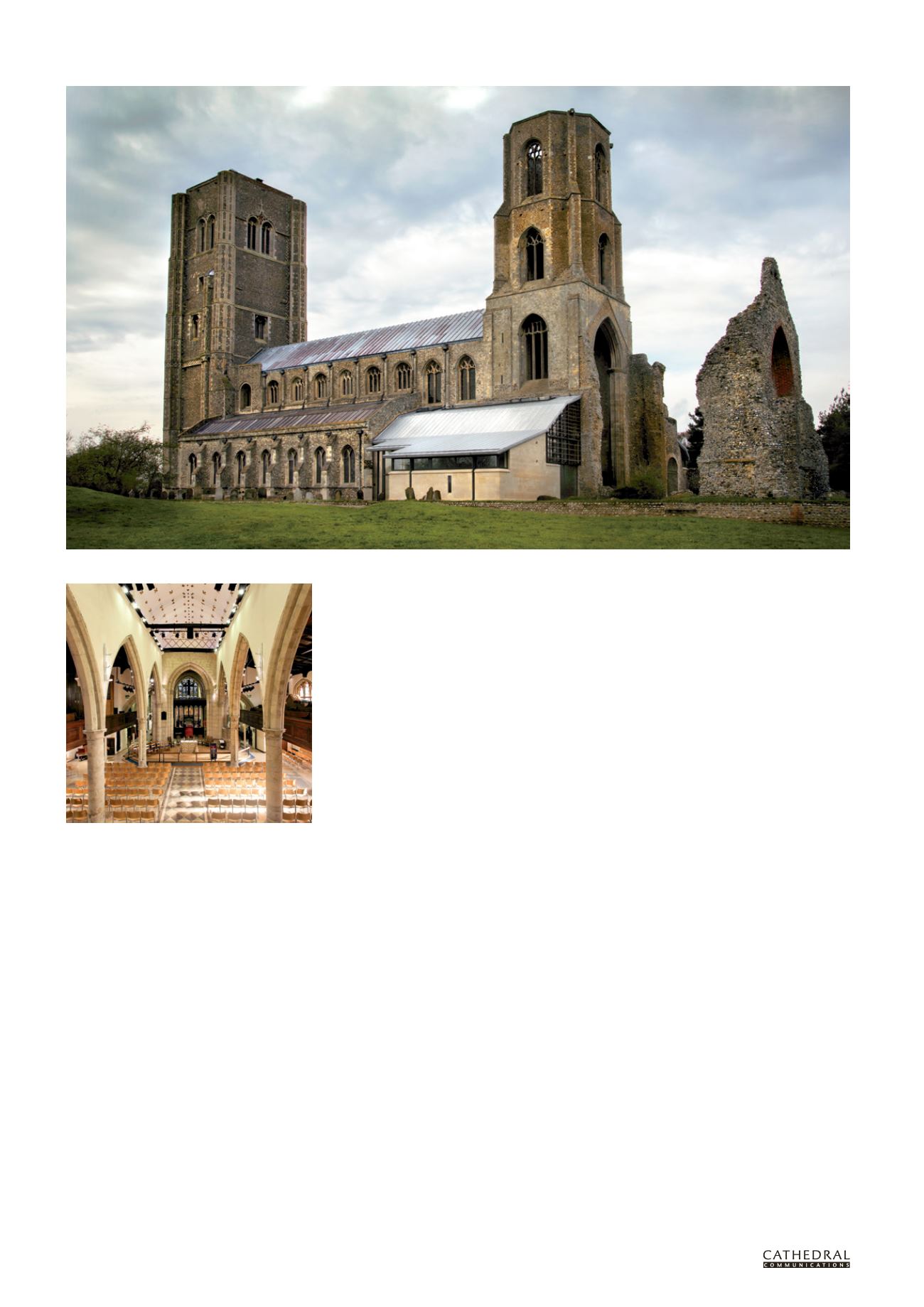

St Mary the Virgin, Ashford, Kent: reordering for

community centre with removal of pews (Photo: Lee

Evans Partnership)