BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

24

TH ANNUAL EDITION

5

were built. They offer something unique

and hard to define in addition to their

architectural glory.

Perhaps that additional something

is better captured by novelists and

poets than by architects, theologians

and historians. What the novelist Susan

Hill writes of cathedrals (see Further

Information), could be said of parish

churches: ‘Where else in the heart of a city

is such a place, where the sense of all past,

all present, is distilled into the eternal

moment at the still point of the turning

world?’ She asks another rhetorical

question which amplifies the point:

But surely there are other places

that will serve the purpose? To

which people may come freely, to

be alone among others? To pray, to

reflect, to plead, gather strength,

rest, summon up courage, to

listen to solemn words. What are

these other places? To which the

pilgrim or the traveller, the seeker,

the refugee, the petitioner or the

thanksgiver may quietly come,

anonymously, perhaps, without fear

of comment or remark, question

or disturbance... To think of the

world without these cathedrals,

without all cathedrals, is like a

bereavement. It is painful. The

loss of the buildings themselves,

the grandeur, the beauty, is

unimaginable – the mind veers

away from it. But think of the

world without the great palaces.

Surely that is the same? We know,

deeply, instinctively, that it is not.

Destroy all the churches then.

Is not that the same? We know

that it is more. And that it is not

merely a question of thunderbolts.

There is indeed more, much more. That is

surely because these buildings are ‘living’.

This makes them particularly precious

and, at the same time, something of a

headache as far as their conservation

is concerned. There are those who feel

similarly to William Morris, whose words

are quoted in the SPAB manifesto, who

felt it proper

to resist all tampering with either

the fabric or ornament of the

building as it stands; if it has

become inconvenient for its present

use, to raise another building rather

than alter or enlarge the old one; in

fine to treat our ancient buildings

as monuments of a bygone art,

created by bygone manners, that

modern art cannot meddle with

without destroying.

Morris, of course, was protesting against

Victorian restoration of buildings. We

may feel that restoration to have been

heavy-handed but the fact is that, had it

not taken place, many would have fallen

down and they would not be usable today.

Buildings had, in fact, been significantly

adapted many times over the centuries.

One of their glories is the hotchpotch of

architectural styles they display. These

changes have enabled them to ‘live’, and

to subject them to Morris’s imperative

would be to sign their death warrant. They

would become lifeless museums which,

if listed, could probably not be put to any

alternative use anyway.

How can their health be assured?

The approach of the Church of England

in this regard is different from that

of other denominations. Many of the

free churches are happy to dispose of

old buildings and build anew because

they don’t have a great emphasis on

or regard for heritage or sacred space.

Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic Church

is bound by a ruling dating back to

the Council of Trent that their church

buildings can only be used for worship

and, as such, are less of a problem for

the conservationist. Since Henry VIII

gave us ‘Brexit’ from Rome and its rules,

the Church of England has been free to

re-discover and reintroduce the mixed

economy of medieval Christendom.

