BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

24

TH ANNUAL EDITION

37

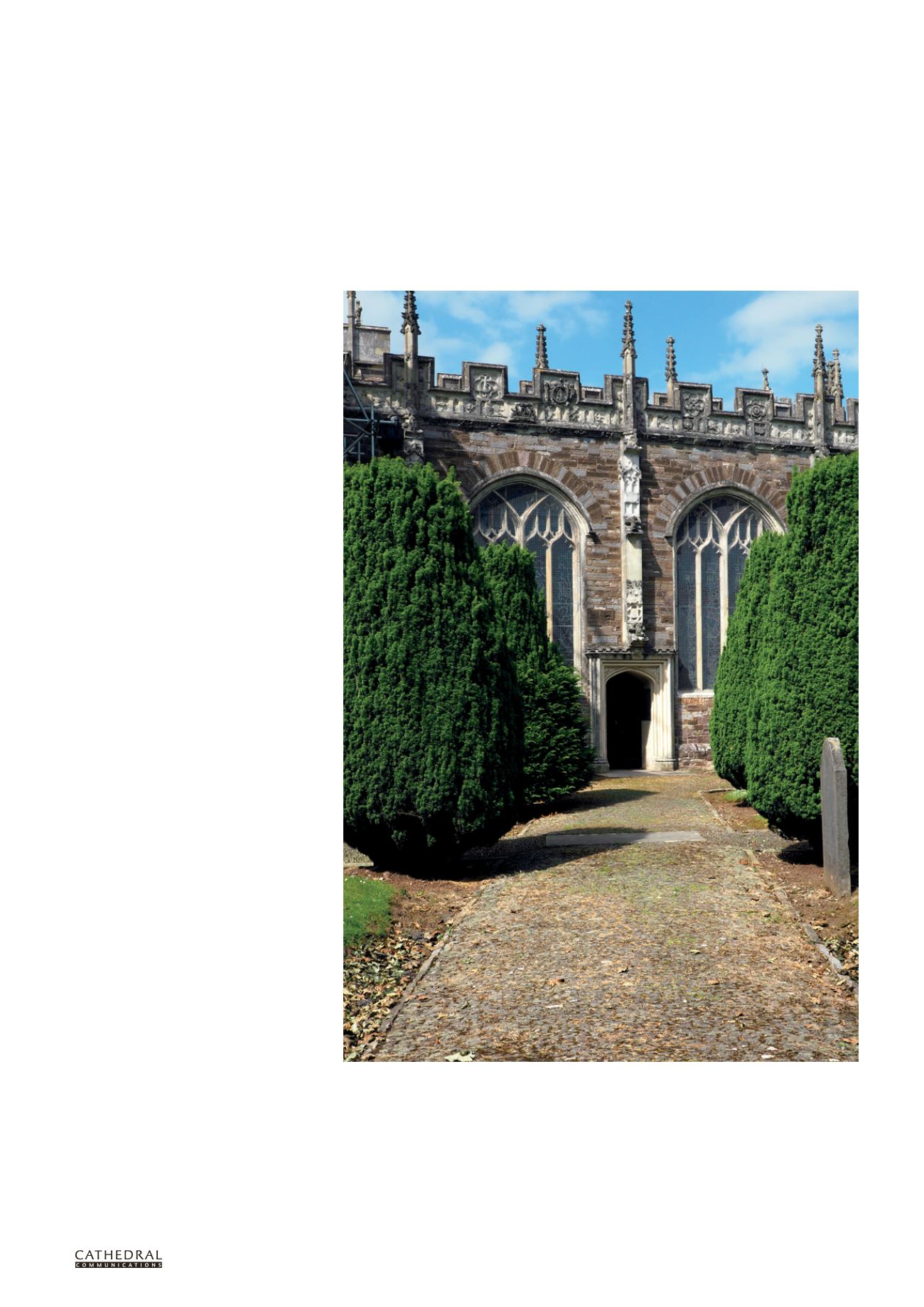

COBBLE REPAIRS

Robin Russell

A

WIDE VARIETY of paving using

locally-available small stones can

be found in churchyards across

the UK. Lying forgotten within their

hallowed grounds, they are often the

last surviving examples of the traditional

surfaces used on neighbouring streets

and paths, so give a valuable insight into

the appearance of the local townscape

before it became covered in tarmac.

Generally, these ‘small-unit’ materials fall

into two categories; cobbles or setts.

Small stones which are cut and

shaped, often quite roughly, are now

known as setts, although many people still

refer to them as cobbles, In areas of the

country where the local stone was easily

split, thin setts are sometimes end-bedded

or ‘pitched’ into the ground. (The term

pitched has nothing to do with the use

of bituminous pitch.) Granite setts are

the most hard-wearing and can be found

furthest from their source as they often

replaced softer local stones following

the development of canals and then the

railways to transport them.

The term ‘cobbles’ describes the

smoother, more rounded stones that

were fashioned by natural erosion or

running water, and were used uncut, as

found. Cobbles were used extensively

to create paths, roads and hardstanding

areas, such as courtyards. Cobble-laying

is a simple but very useful technique, but

unfortunately, as with other trades, the

knowledge of how to do it well has largely

been lost as cheaper and often less-

effective methods have been adopted.

Where cobbled paths have survived,

it is important to carry out repairs using

appropriate materials for both cobbles

and bedding, and to preserve as much

of the original scheme as possible.

At the outset of a project it is therefore

important to identify which areas of the

cobble are to be repaired. Photographs

and sketches should be used to clearly

communicate the nature and scope of the

work to any contractors and controlling

authorities. The key principles are:

Documentation

– record the cobble

before intervention and document

the intervention itself so that future

conservation work is well informed

Minimal intervention

– retain the maximum

amount of historic cobble and repair

rather than replace wherever possible

Reversibility

– ensure that alterations

and additions to cobbled areas can

be undone without harm

Like-for-like

– wherever possible,

match materials and techniques to

the existing work

Tightly packed flat-topped cobbles bound by small kerb stones provide a relatively even surface at St Peter's,

Tiverton, Devon