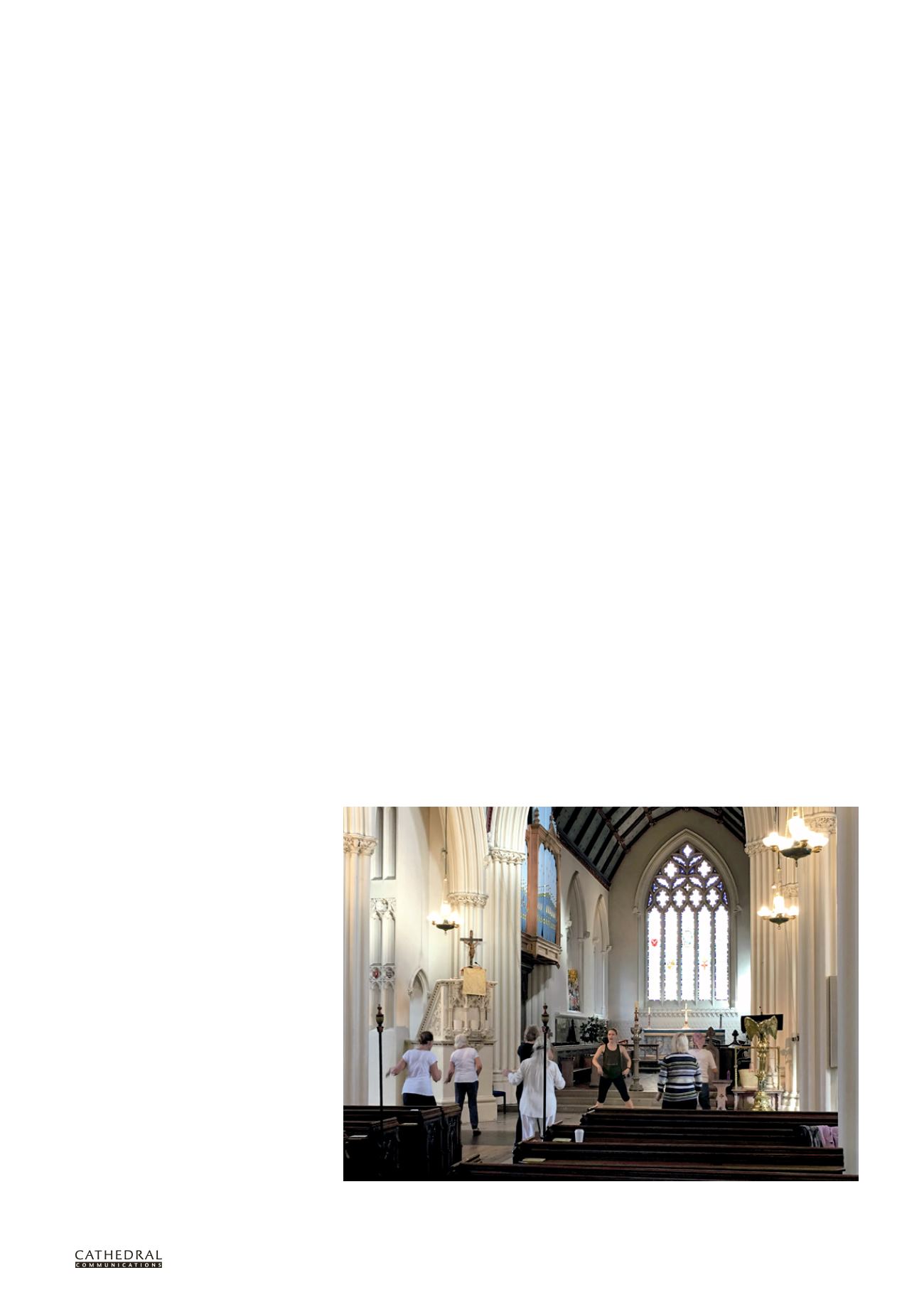

To advocate such a mixed economy

is not to deny the holiness of our

churches. In our report we observe that

‘in Church of England polity some places,

notably churches and graveyards, are

deemed to be “holy” by virtue of their

consecration’. It should be noted that

the word ‘holy’ simply means set apart.

What are churches ‘set apart’ for? They

are set apart to symbolise the Christian

faith. We observe that if they are to

be effective symbols of the Christian

faith we must avoid them becoming

redundant or museums by allowing them

to live and breathe. This will often mean

re-ordering and adapting in a manner

which is sensitive to their heritage but

that will enable the life of contemporary

worshipping Christians and service of

the community (see Further Information,

Walter and Mottram, Poulios).

We argue that one of the reasons

a number of churches have become

more like museums is possibly a lack

of awareness that both parts of Jesus’s

summary of the Commandments have

repercussions for churches, as they do for

disciples. The first purpose of churches, as

with human beings, is to worship God and

churches generally do reasonably well on

the first Great Commandment.

The record is not always so good with

the second, to love our neighbour. As it

applies to churches, it implies that they

should be vibrant centres of service to

the community. Traditionally, churches

were at the heart of the communities

in which they stand, in both a human

and a geographical sense. It is well

known that in the medieval period much

‘secular’ activity would have taken place

within them. Over the years, however, a

pietism crept in which tended to exclude

everything but public worship from

them, all other activity being transferred

to places such as halls and community

centres. Far too many churches remain

locked and stand like mausoleums

St Stephen’s, Rochester Row, London: Zumba class in the nave (Photo: Joseph Friedrich/Archbishops’ Council)